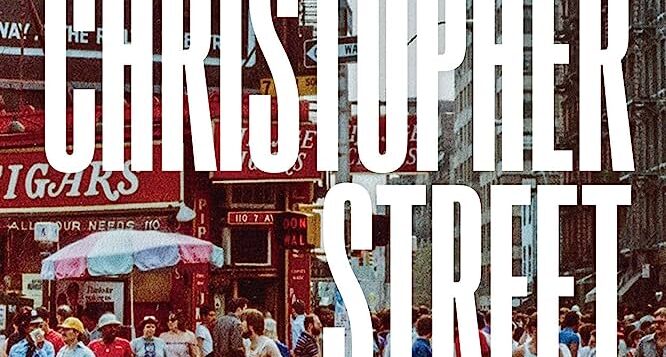

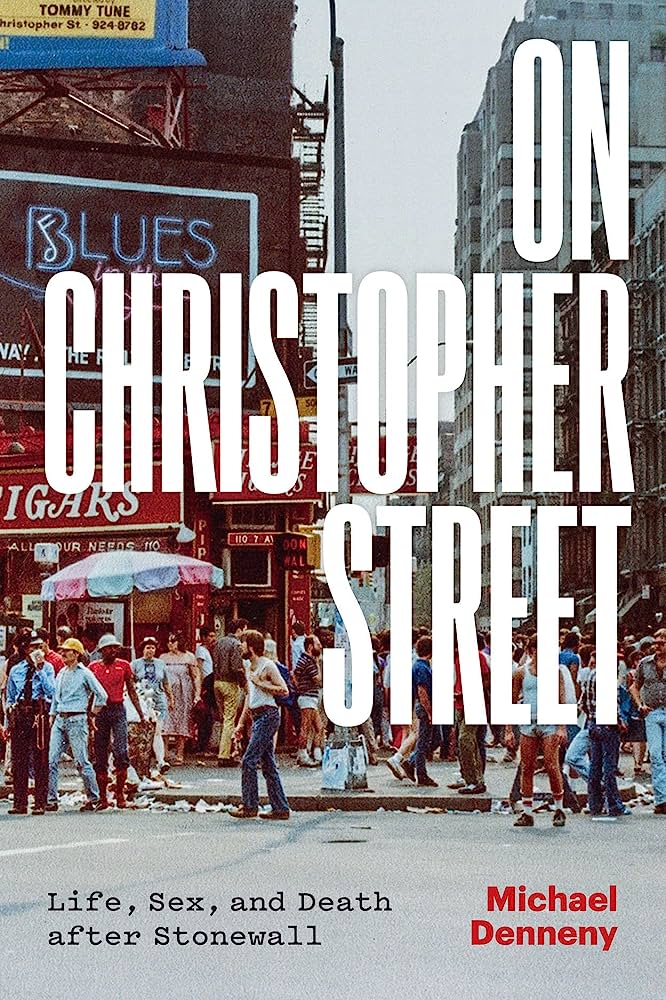

ON CHRISTOPHER STREET

ON CHRISTOPHER STREET

Life, Sex, and Death after Stonewall

by Michael Denneny

U. of Chicago Press. 360 pages, $22.50

Editor’s Note: The late Michael Denneny, author of the book under review, is memorialized in this issue. This review was written prior to his death on April 15th.

IN MY COPY of Lovers, Michael Denneny’s account of a love affair published in 1978, the author wrote: “I wish you would move to Manhattan—then we’d be able to continue the conversation and I’d learn something (and you, of course, would learn a lot).” He had just worked with me on my book, The Homosexualization of America, but I didn’t move to Manhattan, and we lost touch over the intervening decades.

Now a collection of Denneny’s articles has come out, spanning his time as a pioneering book editor at St. Martin’s Press, a founder of the magazine Christopher Street, and a central figure in the establishment of gay literature in the U.S. As a student at the University of Chicago, he had become a follower of Hannah Arendt, whose influence occasionally flashes across these pages. Arendt, a refugee from Nazi Germany, became a central figure in American intellectual life after she published Eichmann in Jerusalem in 1963, where she used the phrase “the banality of evil.”

In the late 1970s, Denneny started work at St. Martin’s Press, whose director, Tom McCormack, was open to publishing gay books. Denneny edited a number of distinguished authors—Ntozake Shange, Buckminster Fuller—but his main contribution was to acquire, discover, and nurture a library of gay, and a few lesbian, authors. The list of books he brought out under the Stonewall Inn imprint, which he founded, runs to two pages, including such important books as Edmund White’s Nocturnes for the King of Naples (1978), Ethan Mordden’s Buddies (1986), Randy Shilts’ And the Band Played On (1987), and Larry Kramer’s Reports from the Holocaust (1994).

In the preface to On Christopher Street, Denneny muses on the reasons for assembling writings that often reflect immediate concerns, largely forgotten by his own generation and ancient history to younger readers. He acknowledges that contemporary readers might find some of the book irrelevant, but his aim is “to show what the unfolding of gay liberation was like for one person, in specific situations and over time.”

The pieces range from political analysis through a series of eulogies for friends and writers who died of AIDS, lightened by such diversions as recipes for an instant dinner party. At moments, as in the description of gym culture in the early days of the epidemic, the pieces rise above the immediate polemics of the time. Many of these articles first appeared in Christopher Street. In an appendix, he recalls that the magazine was “an attempt to more or less do a gay version of the New Yorker.” I remember putting this statement to Gore Vidal, whose response was that he thought The New Yorker already was just that, a gay version of itself. The year was 1977.

For our generation, these were times of jubilation and despair, and Denneny’s collection reminds us of both. In this sense, On Christopher Street can be seen as an archival work, valuable for the historical record it provides, though not without its conspicuous gaps. There is some powerful writing from the early horrors of the AIDS epidemic, but there’s no indication of the descent into crazy conspiracy theories that haunted Christopher Street’s sibling publication The New York Native.

There’s a breathtaking audacity in some of these writings, precisely because they’re so personal. As Denneny stresses, this is just one person’s experience of major historical shifts that were taking place in the LGBT world, but Denneny himself was also an important figure in those shifts, albeit in a particular slice of this world, that of mostly white, mostly male, gay publishing.

A few women did write for Christopher Street, but, as Denneny notes, many lesbians were more active in the Women’s Movement, while gay men had no such outlet for political action. More concerning is that the movement Denneny describes was overwhelmingly white, as is the writing he discusses. Looking back at The Christopher Street Reader (1983), in which I am represented, I’m uncomfortable with the limited range of authors. Along with a few others, I reported from abroad, but none of us actually lived in the countries we wrote about.

One of the times that the world outside the U.S. appears in On Christopher Street is in a piece written when the French philosopher Michel Foucault visited New York, and there’s a description of a public discussion between him and sociologist Richard Sennett where, as Denneny writes, “the cultural elite” were present. Foucault’s own attitudes toward homosexuality, and his reluctance to publicly identify as gay, contrast with Denneny’s repeated assertion as to the centrality of Foucault’s gay identity. But while he lavishes praise on Foucault’s work, he avoids what could have been an intellectual challenge, namely pitting his own American defense of identity politics against Foucault’s ambivalence. In a piece written some years later, he acknowledges the difference in their perspectives but doesn’t elaborate.

Gay New York was a very exciting and a very insular society: a mile high and an inch deep. There’s a moment when Denneny recalls a conversation with the film historian and activist Vito Russo, in which they discuss the movement as if it consisted of everyone in their Rolodex. A central piece in the book is titled “Gay Politics and Its Premises,” first published in 1981, which interrogates the concept of a politics based primarily on sexual identity. The debate remains relevant today. While many in our movement applaud every openly queer legislator elected, others, myself included, are more concerned with the policies than the identities of our politicians.

Dennis Altman is a professorial fellow in human security at La Trobe University in Bundoora, Australia.