AS A CLOSETED TEENAGER in the late 1960s, I came across a glossy 50¢ magazine at a Boston newsstand that spoke to me in a coded language I intuitively understood. It was called After Dark and marketed itself as “the national entertainment magazine.” It could just as well have been labeled “the national gay entertainment magazine,” assuming you could connect to its subtext, which wasn’t all that “sub.” If you were gay the magazine practically winked at you. But you could also place it on the family coffee table and, as a friend once remarked: “It’s the perfect magazine when you don’t want to de-gay your apartment.”

After Dark was filled with everything I loved: theater, dance, literature, television, cabaret, visual arts, drag, film, fashion, opera, pop music—and sexy men in various stages of undress. Though it did have occasional features and back-of-the-book reports from around the country, it was decidedly Manhattan-centric. It was chic, hip, fun, and it made you want to book a ticket to gay Gotham.

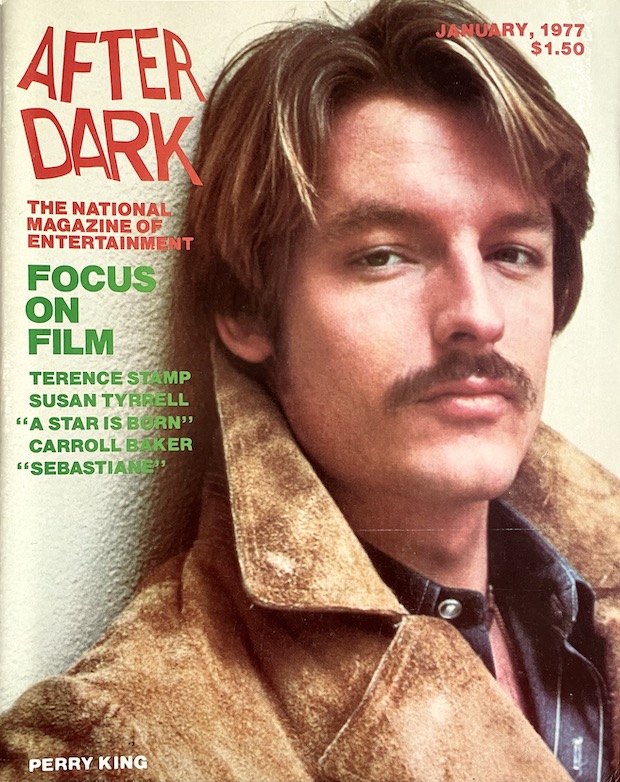

It also tapped into an emerging market for celebrities. Pre-People and Us magazines, this was a monthly that featured covers with stars such as Vanessa Redgrave, Jane Fonda, and Keir Dullea, but it also had a sweet spot for glamour gals from an earlier era, like Mae West, Ginger Rogers, and Veronica Lake. Its entertainment net was cast wide and also featured cultural icons like Maria Callas, Rudolf Nureyev, and Lotte Lenya, plus soon-to-be mono-monikered legends like Dolly, Bette, and Liza. Giving it a sheen of heterosexuality were cover boys like Burt Reynolds, Robert Redford, and Arnold Schwarzenegger, the latter as a glistening bodybuilder and aspiring actor looking coy in his Speedo. (Inside there was a locker room shot with a notorious peek at his penis.)

After Dark emerged from a decade of sexual revolution, artistic experimentation, and a massive generational shift in society, politics, and culture. The magazine launched shortly before Stonewall and printed its last issue just as the AIDS epidemic began. Between those watershed moments was a growing sense of LGBT liberation, joy, and naughtiness in the 169 issues printed between mid-1968 and early 1983. “The post-Stonewall days were a period of enormous flowering of gay male sexuality and of gay and lesbian liberation,” said Eric Marcus, creator of the podcast Making Gay History. “That’s what you saw in the pages of After Dark. It was an opening up that hadn’t been experienced before.”

After Dark emerged from a decade of sexual revolution, artistic experimentation, and a massive generational shift in society, politics, and culture. The magazine launched shortly before Stonewall and printed its last issue just as the AIDS epidemic began. Between those watershed moments was a growing sense of LGBT liberation, joy, and naughtiness in the 169 issues printed between mid-1968 and early 1983. “The post-Stonewall days were a period of enormous flowering of gay male sexuality and of gay and lesbian liberation,” said Eric Marcus, creator of the podcast Making Gay History. “That’s what you saw in the pages of After Dark. It was an opening up that hadn’t been experienced before.”

Inside were stories on gay icons, allies, and cult favorites. The magazine covered both the uptown and downtown scenes, championing experimental art, cutting-edge theater, emerging talents, literary lights, and cultural and liberating signifiers such as Hair, Oh! Calcutta!, The Rocky Picture Horror Show, drag, disco, and Andy Warhol films. It embraced sensuality on any kind of stage, be it Broadway or the Met, but also Vegas clubs, circus tents, ice rinks, and even bullrings.

The magazine’s noted photographer Kenn Duncan created some of its most iconic and tantalizing images, albeit artfully shot in black and white. There were portraits of handsome artists, cute chorus boys, and newbie actors eager for the exposure, and they got it, too, often stripped to the waist—or lower. Fashion models in provocative poses, sculpted ballet stars in their dance belts, and daring downtown artists all gazed knowingly into the lens as if to convey a shared secret with the viewer. They were sexy, yes, but also a little bit innocent, or simply playful. These were fun times, after all, and, as was clear to many, they were gay times, too, in every sense of the word. Actor Harvey Evans (Follies) was on the October 1971 cover dancing naked with only his sailor cap strategically placed in front of him. Years ago, Evans, who died in 2021 at the age of eighty, described his photo shoot to me: “I told my friends that I would be photographed by Kenn Duncan and that I would definitely not take my clothes off. But when I got there, Kenn was so charming and delightfully funny, within a half-hour I had my clothes off. Of course I loved the magazine. Where else could you read about Maureen Stapleton on one page and see a naked person on the next?”

As for the ads in the back of the magazine for mail-order fashions by Ah Men, Parr of Arizona, and International Male, as well as curious places like the Club Baths, well, one could always plead the Playboy magazine defense: “Oh, I just buy it for the articles.”

With the end of the code-conscious Hollywood studio system and the rise of independent filmmakers, movies became more daring and After Dark celebrated those films. If there was a production still from a film that flashed some flesh or a bare-chested hunk, it was in the magazine or on its cover. That included John Phillip Law in Barbarella, Roger Daltrey in Tommy, Casey Donovan/Cal Culver from Boys in the Sand, and Andy Warhol film fave Joe Dallesandro. The magazine also featured large spreads on gay enclaves such as Fire Island, Key West, Provincetown, and the Castro, giving readers a taste of places that men who love men could proudly enjoy.

Founding editor-in-chief William Como, art director Neil Appelbaum, and managing editor Craig Zadan (who would go on to be a major film and television producer) were the visionaries behind the magazine, and, along with Duncan, they created its identity. But it never reached beyond its limited base in terms of sales or advertising. The magazine tried to become more mainstream in its final years, but it failed to broaden its base and eventually lost its niche, years before the lucrative LGBT market was more successfully tapped. The magazine began a slow decline in the late ’70s. Como left in 1980 to head Dance magazine. Subsequent editors realized that its tasteful eroticism couldn’t compete with the explicit male nudity in new, plastic-wrapped periodicals like Blueboy, Mandate, and Playgirl. And its star card was being eclipsed by new, well-financed celebrity magazines. By 1983, the party was over. Once it fell into decline, it’s doubtful it could have rebounded in the era of AIDS, Reagan conservatism, and the religious Right.

Many in the LGBT community didn’t mourn the loss of a magazine that gave a singular perspective on gay life: that of middle- and upper-class white gay men having a good time. Some gay activists had disdain for its closeted staff, viewing them as dilettantes and criticizing the magazine’s lack of political purpose. But it was subversive in its own way, connecting to the LGBT community on a national level with a shared cultural æsthetic. In highly closeted times, not everyone across the country—especially those far from urban centers—was on the front lines of the gay rights movement. But merely being joyously visible served an important purpose, too, making you feel you were part of something larger than your private self.

Today one can find a few issues here and there in vintage shops or on eBay. I eventually sold my collection to Demna, then the creative director at Balenciaga in Paris. I saved a few duplicate copies and occasionally flip through the glossy pages, smiling at the advertisements for caftans, hair removal, and Les Hommes book shop, at the stunning portraits full of pride and joy, and at the faces of gay young artists not yet taken by time or AIDS, recalling a decade of liberation, happiness, and hope.

Frank Rizzo is a theater writer and critic for Variety and a freelance journalist based in New York City and New Haven.