THE DISCOURSE on homosexuality is a major part of current American culture, and it doesn’t show any signs of slowing. Thus, it is all the more noteworthy that a recent production of As You Like It that ran at the Brooklyn Academy of Music earlier this year, directed by Sam Mendes and cast with a bi-national troupe of American and British actors, seems to go out of its way to suppress the homosexual dynamics that are inherent in Shakespeare’s play. An eerie sense of homophobia comes across as this production unfolds.

As You Like It offers two key opportunities for exploring contemporary notions of gender and desire: first, through the relationship between the characters Rosalind and Celia, which is set up as a same-sex pairing of intense and unorthodox intimacy; and second, through the theatrical device of cross-dressing that’s enacted by Rosalind, the heroine and mastermind of the play’s action.

Throughout the play, Shakespeare drops telling clues about Rosalind and Celia’s feelings for each other.

In her Sexual Personæ (1990), Camille Paglia recognized a homoerotic potential between the two female principles, mainly emanating from Celia (citing her jealousy of Orlando) and directed toward Rosalind. James C. Bulman has focused on Declan Donellan’s landmark all-male production of As You Like It in 1991, observing that the Rosalind-Celia bond resonated as especially homoerotic if only because the two characters were played by actors of the same sex, who lay in bed together and caressed each other intimately.

Harold Bloom, probably one of the most dismissive critics, writes in his 1998 treatise on Shakespeare aptly titled Inventing the Human, “Rosalind has been appropriated by our current specialists in gender politics, who sometimes even give us a lesbian Rosalind, more occupied with Celia (or with Phebe) than with poor Orlando. As the millennium goes by, and recedes into the past, we may return to the actual Shakespearean role.” Characterizing such exploration of sexual identity as “appropriation” of “the actual” role is simply shameless in its high homophobic air. Later, he asks incredulously, “Are Rosalind and Celia to marry each other?” Mendes takes up with Bloom’s outmoded approach by having the women occupy separate twin beds and by minimizing the physical intimacy that passes between them.

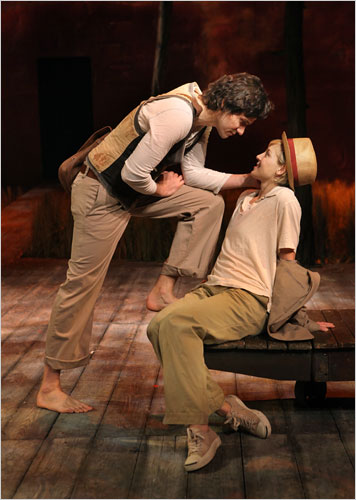

Then there’s the case of the gender-switch that occurs in As You Like It, in which Rosalind dresses as a young man to avoid being harassed while banished to the Forest of Arden. Rosalind takes for her male name Ganymede, a name that’s already homoerotically charged, as it refers to the young shepherd boy that Zeus kidnapped for his beauty and kept by his side. The complications of Rosalind’s voyage into drag and passing (and subsequent deconstruction of gender play) climax when Rosalind-as-Ganymede challenges Orlando to a game of wooing, leading up to a fake wedding ceremony—and in some performances, including that of Mendes, a kiss between Rosalind-as-Ganymede (who is pretending to be “Rosalind”) and Orlando—that draws Orlando and Rosalind into an erotically puzzling intimacy.

Keep in mind that in Shakespeare’s time the actor playing Rosalind would have been a boy—playing a girl trying to pass as a boy pretending (at one point) to be a girl. We do not have the privilege of watching this play as Elizabethans would have, with adolescent boys cast in the female roles, so we cannot know precisely how the gender pileup would have come across, or what social significance it may have had. But this hasn’t kept scholars from speculating. Bulman cites the work of Stephen Orgel, who argues that “homosexuality was the dominant form of eroticism for Elizabethans,” taking the position that the experience of Shakespeare’s audience would have been directly stimulated by the corporeality of men and young boys performing opposite each other in romantic situations.

David Cressy, Paglia, and others would argue that the Elizabethan audience would have been trained by convention to see past the gender of the adolescent boy actors and play along with the ruse. Be that as it may, in modern times, all-male versions of As You Like It were a novelty, to say the least, when they reappeared in England and North America, becoming a theatrical mainstay over the past two decades. The first all-adult-male production of Shakespeare goes all the way back to Clifford Williams’ National Theater at the Old Vic production of As You Like It in 1963, at a time when the British censors were still squabbling over representations of homosexuality on the stage, and just before the UK finally decriminalized homosexuality between consenting adults.

More recently, Edward Hall’s all-adult-male Propeller Company has achieved broad success and critical acclaim. Often these productions are hailed by critics and audiences for how well the actors’ genders disappear and allow the “authentic” characters (and therefore, we must assume, the “authentic” heterosexual experience of the audience) to come through. Cheek by Jowl’s As You Like It was similarly praised. As Bulman argues, contemporary critics, even in progressive feminist/queer academic circles, have been slow to apply the homosexual implications of cross-gender casting to contemporary productions, opting instead to look back to the Elizabethan era, where our understanding of how an audience would have received this theatrical convention is conjecture at best. For an audience today, whose awareness of gay men and lesbians and their relationships has been heightened by GLBT visibility, the gender reversal has conspicuously—perhaps dangerously—homoerotic implications.

But this is also true for non-cross-gender productions of Shakespeare’s plays in which drag and passing play major roles. For instance, in As You Like It, how odd is it that Orlando, a presumably straight male, agrees to play the wooing game with Ganymede, a person he believes to be a male, albeit a “fair youth.” For today’s audience, even this bit of “gay” play-acting would be out of the question; what straight man would agree to this? As the game progresses, the stakes are raised as Orlando and Ganymede continue to get swept up in their growing intimacy. And as written by Shakespeare, you have to believe that Orlando has come under the spell of a man, and a young boy at that.

Here, Bloom rushes to the rescue with homophobic denial, musing that Orlando probably sees through Rosalind’s male disguise and thus, knowing that the body underneath Ganymede’s clothes is female, allows himself to be drawn into physical intimacy, an assertion for which he offers no support. Bloom places Shakespeare at the epicenter of the Western canon and extols his every subtlety, his every double entendre, until it comes to the possibility that Shakespeare was perfectly aware of the titillating, homoerotic, deconstructive implications of all the cross-dressing he wrote into his comedies, further complicated by the convention of boys playing his female characters.

Mendes doesn’t shy away from using a climactic moment to reveal his own homophobic identification in the Orlando-Ganymede combination. After the kiss—which he directs, but which is not implicit in the script—Mendes presents Orlando’s immediate reaction as one of homosexual panic. At first, he’s paralyzed like a deer in headlights; some awkward body language; and then the annihilating gesture of wiping off the kiss with his hand.

Mendes then doubles-down on gay panic when Rosalind’s gender reversal finds Ganymede pursued by the wench Phebe. Mendes quite unashamedly plays up the crisis of the female-female pairing (that of the characters and the actors) by having Rosalind squirm, fidget, panic, and bat back an aggressively advancing Phebe. Where Orlando’s panic is quiet and introspective, Rosalind’s is frantic and hysterical. Remember, these are specific choices Mendes has made as a director. These scenes do not have to be played this way.

I was curious to know how directors prior to the counter-cultural revolutions of late 20th century—which helped theatre and the arts to encounter these volatile subjects—approached the seemingly inescapable homosexual implications of this play: a play that was written in many ways for a more liberal performance context than most of the 20th century had allowed. Luckily for us, cinema has been inadvertently preserving directorial choices in performance for over a century. Paul Czinner’s 1936 film version starring Sir Laurence Olivier and the Weimar-era Elisabeth Bergner preserves a specific moment when Shakespeare ran up against censorship in American film. Czinner’s As You Like It was produced just at the time the censorious Motion Picture Production Code was taking effect. The Code didn’t stop with suppressing all depictions of homosexuality—but of course there was that—but was so broad and sweeping as to censor almost anything that could be perceived as sexually suggestive or illicit, including heteroerotic representations or innuendoes.

Case in point: there’s a moment early on in As You Like It in which Rosalind makes a bawdy pun to Celia by declaring that her sadness is not for her banished father but for “my child’s father.” She is, of course, referring to Orlando, with whom she is smitten, and whom she wants to father her children—in contemporary parlance, her “baby daddy.” Amazingly, the script in Czinner’s film version is rewritten so that Celia’s inquiry into Rosalind’s low spirits is general, to which Elisabeth Bergner as Rosalind replies that her sadness is for “my father’s child,” meaning herself. This sleight-of-hand slyly subverts the allusion to fornication (out of wedlock sexual intercourse, which would have been forbidden by the Code) and replaces it with the wholesome image of Rosalind’s own parentage, which presumably occurred within the bonds of marriage.

For Mendes to have made the same choice today would have drawn critical censure. To the contrary, Mendes plays up this and other sexual puns in the play. Thus, for example, there’s a moment in the play when Touchstone is making fun of Orlando’s poorly written odes to Rosalind, reciting the line: “He that sweetest rose will find, must find love’s prick, and Rosalind.” This clear reference to the male phallus, which Mendes has Touchstone over-stress with an illustrative hand gesture, is simply glossed over by the Touchstone in Czinner’s film and taken only as a literal reference to a rose, which also alludes to the name of Rosalind.

Czinner’s film also glosses over the homoerotic implications that arise via Rosalind’s passing as a young man. There’s no kiss between Orlando and Ganymede (although there is one later between Orlando and Rosalind, of course, after they are happily wed), and thus no real challenge to Orlando’s heterosexual creds. Olivier’s Orlando is gentle, intelligent, and naïve. You kind of get the sense that even if Ganymede were an actual homosexual boy trying to lure him into a big gay trap, Orlando would simply not get it. This is in stark contrast to Mendes’ Orlando, who explicitly acts out his recognition and subsequent freakout after kissing another boy.

In addition, in Czinner’s version, when Ganymede notices that Phebe is smitten with her, Bergner meets this revelation as a playful challenge. Her eyes widen; she casts a thrilled smile; she moves toward Phebe, challenging her affection. The choice to play up Rosalind’s fearless intimidation completely overshoots the possibility that Rosalind could have any homophobic misgivings about Phebe’s mistaken crush on her male disguise. For Czinner, it would simply have been beyond the pale to suggest that the accidental same-sex pairing had any homosexual implications whatsoever.

Here is a shrewd directorial choice, made to satisfy the prohibitions of a thoroughly homophobic era, that ironically renders a more compelling case for the character of Rosalind than Sam Mendes’ contemporary, fragile, gay-panicky version does. In short, where Czinner—heeding the bluntest form of homophobic prohibition—was unable even to point to the homoerotic implications of the accidental same-gender pairing, therefore making it impossible for him to comment on it, Mendes takes advantage of a contemporary freedom to illustrate the homosexual potential, and then makes the devastating choice to contain it within the panic of his characters. This is a far more sophisticated form of homophobia than that of Hollywood’s arcane “Production Code,” which makes it all the more disturbing that it’s happening today.

At this point in Mendes’ production, we (the homophobic audience) supposedly can’t wait for Ganymede to turn back into a girl so that Orlando’s heterosexuality can be vindicated, and so that Rosalind can fully express her and everyone else’s heterosexuality in a cluster-fuck four-way wedding, which she orchestrates.

The last nail in Mendes’s homophobic coffin is hammered in with the inclusion of the epilogue. In Shakespeare’s time, epilogues were rarely performed more than once, and were not considered part of the play proper, as they were often used merely to test an audience’s reaction to the material of a new play. In the epilogue to As You Like It, the actor who plays Rosalind (in Shakespeare’s day, a young boy) comes out alone onstage and petitions the “women” of the audience to love the play as much as they love “men,” and vice versa. The actor also says, “if I were a man, I would kiss as many of you as had beards that pleased me.” Shakespeare, knowing that this would be delivered by a young man dressed as a woman, was surely playing with the comic possibilities of the theatrical moment. But Mendes directs Rosalind to play this epilogue with a romantic literalness that simply wipes out any homoerotic wit or irony from the situation. Instead, we get an earnest, almost happy-to-tears petition from a female actress, telling us that all the men in the audience surely love women, and all the women surely love men. It’s as if Mendes is discounting the possibility that any members of the audience could be gay.

All of these directorial choices—to use a potentially homophobic epilogue which is non-obligatory, to contain homosexual implications and possibilities within debilitating displays of gay panic, and to suppress homoerotic motivations of characters as written by Shakespeare—are offensive to a contemporary sensitivity to homosexual representation. At the very least, they intentionally play into contemporary homophobic modes of response to homoeroticism. Mendes, in my considered opinion, should seriously rethink his homophobic approach to this undeniably queer play.

Ryan Tracy is a cultural critic and a regular contributor to New York Press (nypress.com).