AROUND THE TURN of the 20th century, “virile” (from the Latin virilis, manly) was an adjective frequently used by art critics to characterize American paintings. The boldest and most independent painters were conventionally designated as “virile,” while those who depended on European models were by implication not as masculine or even effeminate. Thus there were also nationalistic overtones to this term. “Virile” had connotations of mental health and moral purity as distinct from European decadence and corruption. Modernism itself was judged a European import that American artists would do well to avoid.

Critic Charles Francis Browne attributed to one group of American artists “a sanity, a virility, a wholesome element in much of the home art that is lacking in that done in the Old World.” In 1919, Charles Woodbury, who established a summer school for plein-air painting in Ogunquit, Maine, suggested that America was a more vigorous place than Europe: “The American people are full of life and their natural expression is force … we are not soft—not dreamers only.”

More than any painter of the 19th century, Winslow Homer (1836-1910) embodied the sturdy loner, a distinctly American preoccupation. Homer’s paintings often showed images of men braving the harsh conditions of winter, far from the comforts of urban life, and he tended to utilize broad brushwork as opposed to the linear, smooth technique associated with the European academies. His vigorous, forceful realism was a challenge to genteel, decorative, and sentimental art. Rilla Jackman, in her 1928 survey book, American Arts, captured this sentiment: “It was his work that first made critics realize that America was, indeed, developing a national art true to the character of the American people. It is virile.” Decades later, in 1990’s Reckoning with Winslow Homer, Bruce Robertson explored the legend of Homer as “the John Wayne of American painting.”

American Impressionism and The Eight

The painters who came after Homer, like the art critics, often used the word “virile” to describe their work.

Unlike the Boston impressionists, who were tied to polite society and orderly summer retreats, artists such as Homer and Redfield distanced themselves from the French impressionists’ urban themes. American imagery became more focused on rugged nature, often set in remote locales such as Monhegan Island and even more savage, uninhabited places. The true American artist was a loner, emulating archetypes like James Fennimore Cooper’s Leatherstocking and frontiersman Daniel Boone, who mistrusted civilization and its rules and constraints.

A group of artists known as The Eight made their debut at an exhibition in 1908. Despite their attraction to urban themes, these painters were known for their dynamic, vital, masculine works. The big city offered some opportunities because it had its share of anarchists, street urchins, prostitutes, and backroom boxers who were often at odds with the law. This was the “raw life” of New York City, which Robert Henri (1865-1929), George Luks (1867-1933), and George Bellows (1882-1925), among others, loved to paint. These American artists could preserve their claim to manly vigor by turning their backs on Old World conventions for presenting urban themes. An anonymous reviewer commented in 1909 on the National Academy of Design’s spring exhibition: “Its canvases have a fresher complexion, a look of great virility. It is … as though [the exhibition]were more Americanized.”

During the Teddy Roosevelt era, it appears as if American artists felt they had to overcompensate for the fact that, compared to sailors or steel workers, their work did not involve manual labor or physical toughness. Painting and poetry might be thought of as belonging more to the realm of women. For example, in the May-June 1893 issue of Methodist Review, one Charles W. Rishell linked “aesthetic cravings … to effeminacy and voluptuousness.” Upon entering politics, Roosevelt, from a well-to-do background with a Harvard education, found it expedient to revamp his image through manly pursuits such as waging guerilla warfare in Cuba or hunting big game in Africa. American artists followed T.R.’s lead in publicly exhibiting their masculine pursuits.

George Bellows, for example, jumped through hoops to get into a college fraternity and to become a member of the baseball and basketball teams. His contemporaries described him as cocky, walking with a “swashbuckling air.” Studying under Robert Henri at the New York School of Art, Bellows found a masculine camaraderie—the class even had its own baseball team—and his paintings of boxers show a raw violence expressed in an appropriately dramatic, almost sensational technique. Bellows proved that art could be brutal and masculine, as boxing took on a new role in the fight against America’s increasingly urban (read effeminate) culture. Artist George Luks adopted an even more exaggerated masculinity by circulating a tall tale that he had once been a professional boxer named “Chicago Whitey.” His pictures of highly aggressive wrestlers bolstered this idea. Luks was an obnoxious boaster, a brawler, and a drunk who believed he was the reincarnation of Frans Hals, a great master who acquired a reputation, probably undeserved, for engaging in unrestrained drinking sprees and for abusing his first wife.

Most members of The Eight, also called the “Black Gang,” worked to replace the image of the bohemian, elitist artist with the manly, vigorous, even rowdy painter who would tackle the tough subject matter, whether smoke-filled bars in Greenwich Village or perilous blizzards in the great outdoors. At this point the ideal for American art was no longer the solitary explorer or pioneer. Now masculinity could display itself as drunkenness and broken marriages (Luks and Ernest Lawson), bigamy (A. B. Davies), promiscuity (Everett Shinn), or roughneck brawling (Luks).

The American Scene Movement

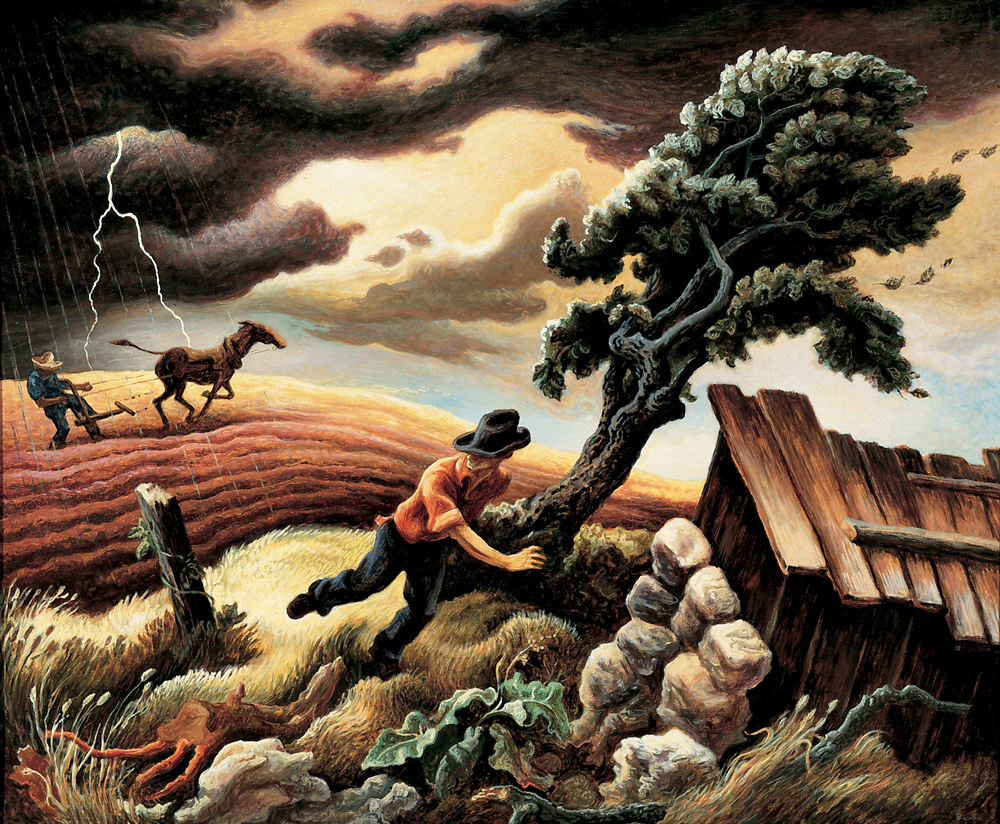

The banner of virility would be raised to new heights alongside the American flag during the American Scene painting movement. It was an era that art critic Thomas Craven would praise for its home-grown, down-to-earth style, as exemplified by the art of Craven’s friend Thomas Hart Benton (1889-1975), who stood fast against the influence of “degenerate” European Modernism. In his personal “macho” crusade Benton would join Craven in ranting against the “deviant” sexual behavior that they saw lurking in the

world of sophisticated art. Craven discerned a sharp contrast between the art of healthy, rural, hard-working Americans and the mannered European bohemians and snobs. As late as 1949, Congressman George Dondero of Michigan railed against European Modernism as a threat to traditional American art. This supporter of McCarthyism declared: “So-called modern or contemporary art in our own beloved country contains all the isms of depravity, decadence, and destruction. … All of these isms are of foreign origin, and truly should have no place in American art.” Craven, in order to place his heroes—Benton, John Stuart Curry (1897-1946), and Grant Wood (1892-1942)—on a pedestal, would demonize the European modernists as “impostors.” Cézanne and others were condemned, while Picasso was accused of producing “framed rubbish.”

Homophobia was part of Craven’s demonization process. It was already a widely entrenched attitude, as prevalent in avant-garde circles in Europe as in small-town America. Disdain for sexual minorities was embraced by almost every social group and across the political spectrum. The intolerant and authoritarian André Breton, a leading proponent of Surrealism, condemned what he called deviant sexuality. More than once he refused to allow any discussion of homosexuality, even within the context of a 1928 roundtable forum on sexuality that was supposed to cover every aspect of sexual relations. Breton and his fellow “good old boys” chastised bisexual Surrealist poet René Crevel (1900-35) for his departures from the straight and narrow. Poor Crevel, already on a teeter-totter psychologically, having witnessed his father’s suicide by hanging and endured mental abuse by his mother, did manage to return to the Surrealist fold but ended up gassing himself.

Back in the New World, gay modernist artists such as Marsden Hartley (1877-1943) and Charles Demuth (1883-1935) fought an uphill battle against homophobia, which was the weapon of choice against art perceived as having a “feminine” side. Things were no easier for artists who deployed a more realistic or representational style, such as Paul Cadmus (1904-99), who chose to confine his work to private circles. Anti-gay rhetoric also served the cause of nationalism in this jingoistic era. Craven declared French modernism to be “an emasculated tradition.” American parvenus, “victims of a bohemian corruption,” were seen as a clique of tea-sippers. Craven was especially disturbed by any ambiguity in sexual self-identification. He was suspicious of America’s art museums and university art departments, run by “a priesthood … infested with inverts. … It is, in the main, ignorant of American life and cares nothing for America’s cultural needs.” Moreover, he saw these administrators as Eurocentric and anti-American, “glorifying a decadent modernism.”

Missouri-born Thomas Hart Benton was Craven’s answer to this new direction in American painting. The two met in 1912 in New York, after Benton had trained in Paris and experimented with various strains of Modernism. But by the mid 1920s, Benton had abandoned these efforts after discovering the works of Charles Burchfield (1893-1967), at which point he began to paint scenes of rural America. It was around Christmas, 1934, that Benton’s Self-Portrait appeared on the cover of Time magazine, and the American Scene movement was born. In the feature article, the anonymous author derided American painters who had become “spurious Matisses and Picassos” after the French style. In contrast, the piece went on to state: “Today most top-notch U.S. artists get their inspiration from their native land.” Of Benton himself, Time magazine declared: “Thomas Benton is the most virile of the U.S. painters of the U.S. scene.”

According to Benton’s autobiographies, what turned him away from European styles was a series of unwanted advances by three older men. The most direct involved an older acquaintance, a bank officer named Mr. Hudspeth, whom Benton called Hud. Hudspeth had acted as a kind of mentor, frequently taking young Tom to dinner, to the opera and concerts, and introducing him to highbrow literature. Old enough to be Tom’s father, Hud was seriously courting him in the manner of an ancient Greek erastes pursuing an eromenos. Clearly, the subtle approach wasn’t working. Disregarding Benton’s professed sexual orientation, Hudspeth decided it was time for Tom to “pay up” for some of the wining and dining. On this occasion, he deliberately gave Tom too much whiskey, forcing him to spend the night. In Benton’s words, even before he could fall asleep, there followed an awkward scene of digital penetration that could have ended in rape. Benton got dressed and felt disgusted, but “also kind of sorry for Hud. … So ended my friendship with Hud.”

Clearly Benton was traumatized by the incident. Thereafter he would pursue the athletic life, unlike most artists, and resolved to avoid the effeminate men that he encountered in the art world. These were easy targets upon whom he would take his revenge. At a news conference in April 1941, he lashed out. Reportedly drunk, the artist told everyone what was wrong with the art world in America: “It is the third sex and the museums. Even in Missouri we’re full of ’em. The typical museum is a graveyard run by a pretty boy with delicate wrists and a swing in his gait. If it were left to me, I wouldn’t have any museums. I’d have people buy the paintings and hang them in privies.” In another account, we read: “Our museums are full of ballet dancers, retired businessmen, and boys from the Fogg Institute at Harvard, where they train museum directors and artists. They hate my pictures and talk against them.”

Benton was understandably anxious during this period, as regionalism was being seriously threatened by European Modernism, and he was reacting personally because he knew his enemies—the æsthetes—looked down on his art. In Benton’s way of thinking, American regionalism had become the expression of down-to-earth virility, while those art-for-art’s-sake types, descendants of Oscar Wilde and his French counterparts Robert de Montesquiou and André Gide, had embraced homosexuality. Like Modernism itself, deviant sexuality was regarded as a European import.

Benton and Craven joined forces to campaign against art theory and Modernism in general, throwing a bit of anti-intellectualism, nationalism, regionalism, and homophobia into the mix. Their use of the word “virile,” when applied to American art criticism, took on new meanings. It signified honesty and truth, freedom from European art traditions, rugged individualism, and flag-waving nationalism. Virile artists were seen as loners or outcasts who shunned European decadence, favoring wholesomeness over genteel refinement. The exaggerated masculinity of The Eight was expressed not only through their choice of subject matter but in their painting technique. Broad, loose brushwork was identified as masculine, as opposed to the polished, linear fastidiousness associated with the old masters and women painters. Charles Hawthorne (1872-1930), who ran the Cape Cod School of Art in Provincetown, advised his students to go out and paint like savages in a spontaneous, slap-dash manner. Painting was to be an impulsive act, one that often involved the use of the palette knife. Hawthorne cautioned students not to submit sketches that were “over-finished,” declaring: “It is the virility of color that makes truth.”

Thomas Hart Benton’s most famous student was Jackson Pollock (1912-1956), who took this principle to a new level. Pollock’s explosively spontaneous approach to making art seems to be consistent with his macho attitudes, his contempt for both women and insufficiently masculine men. In his review in the Northern California Bohemian, Richard von Busack suggests that Pollock could not accept his own bisexuality: “From Benton, Pollock inherited fears of the unmanliness of doing art that was abstract instead of social realist. Pollock’s bisexuality, with which he wrestled all his life, may have been reason for his drinking and bullying.”

From the use of a paintbrush to a palette knife to a simple stir stick, by the mid-20th century American painters had reached a high point of aggressive, expressive “action painting,” epitomized by the bold, gestural technique of Pollock. The violent technique of his drip paintings of 1947 to 1951 could arguably be seen as the ultimate expression of machismo. Abstract Expressionism overshadowed every other style, and soon New York would become the international center of Modernism. After 1945, it was possible for American “virile” painters to go with the flow of Modern art, which was itself about to be transformed (again).

Michael Preston Worley, PhD, teaches art history at ItalCultura, the Italian Cultural Institute of Chicago.