Adapted from essays that appear in the forthcoming volume, The Hot Girls of Weimar Berlin, published by Feral House of Los Angeles, CA.

IF PARIS WAS historically the city of love, 1920’s Berlin was the metropolis of “Girlkultur.” Girlkultur, a curious blend of German and American fantasies and fashions that surfaced after the First World War, was one of the psychic forces that transformed a dowdy war-shattered Berlin into the modern Sapphic citadel of free thinking, freewheeling female behavior that it became. Dietrich sang of “Naughty Lola, the wisest girl on earth” and “charming alarming blonde women.” The American actress, dancer, and model Louise Brooks, who was the sultry amoral icon of Girlkultur, broke the hearts of countesses and businessmen alike. The New Woman of Girlkultur added American boldness to the Old World model of sexual sophistication. The variations of female desires that were indulged behind closed doors in New York and Paris were boldly displayed in Berlin, whose tourism-boosting slogan was “Everyone once in Berlin!”

Among Berlin’s four million inhabitants in 1930 was a vibrant “Third Sex” community of homosexual women estimated to be between 85,00 and 400,000, depending on your preferred source. Estimates have been derived from magazine subscriptions, club memberships, travel agents booking sex tourists, and sexologists who meticulously categorized the spectrum of female intimacies flaunted on the streets. These “girl friends,” whether they were stenographers, revue dancers, scholars, or shopgirls, had money in their pockets and claimed Berlin as their sexual Shangri-La by the Spree. Wrote Ruth Roellig in 1929’s Lesbians and Female Transvestites:

Lesbian emotional needs are truly inordinate. They build a world of their own—in their houses, in their lounges, in their literature, and especially in their love practices. Lesbian desires reel over stars, aromas, sounds and luminous colors. Caresses of soft and pliant hands, nail and tooth, soft bites and pulling of hair, and finally after great tension, an utter free-fall and drowning until their own egos are dissolved into a moment of measureless bliss.

The Germans’ erotic vocabulary was richer than the American notion of reducing sapphic orientation to merely “butch/femme” or “power exchange.” The sign above the Toppkeller Club restroom proclaimed: “We are the New Spirit. We do it with Brazenness!” Adding to the cultural mix, the women’s street fashions were French-inspired, but tailored with German precision. Butches could be Daddies, Garçonnes, Sharpers, Scorpions, or Tadpoles, each easily identified by a specific haircut, eyebrow styling, and cut of suit. Femme roles were equally complex. Even the boring lesbians had their own particular nightclubs, cafés, restaurants, gaming clubs, political and literary societies, sporting events, masked balls, and beauty contests, echoing the weekly magazine Garçonne’s motto, “For Friendship, Love, and Sexual Enlightenment.”

Chemical Highs

The intricate drug culture of Berlin suited a city that advertised its devotion to sensation. Part of the tourist allure of Berlin was its vast display of evening entertainments (open till 3 AM), and after-hours establishments for further debauchery. Artificial stimulants were an essential part of the social etiquette of the all-night Bummel or the whirl of artists’ balls during Karneval. If the drugs weren’t available from one’s doctor or pharmacist to remedy such problems as marriage difficulties, inordinate pain, fatigue, or sexual confusion, they were easily acquired on the streets of Berlin.

Rumpelstilzchen, the Michael Musto of Berlin, in a weekly news column from 1919 to 1932 kept track of all the fads, fashions, and celebrity quirks that were to be found in the back alleys and bedrooms. As early as 1920 he was lamenting—as well as publicizing—Berlin’s drug trade. At Alexanderplatz, which was next to the police station, morphine was easily obtainable in amounts “not just enough for a few injections, but enough to send an entire small town to the grave.” Nine out of ten waiters in Berlin’s cafés solicited cocaine orders from their customers, as other revelers openly snorted the powder in well-lit booths. Opium balls were available for sale on the street and in hidden establishments. Glue, hashish, chloral hydrate, and marijuana rounded out the highs and lows. Indispensable party props for erotic amusement were the syringe and the hand mirror, an ideal portable surface for powdered stimulants.

Adding to Berlin’s recreational drug use was the medical community’s devotion to the new field of sexual science. The study of ancient and modern aphrodisiacs and their manufacture made Berlin the wellspring for sexual pharmaceuticals in Europe. One might go to a Swiss clinic for a certain rejuvenation procedure, but Berlin was the marketplace to test its efficacy. Herbal preparations such as “Satyrin” (gold for men, silver for women) or “Evasex” were advertised in magazines and available at your local apothecary.

The use of intoxicants to enhance female ecstasy was a subject of serious scientific inquiry. Erotic urges were calibrated in the laboratory as well as in the bedroom. The effects of morphine, cocaine, and opium on blood circulation in female genitalia, libido changes throughout the menstrual cycle, habitual masturbation, and non-orgasmic gratification were some of the data collected. Hard science supported the sociological speculations about the drugs widely used by women for work and pleasure. Women artists were especially predisposed to substance abuse, relying on drugs for inspiration and performance enhancement. The other female professions scientifically determined to be especially dependent on drug use were prostitution and espionage.

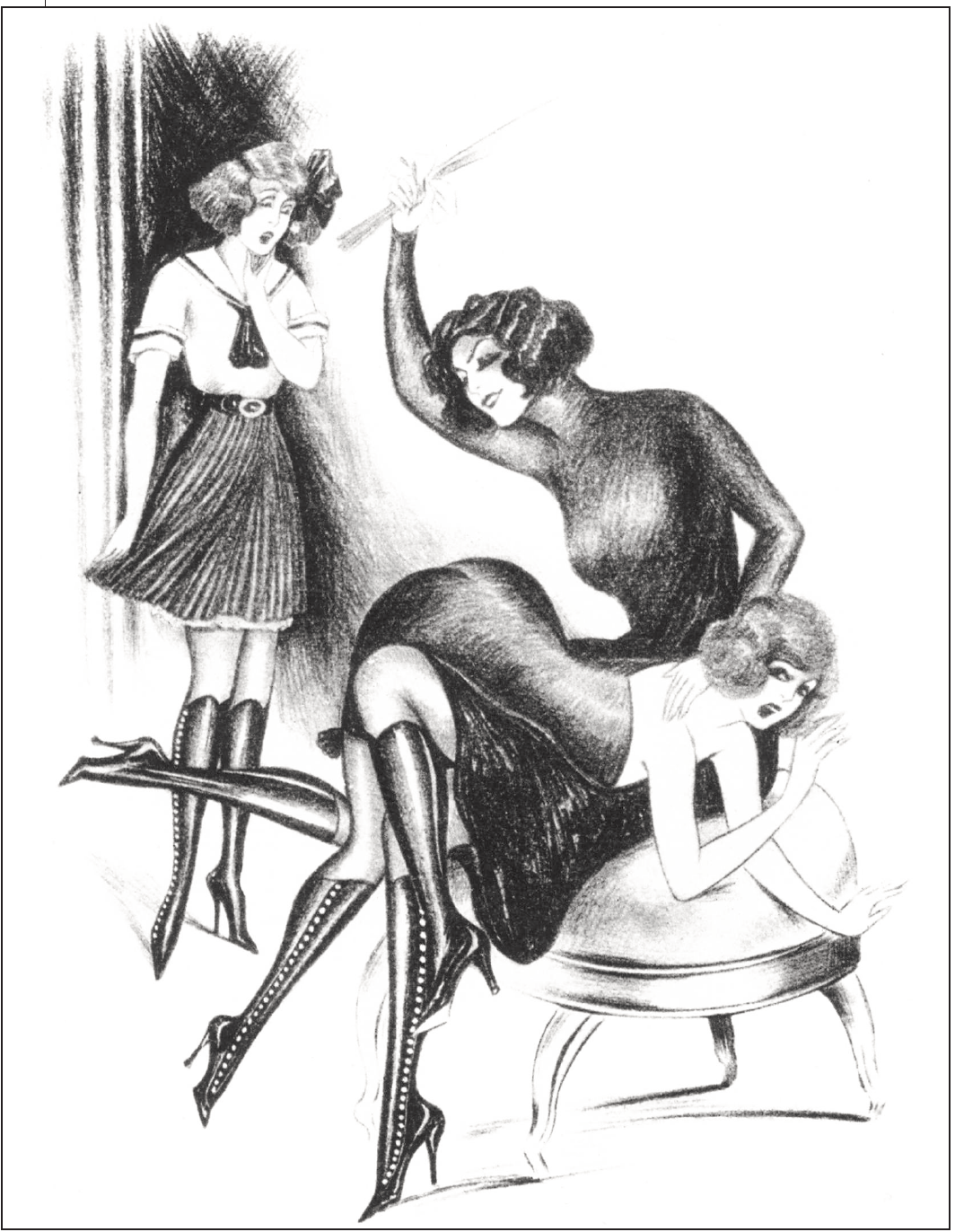

Kind Mistress

The Germans beautifully wedded kink and scholarship in Weimar publishing. No matter the twist—worshipping the Domina’s feet, flogging the schoolmaiden, or tightening the corset of the cross-dresser—there was a scholarly accounting of the perversion, complete with lush color illustrations of historical and contemporary subjects to support your research. They were expensive. And exquisitely bound. They certainly looked very respectable next to your Schiller and Goethe.

The rapidly expanding field of sexual science, a German specialty, contributed titles by medical doctors, sexologists, and psychologists. Such scholarly titles as Moral History of the Inflation or Sexual History of the World War competed with the more evocative Portrait of Intimacy, Flight from Marriage, The Elegant Woman, The Witch’s Cauldron of Love, and The Five Senses.

The wealth of ideas about female erotic authority was specifically categorized in Dr. Alfred Kind’s 1931 four-volume series (with 1400 illustrations), The Powerful Woman in the History of Mankind. The cult of the Domina could now be cross-referenced in Bilder Lexicon (1928–31), an extensive erotic encyclopedia in four volumes, each over 1,000 pages long, or Omnipotent Women: An Erotic Typology, with six volumes addressing female power.

Robert Heymann’s 1931 Moral History of Sexual Dependency, officially endorsed by Berlin’s Director of Public Hygiene, Dr. Max Marsch, addressed erotomania or “inordinate sexual passion” in The Submissive Woman and The Masochistic Man. These volumes of royal blue leather embossed with gold emblems of exotic womanhood ran the gamut with chapters on the Oedipal Complex and sacred temple prostitutes to bestiality, fetishism, and the impact of Josephine Baker and Mae West.

Available for purchase only through membership in an erotic society were flagellation novels with specific themes (Turkish harems, French gangsters, the Russian Revolution, the Court of Versailles). The “masochistic educational novels” of convents, boarding schools, and nurseries enjoyed great popularity. Whatever your specific idea of power exchange, somewhere you could find a literary anthology or private collection to cross your wires. The erotic folklore of powerful German women, vampires, or Valkyries had been entrenched in German culture for centuries, but Weimar added a modern humorous edge with its spiteful sex kittens, seductive schoolgirls, evil equestrians, and mean grandmas. Men were merely animals, puppets, and clowns in these works.

Kind Mistress recognizes the gloriously mature women of Berlin with Booted Eros: the life story of an adolescent transvestite shoe fetishist. In this 1932 memoir by Hanns von Leydenegg, beautiful women of all ages, including blood relations, force young Hanns to accept his devotion to female footwear and all the responsibilities that entails. This slim volume, bound in purple, has six exclusive illustrations of Paul Kamm’s magnificent females training sissy men for their dark needs.

Anna Elisabet Weirauch’s three-volume German novel The Scorpion (1919–21) is a perfect postwar mirror of the freedoms enjoyed by these independent women and the anxieties generated by their presence in Berlin society. The book offers an intriguing and original look at female passion in Weimar. Its impertinent opening line sets the tone: “Frankly, I desired to make Myra’s acquaintance because of her evil reputation.” The Scorpion follows the model of most 20th-century lesbian fiction, which offers few happy endings and where humor is often in short supply. Olga, the beautiful and morally suspect “Scorpion,” is an aristocratic, educated variation of the generic female butch or “bubi,” masculine women first identified by their distinctively male fashion choices and coiffures. Not only did The Scorpion feature beautiful women as sexual predators, but the novel’s primary romance was between two distinctly masculine lesbian types: Myra, an androgynous young garçonne, and Olga, a sophisticated, elegant “scorpion” or “sharper.” This relationship veered widely from the standard boarding school romances or naughty maid scenarios of traditional Prussian society, girly-fun fantasies that did not threaten the core of Prussian masculinity.

The marvelously refined Scorpions wear fabulous clothes, speak many languages, understand music and art, ruthlessly corrupt unsuspecting wives and daughters, and live exclusively without men in a degenerate world of their own creation—which is to say, in Berlin. Myra could be the great-grandmother of Diane Di Massa’s “Hothead Paisan: Homicidal Lesbian Terrorist” of contemporary comic book fame. She’s a butch with a broken heart, she doesn’t follow the rules, and her hormones are way out of control. Here, then, is Myra’s sad tale: “The motherless poor little rich girl Myra is first wounded in a tragic youthful crush on her flirtatious governess, which fills Myra with a deep mistrust of pretty women. When the young heiress meets Olga, ten years her senior, Myra falls desperately in love with the dark woman of her dreams.”

Myra’s erotic modern misadventures were light years ahead of The Well of Loneliness and Orlando. The Scorpion proved so popular that it was published in English in 1932, translated by an American writer then working as a spy in the Communist underground, Whittaker Chambers. Mr. Chambers’ family life may have been as turbulent as Myra’s, with a bisexual father, artist mother, mad grandmother and suicidal brother, allowing him to easily tap his inner sapphic. That edition combined volume one and two, ending with Myra’s betrayal by the evil nymph Gwen. The third volume The Outcast was translated by Guy Endore but not released until 1948, the same year The Scorpion became a more erudite staple of American lesbian pulps with the drab subtitle “an understanding study of twisted emotions.” Yet, despite its distinctly formal prose, Myra’s exotic world is filled with the same dyke drama (girls, money, real estate, lesbian bed death) that resonates in the heart of today’s baby boi and her paramours.

Barbara Ulrich is an independent filmmaker living in Manhattan. the Hot girls of Weimar Berlin is her first book.