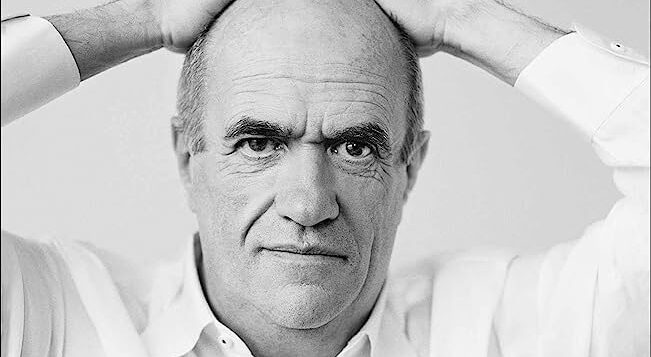

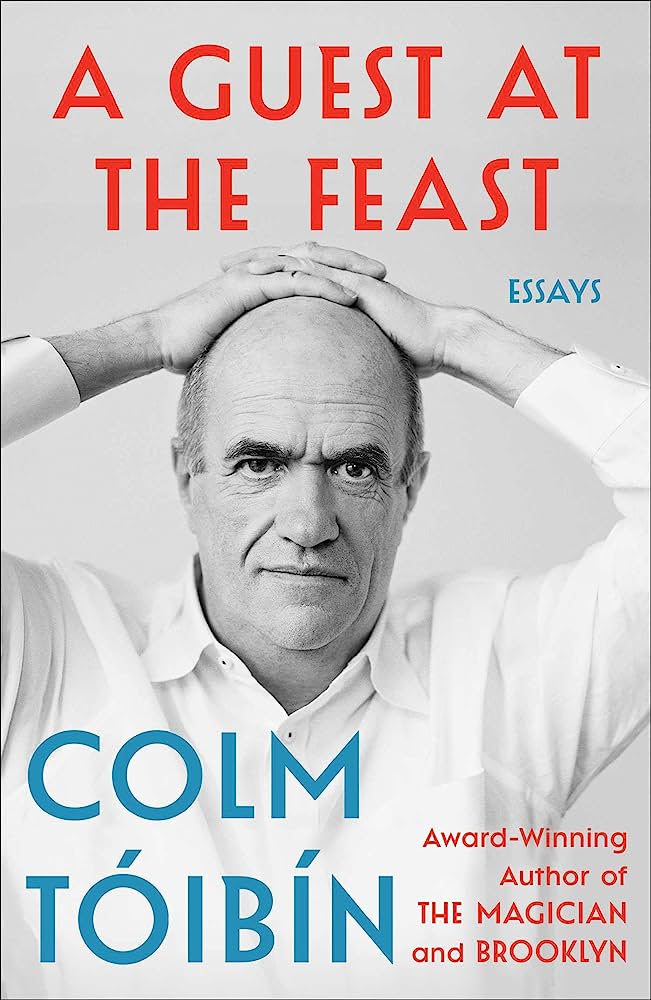

COLM TÓIBÍN has a calm, mildly humorous voice in several genres and as a literary critic and professor. He’s probably best known for his descriptions of his native Ireland in novels about women—The Blackwater Lightship, Nora Webster, and Brooklyn (which was made into a movie starring Saoirse Ronan as a young Irish immigrant to New York City in the 1950s)—as well as his novels exploring the lives of two influential 20th-century writers, Henry James and Thomas Mann.

In this collection of essays, originally published from 1995 to 2022, Tóibín discusses personal topics (his bout with cancer, the small town where he grew up) and public topics (the legal status of homosexuality in Ireland, priests and popes, the work of other writers). As an openly gay man from a notoriously homophobic culture, he seems to have found a certain comfort level as a citizen of the world with an engaging public persona. He divides his time among homes in Ireland, New York, Los Angeles, and Spain.

Tóibín’s sexuality is treated almost as a peripheral issue, a personal characteristic that was not spoken of for many years. In an essay on a constitutional challenge to Ireland’s laws against homosexuality in 1980, which Tóibín covered as a journalist, he describes the double consciousness of his community: “In George Orwell’s 1984, the most severe punishment for citizens was to forbid them the right to love. To most readers of the book, this seemed a cruelty far-fetched and almost impossible, but for most gay people it was a nightmare we inhabited while pretending, sometimes even to ourselves, that it was nothing, or while telling ourselves that it would not easily change and that it was dangerous to complain.” The challenge to Ireland’s laws in 1980 was an opening shot that seems to have raised the issue for general discussion, but those who hoped for homophobic laws to be struck down had a long wait ahead of them. Homosexuality was not decriminalized in Ireland until 1993.

Tóibín’s sexuality is treated almost as a peripheral issue, a personal characteristic that was not spoken of for many years. In an essay on a constitutional challenge to Ireland’s laws against homosexuality in 1980, which Tóibín covered as a journalist, he describes the double consciousness of his community: “In George Orwell’s 1984, the most severe punishment for citizens was to forbid them the right to love. To most readers of the book, this seemed a cruelty far-fetched and almost impossible, but for most gay people it was a nightmare we inhabited while pretending, sometimes even to ourselves, that it was nothing, or while telling ourselves that it would not easily change and that it was dangerous to complain.” The challenge to Ireland’s laws in 1980 was an opening shot that seems to have raised the issue for general discussion, but those who hoped for homophobic laws to be struck down had a long wait ahead of them. Homosexuality was not decriminalized in Ireland until 1993.

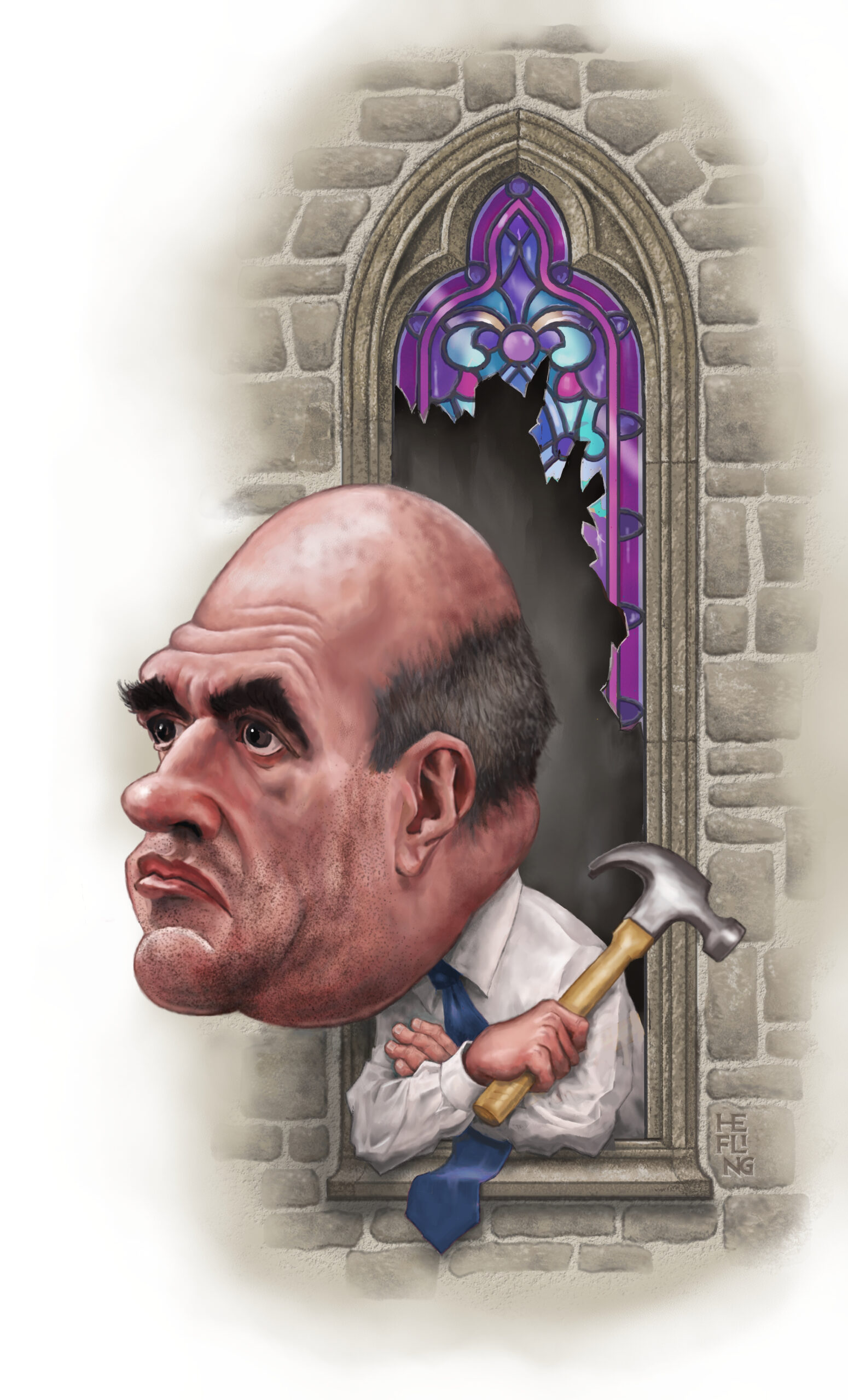

Another, somewhat related issue that Tóibín tackles is the public reckoning with sexual abuse within the Catholic church. In the 2010 essay, “Among the Flutterers,” Tóibín says that “the power of the church in Ireland has been fatally undermined” by several reports which exposed the widespread sexual abuse of children and youth by members of the clergy, and the general failure of church authorities to deal with it. In an essay from 2005, the author describes the privileges that a student could gain by “becoming friends” with a teaching priest in St. Peter’s College, the church-run boys’ school he attended. The exact nature of these relationships was open to speculation.

In the 1990s, three of these priests were charged with various sexual offences against students, and the school system that enabled this behavior was analyzed in a government report. Tóibín does not claim to be one of the victims. However, he explains why an attraction to boys might have seemed like a religious “calling” to most of the men, who chose a supposedly celibate life as an alternative to a “normal” life of marriage and child-raising, and why none of the offenders seemed like monsters at the time he knew them.

Tóibín no longer identifies as a Catholic, but the Church and its teachings still clearly fascinate him, and he claims to believe in a spiritual reality beyond the limits of the physical world. His adult ambivalence about the church enables him to write about oppression and abuse in Catholic institutions in the even-handed, journalistic style that he developed in his twenties while writing for the Irish media and editing Magill magazine.

The power of religious art lured him to Italy during the pandemic. In his last essay, “Alone in Venice,” Tóibín recounts his intimate encounters with various churches, statues, and paintings at a time when the usual crowd of tourists had been replaced by a resounding silence. By this time, Tóibín had recovered enough from his bout with testicular cancer to recount this medical journey in a detailed essay ending with the words: “The age of one ball has been set in motion.” Self-pity is clearly not part of Tóibín’s style, and readers can only hope that he will continue to observe the world in good health for many years to come.

Jean Roberta is a widely published author based in Regina, Sas-katchewan, Canada.