THE AMERICAN classical music composer Samuel Barber (1910-1981) grew up in wealthy suburban Philadelphia, part of a music-loving family that included his aunt, Metropolitan Opera star contralto Louise Homer, and her husband Sydney, a minor composer. As a result, young Sam was able to meet and move in the world of the major figures in the East Coast classical music scene at an age when most music students would have just been looking on in awe from afar. A new book by Howard Pollack, Samuel Barber: His Life and Legacy, covers the life and music of one of American classical music’s best-known composers.

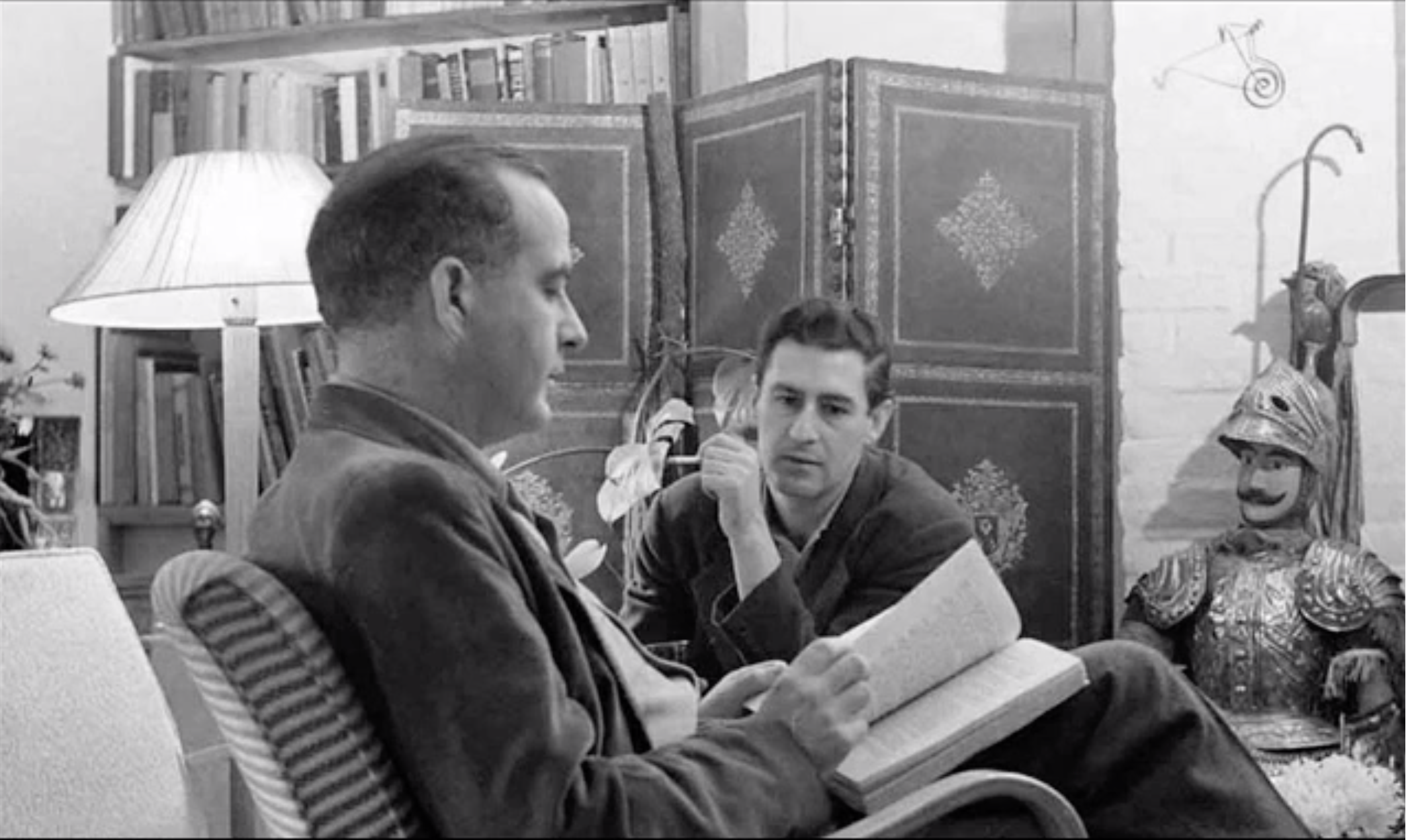

Barber gained admission to the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia, then as now one of the nation’s great music schools. There he studied composition, but also voice and piano, with thoughts of pursuing all three professionally. At Curtis, he also met and fell in love with the Italian-American music student Gian Carlo Menotti, who would himself go on to compose some of the most successful American operas of the 20th century, including the Christmas classic Amahl and the Night Visitors (1951). Barber and Menotti lived together and remained lovers for years, functioning as a couple in a world that evidently didn’t contemplate that they might be anything more than friends.

Barber was able to travel to Europe in the late 1920s and ’30s. There he met conductor Arturo Toscanini and other luminaries, and got to hear some of the avant-garde music of the time. While he was always aware of this kind of music and later incorporated more of it into his compositions, he never strove to be at the cutting edge of Modernism.

He first drew significant public attention in 1931 when Alexander Smallens conducted the premiere of his School for Scandal Overture as part of a concert with the Philadelphia Orchestra, one of the nation’s most prestigious symphonic ensembles. It was followed by several other important premieres, again with major orchestras led by distinguished musicians, including the Adagio for Strings (1938), which Toscanini premiered with the NBC Symphony Orchestra on one of his nationally broadcast weekly concerts. As a result, after George Gershwin died in 1937, Barber became one of the nation’s most respected and performed living classical composers. He continued to occupy that position for the next two decades.

When the Metropolitan Opera decided to commission a new opera from an American composer, no one was surprised when they turned to Barber. He asked Menotti for a libretto, and the two created Vanessa (1957), which had a respectable initial run and has subsequently, like the best of Barber’s concert music, been performed regularly here and in Europe.

Finding himself increasingly dismissed by the American avant-garde, Barber started to incorporate more dissonance and unusual harmonies into his music. The result was that his newer compositions often met with polite but tepid receptions. This trend came to a head with Antony and Cleopatra (1966), an opera that the Metropolitan Opera commissioned for the opening night in their new house in Lincoln Center. While the chaos of the first performance has evidently been exaggerated with retelling, it did not go well. The massive sets—dreamed up by director Franco Zeffirelli with the approval of general manager Rudolf Bing, because they felt the opera wouldn’t succeed on its own—caused problems. The large cast was insufficiently rehearsed because Barber didn’t finish the score until two weeks before opening night.

Part of the blame for the work’s poor reception rested with Barber’s score. Far less tuneful than Vanessa, it strikes me as an endless string of fragments suggesting no clear direction. The notes don’t sound as random as in some of the avant-garde pieces of that period, but neither do they involve us, or let the characters convey recognizable emotions that might draw us into the story. It would take composers like John Adams and Philip Glass to show how avant-garde opera could be both musically innovative and emotionally appealing.

Antony and Cleopatra’s failure sent Barber into a depression. His relationship with Menotti, which by then had become an open one, fell apart altogether. In 1973, they sold Capricorn, the home outside Philadelphia where they had lived for so many years. Barber kept composing, on average one major new piece a year, but none of them entered the standard concert repertory. I don’t have the data, but I suspect Barber’s concert music, with the exception of a few major works like the Adagio for String, the Violin Concerto, and Knoxville Summer of 1915, no longer figures regularly on the programs of the world’s major orchestras. Among his American contemporaries, Aaron Copland is certainly encountered more often in performance today.

Who, then, might be interested in a 700-page life-and-works study of Barber? Pollack’s biography interweaves twenty chapters on the composer’s major works with nine chapters on his life. The latter do a good job of situating Barber in the American classical music world of his era. Because he knew virtually everyone from an early age, the biographical chapters offer windows on the activities not only of Barber and Menotti, but also of Copland, Leonard Bernstein, and many others.

Some things are lacking that could have been interesting. We learn very little about what music Barber encountered while in Europe in the 1930s. Perhaps there is no documentation on this, but brief sketches of who was performing what while he was in Vienna or London might have been useful. It would have been interesting to learn what Barber thought of his contemporaries’ works, but he evidently left nothing about that either. In fact, he doesn’t seem to have shown much interest in any of them. Nor does he appear to have thought of himself as a particularly American composer, unlike, for example, Copland or Gershwin. And he did not see himself as a gay composer.

Perhaps not surprisingly, today’s leading American classical composers don’t seem to demonstrate any desire to emulate Barber. Howard Pollack greatly admires Barber but admits that he had a “relative unconcern with creating a distinctive style of his own or anything particularly original.” It’s hard to continue in the line of someone who never really created a distinctive line of his own.

Richard M. Berrong, a professor of French literature at Kent State, makes documentary films about World War II in France.