THE FIRST GLIMPSE I had of Thom Gunn was his picture in a poetry anthology titled The Modern Poets, edited by John Malcolm Brinnin and William Read. It was assigned as a textbook in an English literature class I was taking at Emory University in 1963, with consequences for me that the teacher could not have anticipated. That anthology was the first to include pictures of the poets alongside their selection, a bonus that always makes the reader curious about how the writer’s appearance bears on the work itself. Most of the poets (all but one of them white) looked like solid, middle-class citizens, the men often in jacket and tie, the women in suit dresses. That included Elizabeth Bishop, a serene presence with hair in a neat short cut. (A decade later she would dedicate her poem “The End of March” to Brinnin and Read. By then I would know that the editors were in fact a couple.)

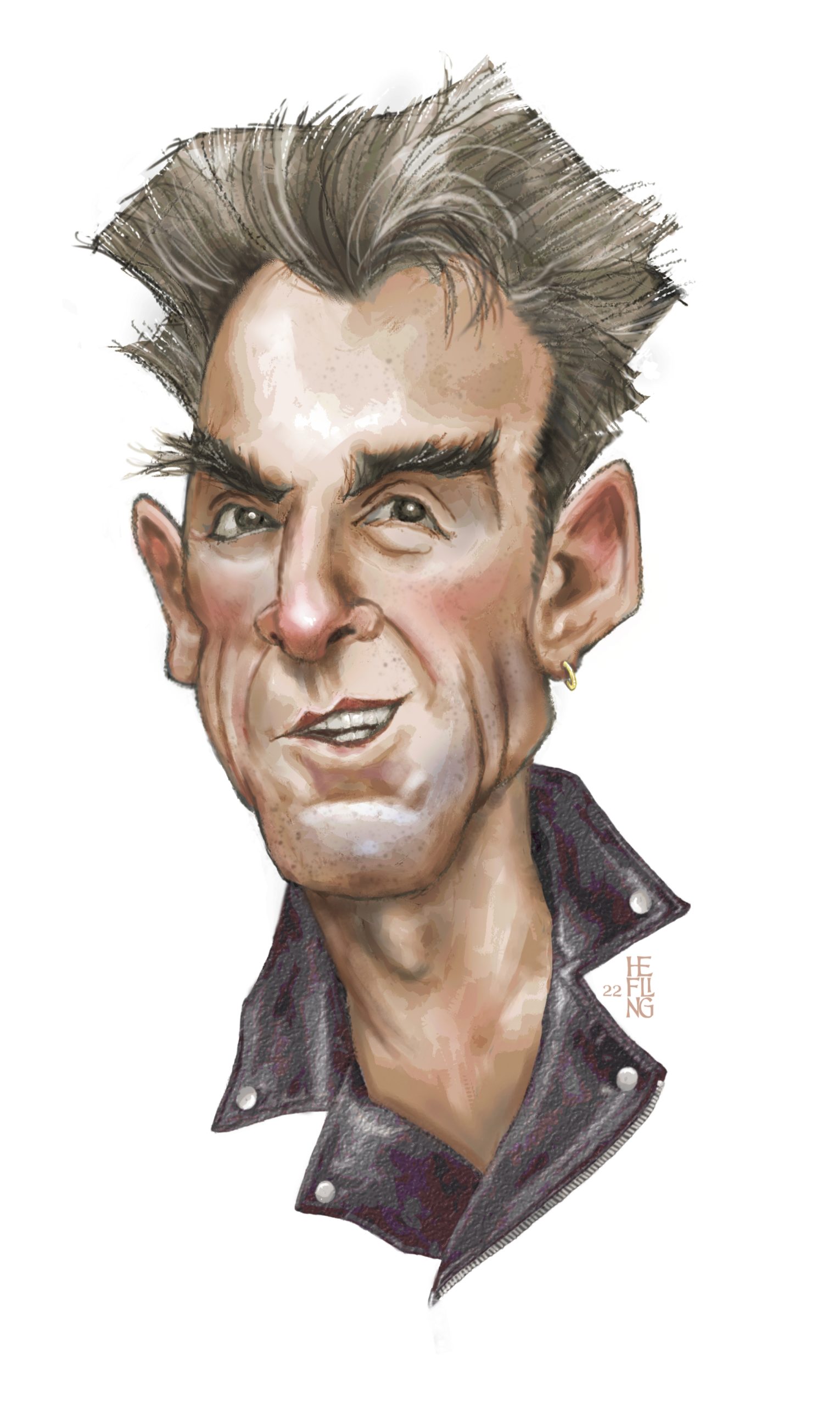

The anthology was my first exposure to Bishop and also to James Merrill, photographed in a shirt with the top button unbuttoned and seated in front of his piano. Eventually, I got to the photo of a lean, tough-looking customer with deeply creased cheeks, wearing tight jeans and a leather jacket, outdoors in open air and sunlight, a cigarette jabbed in his mouth. He was identified as Thom Gunn, a name as striking as his appearance, which fit (as did his tight jeans) the longish poem next to it. That was titled “On the Move,” and its subject was unorthodox: bikers, resembling those in the Marlon Brando film The Wild One. After a description of their leather, their goggles, and their bikes, Gunn says:

Exact conclusion of their hardiness

Has no shape yet, but from known whereabouts

They ride, direction where the tires press.

They scare a flight of birds across the field:

Much that is natural, to the will must yield.

Men manufacture both machine and soul,

And use what they imperfectly control

To dare a future from the taken routes.

Thom was determined to “dare a future” from roads not usually taken by poets, in an act of will needed for “soul making.” He had determined that a soul would be most authentically made if he lived as an outlier, an unapologetic queer renegade, indifferent to middle-class values and literary coteries. In the recently published collection of his letters (The Letters of Thom Gunn, selected and edited by Michael Nott, August Kleinzahler, and Clive Wilmer), he mentions Brando admiringly several times, an admiration that began with The Wild One. It prompted Thom to get a “hog” himself and ride around in it for a while, until his authentic self-understanding prompted him to let it go. His time was better spent at the writing desk.

§

In the following years, I read his books and got to know more about him. My guess about his sexuality was confirmed. English by birth, he’d immigrated to the States mainly to be with his American partner, a theater director named Mike Kitay, who’d come to England to study, like Thom, at Cambridge. It was the beginning of a lifelong relationship. But the official reason for his expatriation was that he’d received a fellowship (what the British call a “studentship”) at Stanford to take courses with Yvor Winters. Winters was a professor-poet rather on the margins of the American poetry scene, partly because he was anti-Romantic, urging the importance of reason in poetry, and partly because his poems used traditional meter and rhyme, just as Thom’s did. And then there was San Francisco’s unofficial poet laureate, Robert Duncan. I don’t think Thom knew about him until some years later, but Duncan became important to him, not so much because the San Franciscan’s poetics could be appropriated, but because he was the one of the first U.S. writers to live and write openly as a gay man. San Francisco’s very large openly gay community can only have seemed a promised land to Thom, native of a country where most queer folk stayed resolutely in the closet.

In the mid-1970s, I began publishing my books and, at some point, sent something like a fan letter to Thom. He answered it, but on a postcard, like all the others he later sent. (While none of these are included in the letters volume mentioned above, they are deposited at Yale’s Beinecke Rare Book Library.) In his poem “Interruption,” he says: “I manage my mere voice on postcards best.” Only close friends ever got a full-dress letter, I gather, but his postcards always managed to say something substantial. I continued to write to him. Meanwhile in my third book I began using traditional meter and rhyme, prompted partly by Thom’s example. I hoped he would, at least on that basis, like it, but, in one of his postcards, he said he found it “disappointing.” I shouldn’t feel too bad, because elsewhere poets as grand as Wordsworth, Auden, Ashbery and Merrill are resoundingly dismissed. Truly original writers tend to give low marks to others because developing a style and a distinctive subject matter forces you to exclude other possibilities.

From 1977 to 1982 I lived in New Haven, partnered with J. D. (“Sandy”) McClatchy, who taught at Yale. When he wasn’t given tenure, we moved to New York, temporarily renting James Merrill’s New York apartment on East 72nd Street, at which James (or “Jimmy,” as we called him) only occasionally stayed. The following September, during an exchange of messages, Thom mentioned that he was coming to New York. I invited him to drop by; he accepted. I introduced Sandy to this tallish, lean man dressed much as his Modern Poets photo had pictured him. He was aloof and ironic in manner, maybe slightly condescending. He said he had met Jimmy some years before, in Berlin, as far back as 1961. He was somewhat interested to hear that we were staying in his apartment. We, as well as Jimmy, had read his favorable review of Mirabell: Books of Number, which had appeared a few years earlier in The San Francisco Review of Books. Like Jimmy, he admired Elizabeth Bishop’s poetry; but otherwise there was little overlap in their taste and “lifestyle.” (In his letters he says he doesn’t like any poet who writes elegantly about opera, as both Sandy and Jimmy did, with considerable flair.) The mere fact of being gay isn’t, in itself, sufficient to create a close friendship or inspire admiration for another gay person’s writing.

I’d hoped that Thom and I might get to be on close terms, but we never quite did, partly because he didn’t often leave San Francisco, just as I didn’t often get to San Francisco. Also, I think he regarded the poetry circle I belonged to as a bit on the conventional side. None of my friends was into leather bars or the biker scene. On the other hand, Sandy and I were a decade and a half younger than Thom, and back then people often said we were good-looking. Physical appeal (to understate) was something to which Thom was not indifferent. During that first visit, he asked where the john was and went off to take a piss. Sitting in the living room, we heard him whistling some tune or other. Loudly.

The exchange of letters (or postcards) continued, though, and eventually, when Thom was awarded a poetry prize from Brandeis University, I was asked to substitute for him at the award ceremony because he didn’t want to make the trip just to pick up a medal. I did, and sent a letter afterward, with a bit of doggerel in it: “Isn’t it fun/ Being a pun/ For Thomson Gunn!” But I’m not so sure he was amused at being part of that equation. There was only one Thom Gunn, full stop.

§

In the fall of 1984, during a reading jaunt to the West Coast, I had a chance to see Thom on home ground. I was staying for a few days with friends in San Francisco (the Mission District, to be exact) before giving a reading at Berkeley. Thom asked me to lunch, telling me to come to his house in the Haight, so I took a bus from the Mission District past brightly painted gingerbread Gothic houses and spherically trimmed camphor trees to Cole Street. The rest of the way I walked, past Parnassus, Waller, and Alma Streets to No. 1216, where I knocked—late to the appointment because of traffic snarls. Thom bounded downstairs and said we should go directly to the restaurant where he’d booked a table. A five-minute walk to a simple place crowded with ferns, where we had a tasty meal. Thom looked a little heavier than when I last saw him, deeply suntanned, with a small gold ring in his earlobe, which was not so common an ornament at that time. The tattoo on his arm had been there since the early 1960s, long before any non-working-class person dared to have one. His voice was resonant, breathier and higher in pitch than you might expect, with an accent that was sort of American-flavored British. I remember I was wearing a white polo shirt that clung to my very worked-out chest and noticed Thom’s eyes straying down to it several times. Thom had a certain English reserve, so I had to scrounge for conversational topics, asking him, for example, what he’d been reading. The answer was unexpected: Francis Parkman’s classic history of Canada—also a favorite of my friend David Plante, though I don’t think they ever met.

As for his writing, he told me a curious thing: he never gave a new book to his publisher until he had already written the book that would follow it. The reason was that he didn’t want the reception of one book to influence the composition of the next. In fact, too negative a response might discourage him from writing at all. Most writers (fibbing, I suspect) say they don’t read reviews or, if they do, aren’t influenced by them. Books composed in advance were Thom’s solution to this dilemma.

We walked back to 1216 and entered an odd living space consisting of connecting rooms on two levels. Mike Kitay was away somewhere, but his collection of enameled metal advertising signs covered the walls: bright pictures of soda pop bottles in rainbow colors, with brand names from earlier decades (phallic symbols if you wanted to see them that way). In an adjoining room, there were other collectibles: brand-name beer coasters arranged on a wall in a lozenge pattern and a glass case with little pop culture figures like the comic strip characters Dagwood, Paul Bunyan, and Superman. There was a little more casual conversation before it occurred to me I should be on my way before anything awkward happened. I left, turning our time together over in my mind. Thom’s life habits were anything but routine, certainly different from mine and my friends’, but they were sincerely bound to his identity and need no apology.

The next day I read in Berkeley, with Thom in attendance, but there were so many people crowding around after (including Robert Pinsky, Leonard Michaels, and Brenda Hillman) that Thom couldn’t say much, except to offer compliments before leaving. From there I was scheduled to fly to the next reading at UCLA, so I didn’t see Thom again.

However, he came to New York about two weeks later to read at the 92nd Street YMHA with James Fenton. Needless to say, I attended, but such occasions don’t allow for in-depth conversation, and, besides, I may have been a little distracted by meeting Fenton and his close friend Christopher Hitchens. After that, I only recall one encounter during the rest of the 1980s, a brief chat in the café one level above Grand Central Station’s main concourse. I admit to feeling rather dismissed, but the sugar-coating on the pill was Thom’s telling me he very much liked a poem in my most recent book The West Door. “Home Thoughts in Winter, 1778” tells the story of an ancestor of mine, a soldier in the American Revolution who spent the winter with Washington at Valley Forge. No one besides Thom has ever complimented me on that poem; yet it is the only one Thom ever singled out for praise. Perhaps it’s because the poem is about a soldier and mentions his musket, who knows? Writers have unexpected takes on each other.

§

In 1993, I reviewed Thom’s The Man with Night Sweats for Poetry magazine. For many of his readers, it’s his best book, no doubt because of the pathos of his subject, the AIDS epidemic that had ravaged both San Francisco and New York over the previous decade. I reread it this month and find its excellence undiminished. No collection of poems on this subject is better. The detail, the honesty, the unflinching gaze developed in it set it apart from other well-meaning treatments. Thom himself, by some miracle, never contracted the virus. But the death toll among his friends and acquaintances was catastrophic, and I believe living through that era changed him profoundly.

A year later, I wrote about Tom’s entire œuvre in an essay commissioned by Encyclopædia Britannica’s annual series, The Great Ideas Today. Thom was one of the five contemporary poets I settled on to represent contemporary English-language poetry—the others being Anthony Hecht, Derek Walcott, Adrienne Rich, and Seamus Heaney. He probably saw the Poetry review and definitely read the Britannica essay, because I sent it to him. He never mentioned them, though, maybe because he thought commenting on any critical assessment of his work was improper. Or he may have felt that it was presumptuous of someone so young in the art to rate his achievement, even if praising it.

I received a few more postcards from him and faithfully read whatever he published, even the blurbs he gave younger poets, some of which provoked a puzzled “What?” from me. Thom was a soft touch where his friends or even acquaintances were concerned. He also gave me a comment for my book Autobiographies, one no doubt just as puzzling to my fellow blurbees as theirs were to me. Its brevity only increased the impact: “Alfred Corn remains one of the living poets who mean the most to me.” I was stunned.

Our next meeting had not been arranged in advance. In the early 1990s, I gave a reading at Harvard’s Warren House, and when I looked out at those attending, there was Thom, who happened to be in Cambridge. We spoke afterward, but only briefly. I could tell that other audience members were impressed that he’d shown up, and, truth to tell, so was I.

We had lunch during one of his visits to New York in the mid-1990s. I remember it was at a midtown Indian restaurant, though not much of what was said. That’s the last time I saw him. He didn’t alert me to later visits, but word got out, and I wrote to ask him why he hadn’t called. No explanation was forthcoming. He stopped answering my letters. I still wonder why, but there’s little chance of finding out. I continued reading him, a little saddened that the friendship had dried up, but such events are common among artists. Finally, it doesn’t matter. I hold close the part of him that was inspiriting, which includes his exemplary courage to live according to his convictions. Above all, there is his body of work—honest, well-made and often redemptively outrageous.

In 2009 Joshua Weinberg brought out At the Barriers: On the Poetry of Thom Gunn, a collection of essays, one of them by me in which I discussed the influence that French culture and Existentialist philosophy had on him. A few months later, I participated in a celebratory event for the book organized by the Poetry Society of America. Looking out to the audience, obviously I didn’t see him, but felt, irrationally, that he was somehow there. Somehow there and still “daring a future from the taken routes,” doing so not just for Brando and the “wild ones,” but for all of us.

Alfred Corn’s selected poems, titled The Returns, appeared last April. In 2021, he published a new version of Rilke’sDuino Elegies.