MANY MODERN WRITERS had agonizing relations with their disturbed children. Joseph Conrad’s son was imprisoned for embezzlement; James Joyce’s daughter became insane; Robert Frost’s son killed himself; Ernest Hemingway severed relations with his mentally ill son, who became a tormented transsexual. Thomas Mann fathered six children in symmetrical pairs—girl-boy, boy-girl, girl-boy—between 1905 and 1919. His three oldest children—Erika, Klaus and Golo—were homosexual; Klaus and Michael, the youngest, committed suicide. Klaus enjoyed the advantages of his father’s culture, wealth, fame, prestige, and influence, but found it difficult to free himself from his father and establish an independent identity.

Thomas Mann had had homosexual affairs before marrying Katia Pringsheim, and afterwards still had powerful, though repressed, yearnings for young men. His subtle homosexual themes appeared in Tonio Kröger and Death in Venice. In Mario and the Magician, the conjuror Cipolla hypnotizes the handsome young Mario, who is humiliated and forced to kiss him in public. Thomas recorded his homosexual experiences in his Diary, which he left behind in Munich when he later went into exile and was afraid that the Nazis would seize and use them to destroy his reputation. (The English translation of 1982 censored or suppressed many sensational passages.) Thomas chose to suppress his homosexuality by marrying and enjoying a secure life. Though he would encourage Klaus’ homosexuality, he expected the son to follow his respectable path.

ka918, when Klaus was eleven years old and struggling with the changes of puberty, Thomas seemed to possess an in-house Tadzio who matched Aschenbach’s idealized adolescent in Death in Venice. In his Diary he recorded, “I am really pleased to have such a beautiful boy as a son. … His naked bronzed body left me unsettled.” Two years later, from May to July 1920, Thomas revealed his forbidden feelings for Klaus. The normally undemonstrative Thomas described using physical gestures and soothing words about platonic man-to-man love to justify and make his son accept his own rash behavior: “I made Klaus aware of my inclination with my caresses and by persuading him to be of good cheer.” Continuing to stroke his son and attributing his own perverse feelings to the boy, he commented on Klaus’ youthful writing, their common endeavor, “while sitting on his bed and caressing him which, I believe, he enjoyed.”

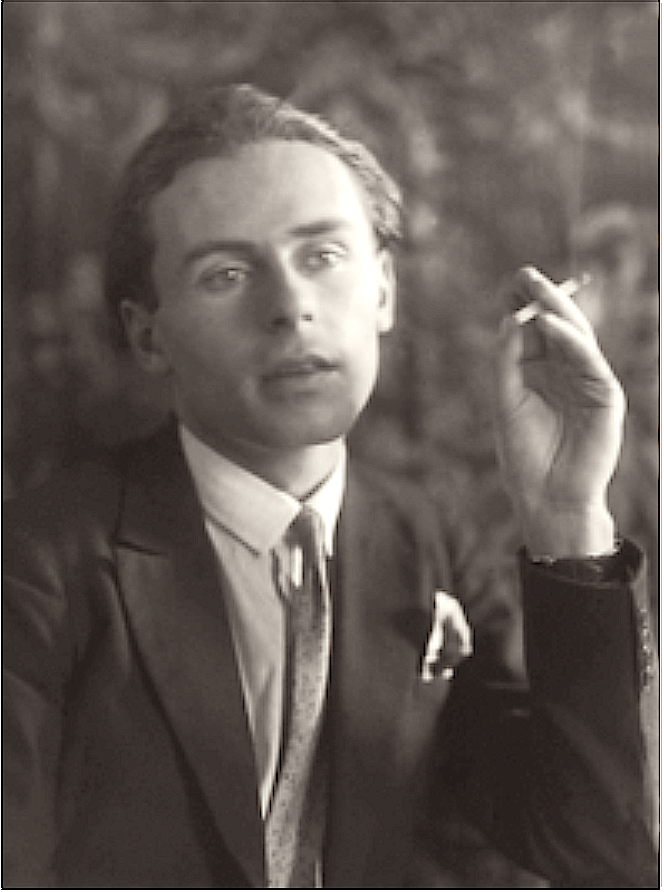

Using Klaus’s nickname—based on baby Erika’s mispronunciation of “Klausi”—Thomas blissfully wrote: “Eissi at the moment enchants me.” Intruding on Klaus when he was undressed and washing himself, he noted in an astonishing entry: “Am enraptured with Eissi: frighteningly handsome in the bath. Find it very natural that I should be in love with my son.” Excited but frightened by these feelings, he insisted that they were natural. He was also pleased to discover, while prowling around the house, what he euphemistically called “nonsense” (Unsinn): his two sons engaged in mutual masturbation: “I heard some noise in the boys’ room and came upon Eissi totally nude and up to some nonsense in Golo’s bed. Deeply struck by his radiant adolescent body, overwhelming.” Thomas was not unduly disturbed to find that his erotic obsession with Klaus made him impotent with his tolerant wife: “Doubtless this stimulation failure can be accounted for by the presence of desires that are directed the other way. How would it be if a young man were ‘at my disposal?’” The implication is that if he had a homosexual “other life,” he could get an erection with a young man. In his biography of Thomas, Anthony Heilbut stated that Klaus later “spent many stoned hours speculating on his father’s ‘abnormality,’ as if that might supply a common bond.” But neither Klaus nor Heilbut provided a convincing explanation of Thomas’ weird behavior. In the end, Thomas did not go as far as Lawrence Durrell and the religious sculptor Eric Gill, who slept with their daughters, or Djuna Barnes, who had sex with her grandmother. However, during Klaus’ adolescence, father and son were secret sharers of a covert homosexual identity. Thomas initiated Klaus into homosexual practices that he himself had physically, but not emotionally, repressed. As a child, aware of his father’s sexual obsession, Klaus flirted with Thomas to attract the attention he desperately needed from his formal and distant father. As an adult, he acted out Thomas’ homosexual desires and fantasies. Thomas’ erotic fantasies were both narcissistic and quasi-incestuous. He was strongly attracted to the idea of incest. In Song of the Little Children (1918), he exalted the concept and declared that “incest could be seen as a highly refined version of marital love.” In his historical novel The Holy Sinner (1951), Pope Gregory, a child of incest, unwittingly enters an incestuous marriage. But after his first dangerous sexual impulse, Thomas had to keep Klaus at a safe distance. As Klaus grew up, he had to come to terms with an overwhelming force in his own life as well as with a writer of genius and mythical public figure. Thomas’ patrician background and dignified appearance, his forceful character and fame as a writer, the adoration he received from his wife and servants, inspired awe and reverence in Klaus. In their upper-class and extremely rigid household, the children remained remote from their parents. They had a separate nursery and were mainly brought up by nursemaids, governesses, and tutors. Their father was exceptionally withdrawn except for a brief hour or so each day when they fiercely competed for his interest. Handsome, intelligent, and successful, Klaus was also disturbed and tormented. Like Thomas, Klaus went into exile when Hitler took power and became active in anti-Nazi politics. He edited the highbrow magazines Die Sammlung (The Collection) in 1933, an exiles’ journal published in Holland, and Decision in 1940. Thomas, hoping to protect his valuable Munich house and possessions and unwilling to publicly oppose the Nazis in 1933, refused to write for Die Sammlung, but he did publish in the wartime Decision. Klaus reported on the Spanish Civil War, and Thomas was proud that his son served in the psychological warfare branch of the U.S. Army. Klaus wrote several novels, most notably Mephisto (1936), based on the spectacular career of the pro-Nazi actor Gustaf Gründgens, his lover and Erika’s sometime husband, who was patronized and protected by Hermann Göring. He also published his autobiography, The Turning Point (1942), which celebrated his homosexual heroes with biographies of “Mad” King Ludwig of Bavaria, Peter Tchaikovsky, and André Gide; and he adopted Jean Cocteau as his mentor. Christopher Isherwood, who knew Klaus in the louche precincts of Berlin and Los Angeles, observed the contradiction between his apparent and real character: “On the surface, as always, Klaus was bright, witty and seemingly interested in what was going on in the world around him. He had a lot of courage and he tended to keep the melancholic side of his nature hidden. … He felt, with an extraordinary intensity, the sadness and cruelty of life.” Like Adrian Leverkühn in Thomas Mann’s Doctor Faustus (1947), Klaus committed a series of Faustian transgressions. Heilbut wrote that “Klaus’ characteristic blend of voyeurism, narcissism, melancholy and nostalgia is a self-consciously decadent, if not campy, variation on his father’s themes.” Klaus described himself as a hooked fish and admitted that his provocative and scandalous behavior made Thomas, always keen to protect his dignified image, deeply ashamed: “Having begun my career in his shadow, I wriggled and floundered and made myself rather conspicuous for fear of being totally overwhelmed. … What I failed to realize was the amount of embarrassment my eccentricities caused my father.” It’s hardly surprising that Thomas, ignoring his own responsibility for Klaus’ problems, strenuously disapproved of the adult son for whom he’d had such high hopes. Thomas portrayed Klaus as a rebellious teenager who defies his respectable father in his autobiographical story “Disorder and Early Sorrow” (1925): “Bert is blond and seventeen. He intends to get done with school somehow, anyhow, and fling himself into the arms of life. He will be a dancer, or a cabaret actor, possibly even a waiter—but not a waiter anywhere else save at Cairo, the night-club, whither he has once already taken flight, at five in the morning, and been brought back crestfallen.” Thomas assumed his characteristically ironic attitude toward his precocious, impatient, and ambitious son (“crestfallen” suggests sexual dysfunction), who recklessly flung himself into life and became a famous, worldwide cabaret actor. Later on, W. H. Auden thought Klaus was “wasting his life in New York, pretending too much and achieving too little.” Thomas confirmed this judgment by telling Klaus: “For a long time people did not take you seriously, regarded you as a spoiled brat and a humbug; there was nothing I could do about that.” Thomas, a self-absorbed deity with an artist’s overwhelming ego, was completely absorbed in his work and habitually treated Klaus with benign neglect. Klaus wrote that his father maintained a similar attitude toward both his son and his fictional characters: “observant irony, half-amused, half-skeptical; indulgent, understanding and moderately curious as to what was going to happen next.” Thomas, who was often alarmed about impending disasters, couldn’t possibly approve of a son who was financially dependent on his parents throughout his adult life—as well as a homosexual and a drug addict. As Klaus wrote in his diary: “I perceive, again, very strongly and not without bitterness, [father’s] complete coldness to me. Whether benign, whether irritated (a very curious kind of ‘embarrassment’ at the existence of his son): never interested, never engaged in any real sense with me.” Klaus had to endure his frightening father’s intimidating silence, severity, irritation, and anger. Klaus defined his own identity as a writer in relation to his father. His literary efforts were inevitably criticized by reviewers either for exploiting Thomas’ famous name or for failing to equal his titanic achievement. In Klaus’ memoirs, he is torn between veneration and rivalry, between a desire to bask in his father’s greatness and to reveal his human failings. He took care to conceal the cracks in the family façade and never managed to explain why he felt crippled, even crushed, by his father’s overwhelming presence and leadership of the anti-fascist exiles. It seemed expedient, Klaus wrote of himself in the third person and with a significant proviso, “to exploit his father’s prestige and contacts. But his vanity, or his sense of honor, prevented him from doing so—at least, for a while.” The anti-Nazi context of Klaus and Erika’s memoir, Escape to Life (1939), demanded a dignified and flattering portrait of Thomas as leader of the German emigration. But there were some hints, between the lines, of his repressive power and godlike authority at home. They recalled that they seldom saw their father, who demanded absolute quiet during his morning work hours and when he rested and wrote letters in the afternoon. There were “terrible moments” when he suddenly appeared to yell at them for disturbing his writing. They associated him with the vague smell of cigar smoke, eau de cologne, and dust from his books. “He did not seem to trouble his head about us,” they recalled. “He thought it was better to give us ‘a living example’ than to make any attempt to bring us up in the way [he believed]we should go. The atmosphere of our home [had]the feeing of spiritual responsibility, the discipline of work, the regularity of life.” In fact, Klaus rejected these bourgeois values throughout his rebellious and self-destructive adult life. Always eager for his father’s approval and constantly disappointed at not getting it, Klaus sadly confessed: “He never seemed to remember exactly with whom I lived, which book I was working on, or where I had been spending the time since he had seen me last.” The most Thomas could offer, while noting Klaus’ notorious escapades, was a solemn jocularity that seemed to foresee failure: “Good luck, my son! … And come home when you are wretched and forlorn!” Home provided a comfortable refuge but did not offer emotional support. In a key passage, Klaus tries to define himself in opposition to Thomas, but ends by submitting to his profound influence: “I prided myself on being disorderly and eccentric, as my father is punctual and disciplined. I reveled in mysticism, for I thought him a skeptic. … He is by instinct and tradition a Protestant: I was attracted to Catholicism. With the exception of Nietzsche, most of the great men in whose works and characters he took particular interest left me rather cool.” Critical and dismissive, Thomas judged his children with implacable severity, and Klaus sadly affirmed: “It is no easy job to be the child of a genius.” Klaus felt that no matter what he achieved as a writer, he could never (as suggested by the title of his memoir, Escape to Life) escape from his father and live his own life. He agreed with one of Tolstoy’s children, who explained: “Nothing can be worse than being the son of a great man. Whatever you do, people compare you with your father.” Klaus lamented that Thomas “triumphs wherever he goes. Shall I ever get out from under his shadow? Will my strength last so long? In a word, ‘great men’ should certainly not have sons.” Thomas agreed that “someone like me should obviously not bring children into the world.” But these statements meant quite different things to each of them. Klaus meant that he was doomed to be constantly overwhelmed by his father. Thomas meant that his secret sexuality doomed him to produce homosexual misfits. Thomas, the self-styled Goethe of the 20th century, wrote of Goethe’s son August in his novel Lotte in Weimar (1939): “To be the son of a great man is a high fortune, a considerable advantage. But it is likewise an oppressive burden, a permanent derogation of one’s ego.” Thomas’ two sisters and two sons all committed suicide. In July 1910, his sister Carla, blackmailed and then jilted by her lover, took cyanide. Distancing himself from that tragic event, Klaus called it “an exquisitely botched attempt at theater.” In Doctor Faustus Thomas portrayed Carla’s failure as an actress and terrible death. Klaus had survived Nazism, exile, and war, but he seemed to have an unlimited pharmacopoeia that included cocaine, heroin, morphine, opium, and Demerol. Thomas refused to take Klaus’ drug addiction seriously and claimed that his son took morphine only in moderation. Infected with syphilis and poisoned by arsenic treatments, too weak to break his drug habit, the victim of miserable homosexual adventures and beatings from rough-trade sailors, Klaus was alienated from both his parents and from Erika, for whom he had incestuous desires. He was lonely, uprooted and homeless, blocked as a writer, unable to publish his works in Germany, and bitterly disillusioned about conditions in postwar Europe. Klaus made several unsuccessful suicide attempts, and Thomas, though noting his son’s perilous connection to Carla and ignoring his pleas for sympathy, refused to visit him in the hospital. On July 12, 1948, he told Theodor Adorno: “I am somewhat angry with him for having tried to do that to his mother, whose steadfast understanding over the years had spoiled him. … The situation remains dangerous. My two sisters committed suicide, and Klaus has much of the elder sister in him. The impulse is present in him.” In Cannes in May 21, 1949, Klaus finally killed himself with an overdose of sleeping pills, slit wrists, and a gas oven. On the day Klaus died, Thomas, on a lecture tour, placed public duty above family responsibility. He wrote to Alfred Knopf: “In Sweden the tragic news reached us, and our first idea was to give up the whole trip. But eventually I decided to fulfill my lecturing obligations, and I believe this was the right thing to do.” Heilbut explained Thomas’ rather cold, self-protective reaction by stating that either “Klaus’ drug addiction and continual cries for help had exhausted his family, or that the highly ‘theatrical’ gesture (the adjective he used to describe Carla’s suicide) demanded an equally public act of defiance.” In a letter to Hermann Hesse dated July 6, 1949, Thomas gave another, more anguished explanation of his response to Klaus’ suicide: His case is so very strange and painful, such skill, charm, cosmopolitanism, and in his heart a death wish. … My thoughts dwell sorrowfully on his abbreviated life. My relationship to him was difficult, and not without feelings of guilt, for my very existence cast a shadow on him from the start. Yet as a young man in Munich he was a high-spirited prince who did a great many provocative things. Later, in exile, he became far more serious and moral, and truly industrious as well; but he worked with such facility and speed that there is a scattering of flaws and oversights in his books. Who can say when he began to develop the death impulse which was so mysteriously at variance with his surface sunniness, geniality, facility, and cosmopolitanism? Inexorably, in spite of all our support and love, he destroyed himself, for at the end he no longer reacted to thoughts of loyalty, gratitude, consideration for others. Here Thomas begins by admitting feelings of guilt and taking some responsibility for Klaus’ suicide. He then contrasts Klaus’ literary faults with his own hard-earned perfection and confesses that he doesn’t understand the motives for his son’s self-destruction. In their memoir, Klaus and Erika perceptively defined the great theme of Thomas’ work—and of their lives—as “the motive of a love which burns the more unquenchably just because it is hopeless.” Jeffrey Meyers’ 33 books have been translated into fourteen languages and seven alphabets. One of his recent books is Thomas Mann’s Artist-Heroes (2014).