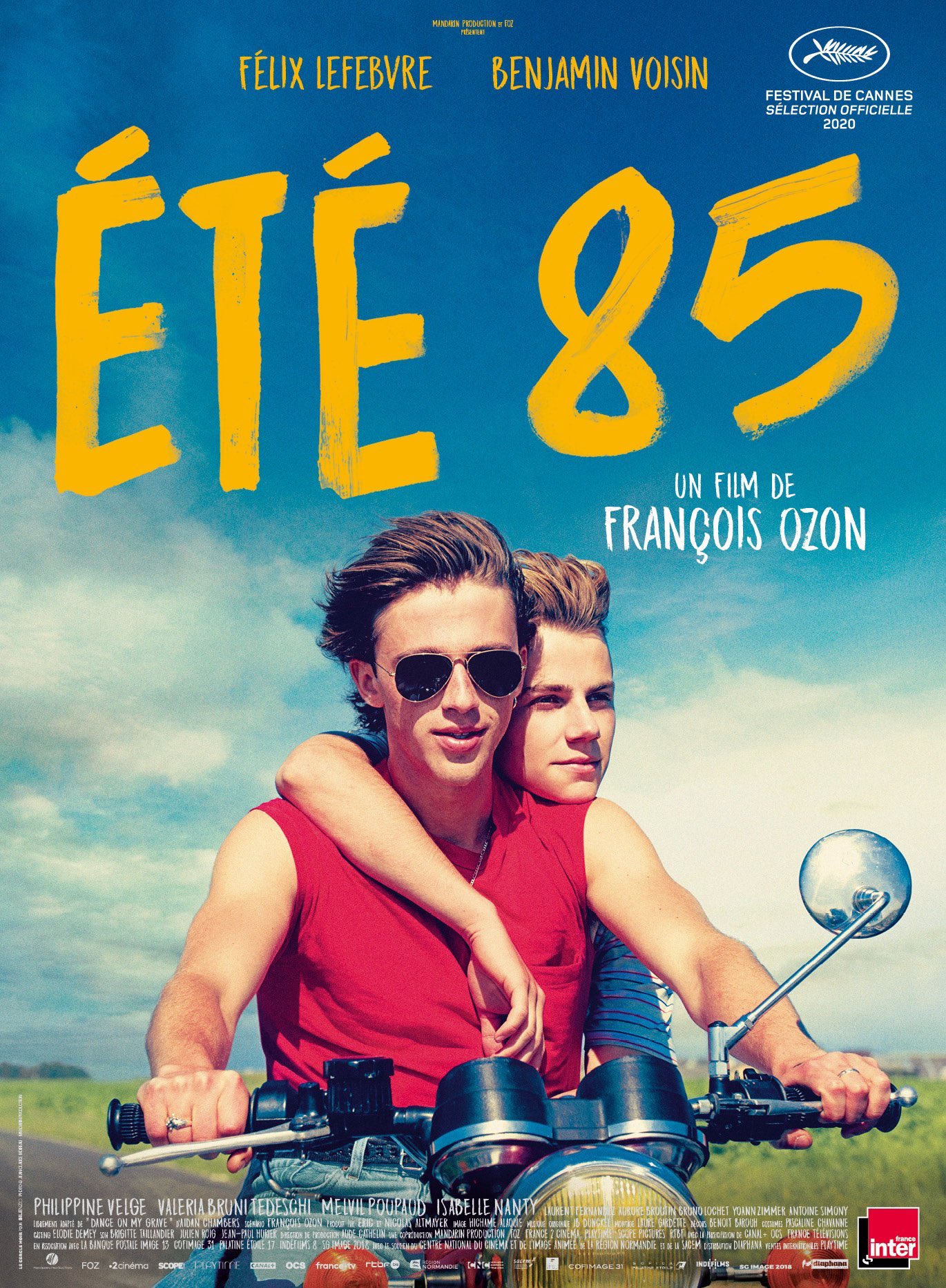

SUMMER OF 85

SUMMER OF 85

Directed by François Ozon

Mandarin Films, et al.

LIGHTLY NARRATED by sixteen-year-old Alex, Summer of 85 is a newly released French film that’s been doing the virtual filmfest circuit during the pandemic. Alex reveals early on that this is a story about his friend David, who’s destined to die before the end of the picture (no spoiler alert needed). This is Alex’ attempt to understand what happened and what role he played in this tragic event.

Directed by François Ozon (8 Women, Swimming Pool), the film could be seen as a “Romeo and Romeo” tale with respect to the youth and foolish passion of its participants and the brevity of their affair, but the tragic ending has nothing to do with clannish loyalties or any kind of social restriction in this tolerant coastal French town in 1985. Quite the opposite: Été 85 explores a kind of life that’s unconstrained by traditional social obligations and quaint notions of duty or loyalty. While Alex continues to adhere to a romantic ideal of “true love,” what he discovers in David is a personality who seems to have adapted fully, and happily, to the anomie of the age, a free spirit who’s able to enjoy the full range of opportunities (especially sexual ones) that come along. Thus if the classic tragedy has a feeling of overdetermination, this modern variation takes a course that often seems arbitrary and unexplained as we follow Alex following David through his shifting whims.

This film will be catnip for those who fancy youthful, sexy love affairs—or the eye-candy actors (Félix Lefebvre as Alex, Benjamin Voisin as David) who enact this particular one. The boys meet at sea when Alex’ sailboat capsizes in a brief storm and David rescues him and his boat.

Director Ozon has seeded the film with enough quirky bits and pieces—David’s mother’s seductiveness toward Alex, an English girl who plays a role in the boys’ epic fight, the sensual beauty of the French Riviera—to keep things interesting. One important plot element turns on an odd pact that David makes Alex agree to early on in the affair: that Alex will “dance on my grave” when David meets his end. We already know that this eventuality is not far off: did he have a premonition? a death wish? But it’s not at all clear why this happy-go-lucky dude is already making funeral arrangements. And why this particular request, and why of Alex, his casual boyfriend of a few weeks? Given the centrality of Alex’ pledge to the plot, this absence of motivation adds to the sense of an arbitrary world—which could be a commentary upon the film’s logic or upon real life as Ozon sees it.

CICADA

Directed by Matthew Fifer and Kieran Mulcare

Beast of the East Productions

THE THEME of tracing a current psychological disorder to a childhood trauma has a long history in cinema, an art form that arose just as Freud was gaining widespread acceptance in the U.S. Hitchcock was the master—think Marnie and Psycho—but the genre has evolved since then even as psychology has moved away from Freud’s notion of repressed memories as ghosts of the unconscious that haunt our adult lives, unseen.

An example would be a new release titled Cicada, which was co-written by Matthew Fifer and Sheldon Brown, who also play the two leading roles. The film bills itself as “part narrative, part documentary,” suggesting that it is deeply autobiographical. Fifer plays Ben, a 27-year-old gay man who’s living with a terrible memory from early childhood that haunts his every interaction with friends, relatives, sex partners, and boyfriends. But the underlying trauma isn’t some repressed memory that’s lost in the mists of time. Ben remembers perfectly well what happened to him—we witness flashbacks of a young boy with long blond hair running happily in a yard—but he just can’t bring himself to tell anyone. Indeed his attempts to tell the story—to a psychotherapist, to his boyfriend, or to his mother—and his inability to do so form the central struggle in Ben’s psychodrama.

Most of what we first learn about Ben involves his very active sex life in New York City: the fact that he’s a top with guys, that he also has sex with women, and that he doesn’t form long-term relationships. Soon enough, however, he meets a man named Sam—while browsing books at the Strand!—and they hook up, start dating, and begin to use the “boyfriend” word. We learn that Sam, who’s African-American, is also keeping a secret—the fact that he’s gay—from a parent, namely his ultra-religious, and clueless, father. We discover that he too is living with trauma, having survived a drive-by gunshot wound in the fairly recent past, which left a nasty scar and what appears to be a colostomy bag.

That both men are deeply damaged by life’s vicissitudes is undoubtedly part of the bond that holds these otherwise improbable lovers together, but it also threatens to drive them apart.

What makes this film work—and it works extremely well—is the intimacy of the connection we experience with both Ben and Sam, whose emotions are raw and filmed at close range. To the extent that Fifer and Mulcare are telling their own story, it seems safe to assume that these guys are not Method acting but reliving the very events that tend to elicit these emotions. This is not to suggest that both men are not terrific actors: achieving this level of authenticity as the cameras are rolling is always an impressive feat.

A word on the title, which refers to the seventeen-year cicada, whose cyclical return is taking place in the year that the movie is set. We learn that Ben’s trauma occurred at the time of the cicadas’ last appearance. (However, somewhat puzzlingly, the blond boy in the flashback looks much younger than ten.) The image of the cicada is generally a menacing one, conjuring biblical plagues, but it can also be, as this film seems to suggest, a symbol of rebirth.