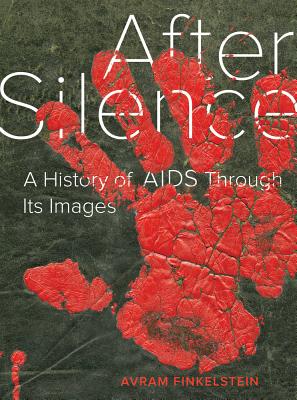

After Silence: A History of AIDS through Its Images

After Silence: A History of AIDS through Its Images

by Avram Finkelstein

of California. 272 pages, $27.95

RENOWNED ARTIST Avram Finkelstein has some blunt warnings for readers in the introduction to his book, After Silence: A History of AIDS through Its Images. For those who don’t immediately recognize his name, you will remember his place in the epidemic: Finkelstein was part of the fiery collectives that created some of the most memorable agitprop images associated with HIV/AIDS activism, including “Silence = Death,” “Read My Lips,” and “Kissing Doesn’t Kill: Greed and Indifference Do.” The images that Finkelstein co-concocted are so engrained that my bet is the words alone evoke them immediately.

But Finkelstein is clear that this “will not be a book about the meaning made of Silence = Death within academia.” Instead, he will favor practice over theory, plans to discuss propaganda more than art, and will get into his role as a creator rather than a scholar. He then dives in, taking us back to 1981, when a mysterious ailment was hitting gay men in New York with devastating consequences. Finkelstein was caught in the crosshairs of the epidemic early on. His passages about his lover are full of heart-wrenching detail. After that loss, the author becomes attached to another man who soon breaks it off, only to commit suicide weeks later. The devastation of the loss is palpable, and Finkelstein perfectly describes the combination of grief and fury that fueled so much of the ACT UP strain of activism and, in his case, the art that went with it.

As well as being a great artist, Finkelstein, as it turns out, is also a brilliant writer. As someone who attended ACT UP meetings in New York in 1988, I can attest to the accuracy of his descriptions of the proceedings. “The room pulsed like a nightclub, blaring with ideas instead of music, or a school you could teach at one minute and attend the next, an ever-expanding life raft for the disinherited.” The meetings were rife with contradiction: frenetic and full of anger and conflict, on the one hand, they were also safe places where people knew they could cry if they needed to, where there was intense solidarity in a shared state of crisis.

As well as being a great artist, Finkelstein, as it turns out, is also a brilliant writer. As someone who attended ACT UP meetings in New York in 1988, I can attest to the accuracy of his descriptions of the proceedings. “The room pulsed like a nightclub, blaring with ideas instead of music, or a school you could teach at one minute and attend the next, an ever-expanding life raft for the disinherited.” The meetings were rife with contradiction: frenetic and full of anger and conflict, on the one hand, they were also safe places where people knew they could cry if they needed to, where there was intense solidarity in a shared state of crisis.

Amid all of this, Finkelstein met with the Gran Fury collective, and they collaborated to concoct some images. The insight into collective creation, where an ensemble of artists works together to create one work, is invaluable. Finkelstein recalls that their main objective was to reach as many people as possible, invigorating the troops while also reaching the uninitiated with their messages. They were creating great advertising, and the fact that the images remain so identifiable and resonant after so much time is testimony to their genius.

There are funny and touching anecdotes along the way, especially if you know the players involved. At one point, Finkelstein and others were discussing having T-shirts made with the “Silence = Death” image on it when an infuriated Larry Kramer screamed out “Sissies! People are dying and you’re talking about T-shirts!” before storming out of the room. After the “Read My Lips” image, featuring two men in Navy uniforms kissing passionately, appeared almost everywhere, Finkelstein got a phone call from an elderly veteran who identified himself as one of the men in the picture. The photo was in fact of two actual Navy officers who were photographed kissing in a gay bar decades earlier. Finkelstein was touched that the man asked for no residuals; in fact, he was pleased that the image was being used to make a positive difference.

Finkelstein’s life of activism and creativity is hugely impressive, and this book is a perfect reflection of that. It is intellectually and emotionally engaging at once, never losing sight of the political history the author is recounting. Finkelstein also reminds us that the HIV/AIDS crisis is far from over, analyzing the work of a new generation of queer activists and their responses to narratives around the plague.

If there is one odd thing about After Silence, it is the title and presentation of the book. It seemed this would be a quasi-academic analysis of various noteworthy images relating to HIV/AIDS. Instead, it really is Finkelstein’s memoir. But if my expectations were upended, my satisfaction was a pleasant surprise.

Matthew Hays, who teaches film studies at Concordia University and Marianopolis College, is the co-editor (with Tom Waugh) of the Queer Film Classics book series.

Those Posters Were Everywhere

0Published in: March-April 2018 issue.