CONVERSION

CONVERSION

Directed by Zach Meiners

Produced by Chronicle Cinema

THE DOCUMENTARY Conversion opens on a black screen with white lettering informing the viewer that 689,000 LGBT adults have gone through “conversion therapy”—indoctrination programs for young people struggling with their sexual orientation that claim they can help them convert from gay to straight. The film’s first images show us driving through a calm suburban neighborhood. In voiceover, Troy Stevenson recounts his meeting up years earlier, at fifteen, behind school with a friend of the same age, holding hands and talking. A group of school footballers catches sight of them and hurls anti-gay slurs. The boys run off to their separate homes and later speak on the phone. Trey’s friend is deeply upset, worrying that if his parents find out, they will send him back to a conversion program he’s already been through once before. He is deathly afraid. Trey plans to speak to him the next day, but he can’t. His friend has committed suicide.

The film that follows is a personal investigation by its director, Zach Meiners, into the world of conversion therapy, a network of programs that go under such names as Exodus International, Love in Action, Opt for Life, and Focus on the Family. Zach is one of the film’s three main subjects. He was a typical youngster who joined the Boy Scouts and soon discovered that he wasn’t interested in girls like the rest of the gang. Next, Dustin Rayburn recalls a boyhood under the disciplinary eye of his father, a pastor and a “man’s man.” Elena Joy Thurston, a woman raised in the Mormon Church, marries at twenty and has four children by age thirty. Through an intense female friendship, she realizes her lesbian inclinations and the depths of her unhappiness.

Each story is told in stages through the course of the film, which also examines the particular hold of conversion therapy in religious communities and its powerful reach through charismatic male leaders like Alan Chambers and Joe Dallas of Focus on the Family, and McKrae Game of Hope for Wholeness. We eventually learn that some of these men resisted their own gay inclinations and used whatever pseudo-psychological expertise they acquired to fashion themselves as “counselors” with a professional-sounding lingo and a well-rehearsed behavioral model known as “reparative therapy.” These tactics impress enough parents who can’t accept their gay kids to get them to throw away their money and enrich these conversion therapy grifters.

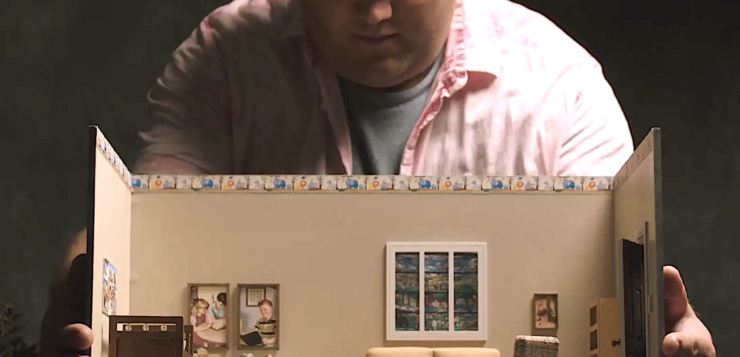

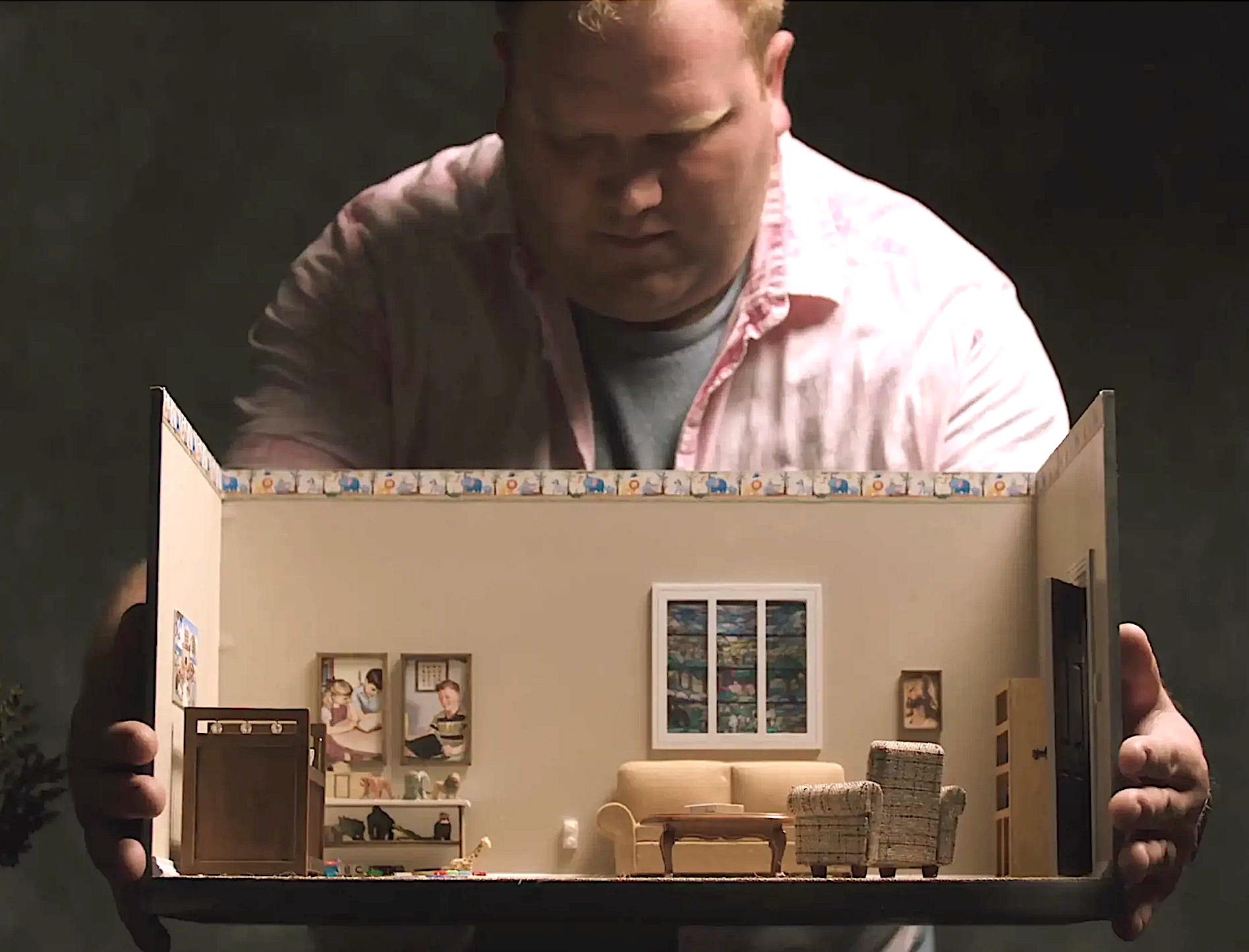

A recurring motif is a series of contemporary model rooms that appear under voiceovers that tell the story of conversion in America (often with little connection to the narrative). The models, like updates of Victorian doll houses, present perfectly proportioned furnishings and decorations: couches, armchairs, conference tables, window frames, and pictures hung on walls. They seem intended to convey an ideal of “normalcy” sought by the pro-conversion warriors, but also operate as a haunting metaphor for the warmth and security sought by Zach, Dustin, and Elena. Occasionally they allude to details discussed in the film, like a shot of a miniature Bible resting on a coffee table, or popular conversion therapy books fleetingly glanced and waiting to be read, such as Joe Dallas’ Desires in Conflict. The miniature rooms are sometimes lit with “sunshine” or “streetlight” through a small window; sometimes the rooms remain dark and somber. In their stately calm, like that in an Edward Hopper painting, these dollhouse rooms evoke an elegiac quality that underscores the film’s vein of sorrow and lament.

Two speakers in the film share their expertise as longtime students of conversion therapy. Wayne Besen is an anti-conversion activist who speaks bluntly about the way in which the “conversion industry” feeds off dubious claims of success at permanently altering anyone’s sexual orientation. Dr. Kelsey Burke, a psychologist who brings a calm but informed analysis to the origins of conversion therapy, places less of the onus on evangelical Christianity and more on the post-World War II upsurge in the practice of psychoanalysis, some practitioners of which went to “great lengths” to re-orient their patients’ sexual orientation, resorting to such practices as electroshock and aversion therapy.

The film’s overall tenor is dour. Dustin Rayburn and Elena Joy Thurston locate key moments in their sexual development as children in the experience of a rape to which each was victim. But if Dustin and Elena’s stories eventually lead to separate epiphanies—with Dustin fleeing to construct a fresh professional drag identity in New York City, and Elena leaving her marriage, and the Mormon Church, to create a strong bond with another woman—Zach Meiners’ life doesn’t come to such a certain or cheerful resolution. Family photos show a sweet and sparely built youngster, while the adult Meiners, now stocky and soft-spoken, speaks of how in his teenage years he descended into depression and suicidal ideation. He concludes that conversion “tears a person down.” Discovering that McRae Game, his counselor from years prior, has come out as gay, Meiners interviews him for the film. In the cadences of a Southern preacher, Game recounts his considerable success at conversion, yet he was fired from his post for addiction to gay porn.

Meiners’ making of Conversion is in part his own personal reckoning. He, like his companion subjects, tries to dig down into the depths of confusion, hurt, and trauma that marked their psychological imprisonment in conversion therapy. Ultimately, Meiners knew that he “couldn’t change.” He is at least comforted by the apology his father offered in the fall of 2019. The documentary that he has fashioned will not, I suspect, comfort many viewers. Anti-conversion activist Wayne Besen assures us near the film’s end that, despite the success of some legal conversion bans that have been passed, these programs are “staging a comeback.” Religiously sanctioned programs are constitutionally protected, online therapeutic sessions are unregulated, and Christian media have intensified their outreach to their own populations. Given the current climate, Conversion serves as a dreadful warning.

Allen Ellenzweig, a longtime contributor to these pages, is the author of George Platt Lynes: The Daring Eye (Oxford Univ. Press, 2021).