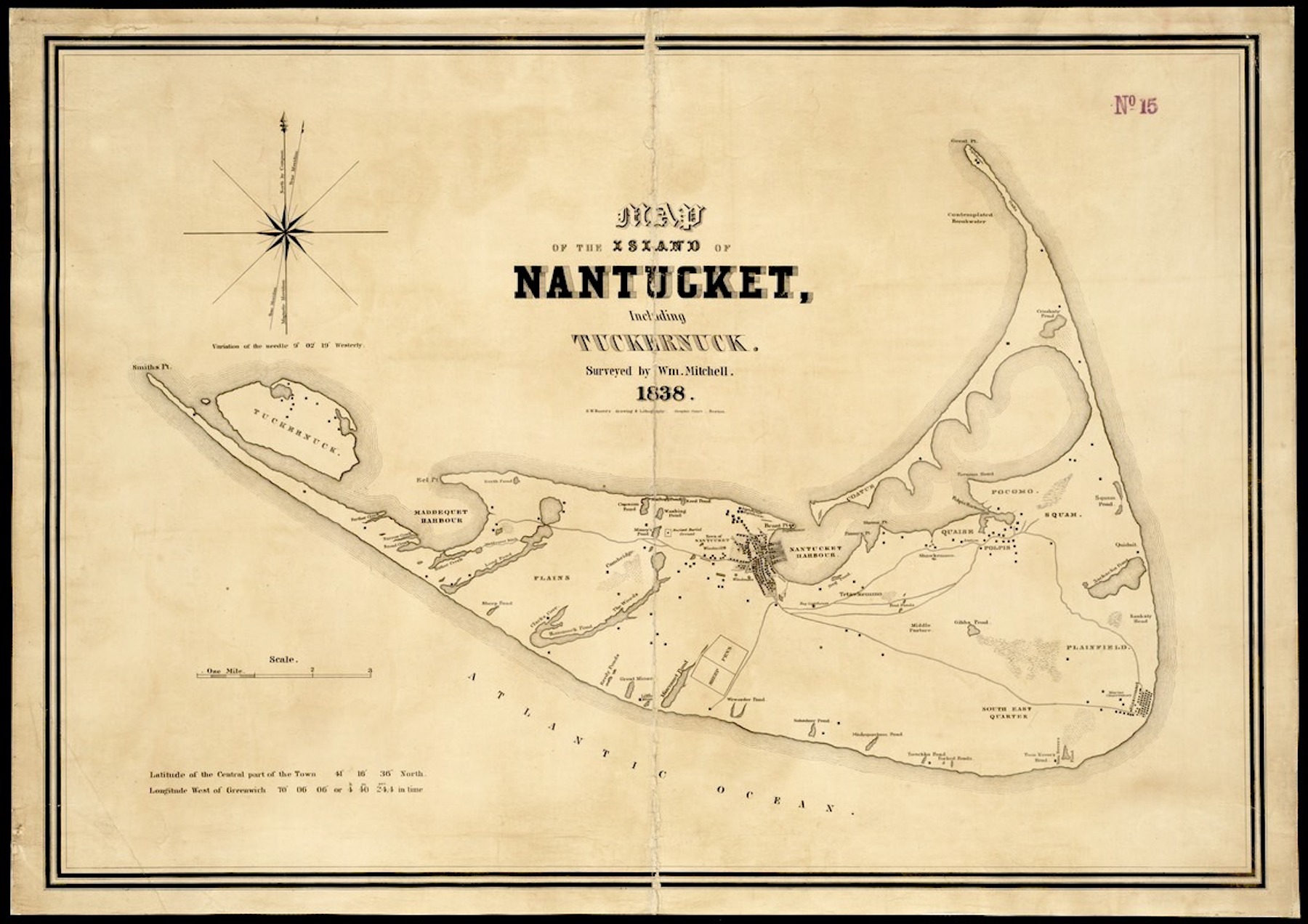

WHERE THE SKY MEETS THE SEA off the coast of Cape Cod, there was once an island where guests could drop their clothes and their inhibitions in a men-only paradise of Zen-like simplicity and muscular homoeroticism. The island of Tuckernuck (Algonquin for “loaf of bread”) still exists, and may be reached by a short jaunt from Nantucket, but the part of the island where naked gentlemen once romped disappeared under the waves a century ago, as irrecoverable as Camelot.

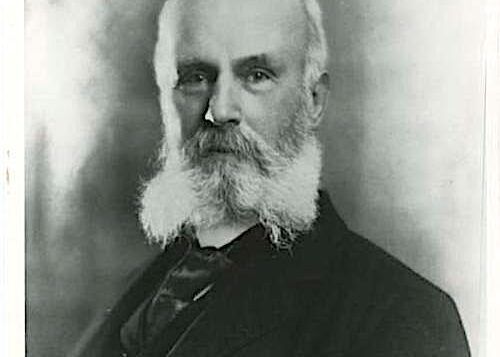

In 1871, prominent Boston surgeon Henry Bigelow built a summer home on the west end of Tuckernuck Island, a home he called “Tuckanuck” (spelling the name of the cottage the way the locals pronounced the name of the island itself). The building was rustic and isolated, without indoor plumbing or gaslight, but sea breezes provided a welcome break from Boston’s stifling summer heat. The home was eventually inherited by Henry’s only child, William Sturgis Bigelow, who set about turning it into a summer retreat for a very different sort of family.

Young Sturgis had been coerced into following his father and grandfather into the field of medicine and earned his M.D. from Harvard, though he found medical practice in general—and surgery in particular—distasteful. Fortunately, he had inherited a substantial fortune from his mother, which freed him to abandon medicine and follow a newly acquired passion: collecting Japanese art. During an extended visit to Japan (1882–1889), Bigelow became enamored of all things Japanese and began collecting the artifacts that were being jettisoned during the Meiji period’s rush to westernize. His efforts to preserve traditional Japanese culture earned him the Order of the Rising Sun, a rank of honor, from a grateful Emperor Mutsuhito.

Bigelow eventually amassed over 26,000 objects (including “aristocratic erotica”) which he donated to Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts, establishing it as the finest collection of Japanese cultural artifacts outside of Japan. He converted to Tendai Buddhism, at times donning the robes of a Buddhist monk, and he proselytized on behalf of Eastern beliefs and practices—an eccentricity that raised eyebrows among Boston’s stern Puritans and cerebral Unitarians. Bigelow never entirely abandoned Beacon Hill (where he continued to live when not on Tuckernuck), but he repudiated its notion that “the Lowells speak only to the Cabots, and the Cabots speak only to God.” He welcomed visitors to his island regardless of their family background; they needed only be entertaining, creative, male, and discreet. He could not, however, completely escape his heritage as scion of what was approvingly known as Old Money. Deeply committed to Buddhism, Bigelow “emanated a peaceful radiance,” his friend Margaret Chanler once observed, but a radiance “mingled with a faint fragrance of toilet water.” When not in monk’s robes he preferred expensive Charvet neckties and bespoke suits from Saville Row. His commitment to Japanese culture was sincere, though, and not merely cosplay. At least not entirely cosplay.

On Tuckernuck, Sturgis Bigelow created a retreat that was a cross between a Buddhist monastery, the Plaza Hotel, and Hemenway Gymnasium at Harvard. There was no electricity or running water, and everything needed to be ferried over from Nantucket or the mainland, but the food and wine were excellent, the service impeccable, and the accommodations comfortable if spare. On the second floor of the large cottage, reached by a steep and narrow stairway that one guest compared to a companionway on a ship, there was a series of small monastic guestrooms, “scrupulously clean; just furniture enough in each to supply one’s needs; exceptionally comfortable beds with linen exhaling a countrified freshness; white walls of wood; white rafters overhead; all visible and all spotless to the peak of the roof.” Sets of French doors opened onto a shared loggia.

Amenities were basic but tasteful. A separate bathhouse lacked plumbing, but could comfortably accommodate multiple men performing their morning ablutions together. In the communal lavatory, guests found “a row of white china wash bowls, one for each guest, set at a convenient height for shaving, and a little shelf above with a row of soap dishes containing Pears’ soap, also bottles of Pears’ Lavender Water, French shampoos and other lotions and shaving creams.” Bigelow provided his guests with a library of over 3,000 volumes, including erotica in both French and German. A wide veranda was furnished with hammocks and lounge chairs for reading, and a telescope for anyone curious enough to want to scan the horizon. For recreation there was a tennis court, a shooting range, a Japanese soaking tub, and a pole for “tethered-ball.” On one part of the island was a small forest of scrub oak where gentlemen might wander for intimate encounters. And always there was the surf crashing on Sturgis Bigelow’s private beach.

But the feature that set Tuckanuck apart from other retreats was its dress code: as soon as gentlemen arrived on the island they were urged to remove their trousers. What they wore instead is most frequently described as “pajamas,” though the loose garb is also referred to as a Japanese kimono or a Greek-inspired chiton. When swimming or exercising, or merely lounging in the sun, clothing of any kind was optional. For many men, nudity came to define a visit to Tuckernuck.

Bigelow’s guests came primarily from Boston, New York, or Washington, D.C. “Sturgis Bigelow, MD,” wrote Thomas Russell Sullivan to a friend, “has come in with hypnotic influence and carries me off to dine with him tonight, seductively, with the resident literati and tutti fruiti [of Boston].” Among the many tutti fruiti in Bigelow’s immediate circle was Sullivan himself, a gay playwright best known for his stage adaptation of Robert Louis Stevenson’s The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. Sullivan was a frequent guest on Bigelow’s island, writing in his journal in 1896: “At Tuckernuck, living independently in the open air, playing golf and tennis, bathing in the magnificent surf without hampering garments, to dry in the sun like a seal, afterward, on the warm sand.”

Sullivan’s housemate (and sometime lover) in Boston, Theodore Dwight, was chief librarian at the Boston Public Library, and privately amassed one of the largest collections of homosexual pornography in the country. Dwight trained himself in photography in order to capture his own images of male nudes. Most of his models were burly Boston Irish, though he had a particular penchant for Italians (his barber would provide him with likely liaisons). Tuckanuck was furnished with its own darkroom where Dwight could have developed and printed shots of his fellow guests, though if he ever captured such souvenirs, they have yet to be uncovered. Included in Sullivan and Dwight’s charmed circle was Canadian poet Bliss Carman, whose poem “The Bather” may be describing a visit to the island: “I saw him go down to the water to bathe;/ He stood naked upon the bank. … / His legs rose with the spring and curve of young birches.”

When visiting from Washington, D.C., gay writer Charles Warren Stoddard was Bigelow’s frequent guest, both in Boston and on the island. Stoddard provided a memorable description of his arrival on Tuckernuck: “A skiff transported us to the dock, where the butler and the cook in white raiment awaited us. At this moment a tall figure clad in paijamas [sic]appeared at the top of the stairs that led from the dock to the plateau above. He descended with the air of an Eastern potentate, and gave us welcome with Oriental grace.”

Not all of the doctor’s guests were impressed by the languorous pace of Tuckernuck, however. After years of urging his longtime friend Theodore Roosevelt to visit, Bigelow finally convinced the president to accept his invitation, and in 1905 the exhaustingly alpha T.R. stormed onto the island with his entourage. Finding no pleasure in its refined atmosphere of dolce far niente, the president spent only one night and then charged off the next morning. Bigelow was able to introduce Roosevelt to jiu-jitsu, though, and the president eventually earned his brown belt while in the White House.

The Golden Boy of Tuckernuck Island was the poet George Cabot Lodge, known to everyone as Bay. The son of Senator Henry Cabot Lodge of Massachusetts, Bay was an impressionable fifteen-year-old when Bigelow returned from his extended stay in Japan. The elder Lodge and Bigelow had been close friends since childhood, and when Bay met his father’s old comrade he immediately fell under Bigelow’s spell. “Dokko” provided the sensitive young man with an alternative to the bruising life of politics and commerce in which the Cabots and Lodges thrived, and Bay quickly adapted elements of Buddhism to his personal philosophy. For many summers the Senator and his son split their time between the city and the “male paradise” of Tuckanuck. From a steamy Washington, where he was working as the Senator’s secretary, Bay wrote to Bigelow: “I suppose I am here for about three weeks more—and then, with your permission, kind Sir! Surf, Sir! and sun, Sir! and nakedness!—Oh, Lord! how I want to get my clothes off—alone in natural solitudes. In this heavy springtime I grow to feel exquisitely pagan.”

Even after he married Elizabeth Davis in 1900 and the couple had three children, Bay Lodge took every opportunity he could find to escape to Tuckernuck, alone, or with his father or a friend. (The Lodges were welcome to use the cottage even when Bigelow himself was not in residence.) From the island Bay wrote to his wife about his holiday with playwright Langdon Mitchell: “I lead a sane and hygienic life. We go to bed before twelve, and sleep all we can. We breakfast, read, write perhaps an occasional letter, talk for long, fine, clear stretches of thought, and regardless of the time, play silly but active games on the grass, swim, bask in the sun, sail, and talk, and read aloud, and read to ourselves, and talk, and talk.”

§

Given the number of literary guests who gathered on the island over the years, and the almost mythic status that Bigelow’s summer retreat held for homosexual writers (Charles Warren Stoddard called it “Tuckernuck the fabulous, the forbidden”), it’s not surprising that the place found its way into fiction, with attempts to capture the ambience of a private space created for the exclusive pleasure of men who represented a wide spectrum of sexual orientations. Perhaps the most evocative fictionalized version can be found in the novel The Last Puritan, by George Santayana (born Jorge Ruiz de Santayana y Borrás), which was begun in 1891 but not published until 45 years later. Santayana was embedded in the homosexual coterie that Thomas Russell Sullivan referred to as “Boston’s tutti fruiti,” and while he insisted that in his novel about what he termed “erotic friendships” all of the characters were merely composites of people he’d once known, one of the protagonists, Dr. Peter Alden, is clearly based on Dr. William Sturgis Bigelow. Instead of living on an island similar to Tuckernuck, Alden sails from place to place on a private yacht that he has named Black Swan, a vessel small enough to be operated with a minimal crew to assure his privacy, but large enough to accommodate part of his collection of Japanese art and antiquities.

The fictional doctor’s closest companion on his voyages is his captain, a handsome young man named James Darnley, known as Lord Jim. Darnley had been a midshipman in the Royal Navy, but he was court-martialed due to a serious transgression—unnamed, but one that’s described as being common among British schoolboys. At schools such as Eton, Darnley complains, his misconduct would have been dealt with more discreetly to avoid public scandal. Now Lord Jim has been placed in complete control of the Black Swan, plotting its course, steering the ship through tides and tempests, and administering the nightly morphine injections that the doctor requires to stupefy himself to sleep.

Unlike Sturgis Bigelow, Peter Alden in the novel decides to marry, albeit reluctantly. When an associate suggests that his daughter might make a good wife for Alden, the doctor contemplates the proposition with no great enthusiasm: “As to actual love, and all that, she’s a fine female, almost as fine and vigorous as a young male; a little passive, a little sad; somewhat like a blond athlete past his prime, and grown a bit fat, soft, slack and sleepy.” The chief reason for the marriage (plot-wise) is to produce a son and heir: Oliver Alden, the “last puritan” of the novel’s title. Having provided the required heir, Dr. Alden abandons his family and withdraws to his yacht. He has little to do with his son until Oliver is a high school student, at which time he decides to pull the young man into his peripatetic life aboard the Black Swan. The relationship closely parallels that of Sturgis Bigelow and Bay Lodge, as Bigelow was unmarried and childless until he virtually adopted Bay during Lodge’s teenage years.

George Santayana was a professor of philosophy at Harvard and in this, his only novel, he halts the narrative repeatedly for long philosophical disputations delivered as internal monologues or as authorial asides, analyzing the ethical conundrums presented by the twisting plot. Yet throughout the novel, there are also passages of intense homoeroticism that glint like the flashes of sunlight on Tuckernuck’s tidal pools, brilliantly illuminating for just a second, and then gone. Most center on young Oliver Alden. The first evening that Oliver is aboard the Black Swan, anchored off shore, the captain suggests a swim, but Oliver begs off, explaining that he has not brought a bathing suit. “Good Lord,” Jim replies, “you don’t want a bathing suit here. This isn’t one of your damned watering-places with a crowd of old maids parading along the front, and if there’s anyone in the village with a spy-glass, that’s their own affair. Just throw your things anywhere. The boy will look after them.” Oliver hesitates, embarrassed and yet intrigued, but Jim

had undressed in an instant—for to Oliver’s surprise he wore no underclothes—and was vigorously swinging his arms and expanding his chest, evidently in preparation for diving. What a chest, and what arms! While in his clothes he looked like any ordinary young man of medium height, only rather broad-shouldered, stripped he resembled, if not a professional strong man, at least a middle-weight prize-fighter in tip-top condition, with a deep line down the middle of his chest and back, and every muscle showing under the tight skin.

Later, after an evening spent ashore, the two men are returning to the yacht in a small launch when Oliver presses against his new friend: “At any rate, how assuring to lean here against an honest unpretending comrade and feel the weight and firmness of that friendly body, like a wall of strength. How perfectly, too, Lord Jim had behaved that evening, looking so particularly smart and handsome in his dinner-jacket, with his high complexion and thick hair—such an image of youth and soundness and simplicity.”

Oliver was given his own berth aboard the Black Swan, but after a few days he moves into the captain’s cabin instead. “The sound of Jim moving about or whistling and humming in the bathroom had been pleasant to him, and sometimes the two had long talks in the dark, from bunk to bunk, concerning all the secrets of earth and heaven.”

As their friendship deepens, Jim seems to be sending coded messages to Oliver: “‘Odd, isn’t it?’ Jim went on, not receiving any reply. ‘I suppose people aren’t ashamed of doing or feeling anything, no matter what, if only they can do it together. And sometimes two people are enough.’”

The two young men separate, but meet up months later at a Harvard-Yale football game. They talk about what the future might hold for them, and Lord Jim suggests that Oliver will never meet a woman and get married—except perhaps out of a sense of obligation or family duty. “‘Of course,’ [Oliver] went on aloud, blushing a little because unaccountably he remembered the first time he had undressed in Jim’s presence, on the deck of the Black Swan, and how silly he had been about it, ‘of course I shall get married some day.’”

This dance about their sexual attraction to one another continues throughout the novel, never resolved. After years apart, they run into each other on an ocean liner sailing from England to New York, and jostle playfully: “It was like a gambol of schoolboys or of puppies: though taller by two or three inches, Oliver felt like a stripling matched against a man’s strength; and something feminine in him found pleasure in prolonging a resistance which he knew would be overborne.”

As to Santayana’s own sexual orientation, to an interviewer he revealed that, looking back on his years as a Harvard student, he felt he was probably “homosexual” at the time, though unaware of it. In the poems he wrote as an undergraduate, it’s clear that he felt strong emotional and physical attraction to some of his fellow students, but it appears that his sexual development was stalled at an immature stage, which he labeled as “wet dreams and the fidgets.” Of the long, perhaps celibate, years that followed, Santayana would say only that without the “golden light of diffused erotic feeling falling upon it, the world I have been condemned to live in most of my life would have been simply deadly.” And perhaps that diffused, golden erotic light was enough. In The Last Puritan, Santayana writes: “There was a subtle satisfaction in hiding in the open, and feeling what a deep secret might lie hidden in things perfectly innocent and published to the world. You might lead a double life without duplicity; indeed, you must, if you had any inner life at all; for about the important things you always had to be silent.”

§

Santayana’s novel, in which hymns to the beauty of male bodies are scattered among high-minded philosophical discussions, may be an apt corollary to summers on Tuckernuck. There, men of differing social backgrounds and from all gradations along the Kinsey scale found a place where they could stand naked before God and everybody, free to grin or to gawk or perhaps even to grope (if done discreetly, and always by mutual consent). Bigelow made sure there was a careful balance on Tuckernuck between hedonism and decorum, between refined taste and boyish rough-housing, with each man allowed (within limits) to behave as his nature prompted him. The only inviolable rule on Tuckernuck was that one dressed in black tie at dinner.

Charles Warren Stoddard wrote of an evening on Tuckernuck that in many ways encapsulates the spell that Sturgis Bigelow was able to cast, Prospero-like, on his enchanted isle. The host had retreated outside to meditate alone, as he did every evening after dinner, and his guests were lounging around the cottage in dinner jackets, reading or perhaps smoking pipes and sipping aged cognac—a scene that belongs in a Merchant-Ivory film. Suddenly Bigelow appeared in the doorway and called out: “Let us botanize!” In his hand he held an odd flowering tree branch, which he carried over to one of the tables and placed in a vase, bathed in a golden pool of lamplight. The gentlemen gathered around in wonder. “The petals were enormous and of unusual pattern,” Stoddard recalled, “the edges barbed and fringed, the centre embellished with arabesques. Sometimes they seemed to us like bits of rich brocade or tapestry, sometimes like panels of stained glass with the sunshine streaming through; again they were emblazoned with jewels; always more beautiful than pen can paint.” What was it, they wondered—a type of mimosa, perhaps? And then one of the flowers began to move. And then another. One by one the blossoms rose up from the branch and began to flutter around the room. “[T]he air was filled with butterflies balancing daintily upon the wing, lighting here and there for a moment and then flitting again. Finally, for their own sakes, we guided them to open doors and windows and they disappeared in the night. All that was left to us was the memory of something fairylike and hardly to be believed.” The gentlemen in their black ties and their starched shirt fronts, with their sore muscles and their sunburned noses, knew that they had shared a moment of pure magic.

In August 1909, Henry and Bay Lodge were staying on Tuckernuck in Bigelow’s absence. Bay, though only 35 years old, had been experiencing heart arrhythmia for some time, and the family hoped a long rest on the island might cure him. But he suffered an acute case of ptomaine poisoning after eating a tainted clam, and the rigors of the attack proved too much for his weakened heart. He died in his father’s arms.

With the death of the Golden Boy, the idyll of Tuckanuck came to an end. Bigelow closed down the house immediately and did not reopen it for the 1910 season. For years he had been watching the sea slowly eat away at the property and had recorded the relentless disappearance of his safe haven. In 1904: “very heavy surf … 6 to 10 feet cut off the bank.” Then: “The last of the road around Robert’s lot went, leaving about a foot to squeeze by on.” And finally, in 1909: “About 70 feet of bank cut off. Charley Brooks gives it eight years to the corner of the tennis court. I guess six.” When Bigelow died in 1926 he left the property to the La Farge family. The sea continued its relentless assault until, nearly two decades after acquiring Bigelow’s estate, the La Farge heirs relocated his library collection and parts of the house to another part of the island and demolished what remained.

Today the whole of what was once Sturgis Bigelow’s private retreat is submerged beneath Nantucket Sound. On Tuckernuck, piping plovers and roseate terns still cry overhead, salt-spray roses still bloom among the seagrass, and waves still eat at the shoreline, changing its contours with every storm. Bright stars crowd the night sky as the wind rustles dead leaves along the deserted paths of the oak forest. Nothing hints that once there was a special island where, on a warm summer evening, gentlemen in black tie chased butterflies by lamplight.

References

Reed, Christopher. Bachelor Japanists: Japanese Aesthetics and Western Masculinities. Columbia University Press, 2017.

Santayana, George. The Last Puritan: A Memoir in the Form of a Novel. Scribner’s Sons, 1936.

Shand-Tucci, Douglass. Boston Bohemia, 1881-1900. University of Massachusetts Press, 1995.

William Benemann is the author of Unruly Desires: American Sailors and Homosexualities in the Age of Sail, and Men in Eden: William Drummond Stewart and Same-Sex Desire in the Rocky Mountain Fur Trade.