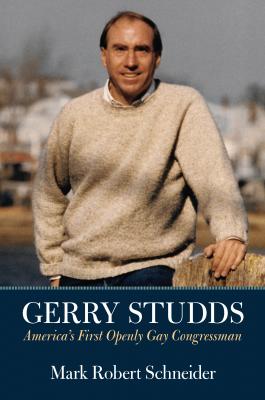

Gerry Studds: America’s First Openly Gay Congressman

Gerry Studds: America’s First Openly Gay Congressman

by Mark Robert Schneider

UMass Press. 296 pages, $29.95

GERRY STUDDS, who served in the U.S. House from 1973 to 1997, might have been just another in a long line of reputable representatives from Massachusetts, were it not for a relationship with a Congressional page in 1983. That brief fling eventually resulted in Studds being outed as gay and censured by the House for diddling the page. But it was the spark for a speech on the House floor in which Studds acknowledged being gay—a first in the U.S. Congress. By using the speech as an opportunity to talk about being gay as an elected official and in general in a society rife with anti-gay prejudice, he helped to launch a national discussion about a hitherto silent minority.

Gerry Eastman Studds (1937–2006) was born in Mineola, New York, and grew up mostly in Massachusetts, where he might have been mistaken, having attended Groton and Yale, for a descendant of old-line Yankee stock. In fact, he was descended from families of Virginia and Tennessee, and the fact that his father was named for Elbridge Gerry had more to do with the marriage of obscure relatives than with blue blood.

Although this book focuses on his career in the U.S. House, some of the less well-known aspects of his life—such as his job at the U.S. State Department, his work on Sen. Eugene McCarthy’s presidential campaign, and as a history teacher—are covered as well, and help explain where some of his later interests in international relations came from. The author has included many well-chosen anecdotes to spice up the story, such as the objection raised by a school principal when Studds gave students some books to use in class: “Reading is a recreation. I will not have it in my school.”

Reading and learning were part of his nature. When he began serving in Congress, he astonished one segment of his constituents by speaking to them partly in Portuguese—their first language and perhaps his fourth. He had even gone to the Azores, where many of the Massachusetts families in his district came from, and to Portugal to practice the language. This love of learning resulted in respect from members of Congress in both parties, who viewed him as one of their most intelligent members.

Embedded within this narrative of a Congressional career is the tale of the scandal that rocketed Studds to national fame. This involved his tryst with a Congressional page. As scandals go, this one was in a sense a technical foul. The page was of legal age and hadn’t the slightest objection to the experience. The issue was one of power imbalance and rules of the House. Studds chose the high ground in his response, recognizing in his floor speech his breach of duty to an employee of the House while refusing to be ashamed of being gay. One of the less well-known aspects of the case is that Studds chose not to have a formal hearing on the charge, because he did not want to cause more harm for the page and others involved. The contrast with his fellow censuree, the straight Phil Crane of Illinois, whose groveling to the House did not play well anywhere, was apparent the next time Studds went home: he was greeted by standing ovations at his next two local meetings.

The scandal is also the tale of the page himself, named only as Page X in the book. The page wanted nothing to do with damaging Studds—he liked the politician and, in an only-in-gay-America moment, turned up later as his “nameless” driver during the subsequent campaign. No one knew who he was, because he had never been named in the report, and Studds never used his presence to advantage during the campaign. At one point, when Studds’ opponent bizarrely struck the Congressman in a hallway, the beefy 27-year-old X shoved the opponent up against a wall. That fall, the voters made a similar decision, keeping the now openly gay representative in office with an unexpectedly strong 59 percent of the vote. Studds won, apparently on the strength of his first-rate service to his constituents rather than on his sexual orientation.

Studds the Democrat made a Republican fishing friend in Rep. Don Young of Alaska, with whom he worked on major legislation affecting the nation’s two largest fishing industries. One of these bills was jokingly referred to by both men as the “Young-Studds Act,” a name their joint softball team adopted and which was reminiscent of his first race, when the simple “studds” bumper stickers became popular with drivers who cut off the last two letters. (For the record, his district included the town of Gay Head, whose name has since been changed to Aquinnah.)

Studds was an exceptionally erudite, effective, and witty speaker (check his on-line videos). In the 1984 race, a finger-wagging constituent tried to shame him with the language of Leviticus, to which he responded that he was surprised to hear the gentleman cite a verse prohibiting the eating of shellfish at a lobstermen’s political meeting. He was also a “pescador” and lobsterman who had his own boat. One of the humorous moments in the book tells of Studds being pulled over at sea by a Coast Guard smuggling patrol, who were astonished to find the chairman of the Coast Guard and Navigation Subcommittee hauling up his own lobster pots.

He was well known for his work on maritime issues and also for trying to pry the truth about the Iran-Contra affair and other Central American scandals out of administration officials (“our founding fathers did not maintain bank accounts in the Cayman Islands”). Schneider’s book covers these accomplishments in detail. His greatest work for the gay community, besides existing, may have been on AIDS issues, especially his decision to send out a copy of Surgeon General Koop’s controversial report on how to battle the epidemic. Having run into various brick walls while trying to work inside the Reagan administration, he simply sent a copy of the report to every household in his district—all 268,000 homes—in effect releasing the contents from political limbo and forcing a discussion of the issues of sex education and condom use that had been suppressed by squeamish politicians.

Studds was able to marry his partner Dean Hara two years before his unexpected death at 69. The young teacher who was not allowed to bring books to class had read himself into history yet again.

Alan Contreras is a writer and higher education consultant who lives in Eugene, Oregon.

Turn the Scandal Around

This is a premium subscriber article. If you are already a premium subscriber and are not seeing all of the article, please login. If you are not a premium subscriber, please subscribe for access to all of our content.

This is a premium subscriber article. If you are already a premium subscriber and are not seeing all of the article, please login. If you are not a premium subscriber, please subscribe for access to all of our content.

0

Published in: March-April 2018 issue.