Somebody to Love: The Life, Death

Somebody to Love: The Life, Death

and Legacy of Freddie Mercury

by Matt Richards & Mark Langthorne

Weldon Owen. 440 pages, $24.95

vFor it was in or around this year, the authors say in their dark opening paragraphs, that scientists—using clinical records and DNA analysis and a bit of guesswork— have pegged the origins of HIV in humans, which ultimately gave rise to the AIDS epidemic of the 1980s, which in turn resulted in the untimely death of Freddie Mercury in 1991.

The coauthors of the 2016 book 83 Minutes: The Doctor, the Damage, and the Shocking Death of Michael Jackson, Matt Richards and Mark Langthorne seem to be carving a niche at the intersection of medicine and celebrity misfortune. In the case of Somebody to Love, the story begins with the initial animal-to-human transmission of HIV (or its ancestor) when an infected monkey is hypothesized to have bitten a Congo warrior, who later slept with a prostitute. Ultimately, in a long, roundabout narrative, this event is linked tenuously to Mercury through his father, a Parsi and follower of Zoroaster who was born in the same year (1908).

Nearly four decades after those concurrent events, at around the time that Farrokh Bulsara (known later as Freddie Mercury) was born, his father had emigrated from India to Zanzibar, where he overcame financial hardships and became well-heeled enough to send his eldest son to private school. Despite a family crisis when he was in his late teens, Mercury was a confident and popular lad who loved the limelight and knew how to put on a show, though he seemed to want to hide his Indian heritage and always referred to himself as Persian because he thought it was more “exotic.” Even so, despite his confidence, he was mostly a hanger-on in his adolescence. He passively waited to be invited to join a band, but once he did, performing with a band called Smile, he “sounded like a very powerful sheep.”

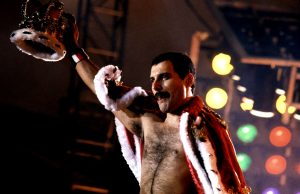

As in most rock bands, members came and went; but once things had sorted themselves out and settled on a name, Queen became the “guinea pig” for an up-and-coming studio that let them record in exchange for a demo tape—their first chance at stardom. It would take a few months before they had their first hit single, “Keep Yourself Alive” (1974), which would be followed by many more written by Mercury, who became obsessed with writing the next hit song. By 1975, he was eager to move on to something more ambitious, a song that incorporated both rock music and classical opera, and the result was “Bohemian Rhapsody,” a six-minute piece in three “movements,” something that had never been done before. Many more albums would follow over the ensuing fifteen years, featuring numerous songs that are now standards by Freddie Mercury, notably “Somebody to Love” (1976, the source of this book’s title), “We Are the Champions” (1977), and “Crazy Little Thing Called Love” (1979).

For all his success, Mercury struggled with his sexual identity both before and during his time as a celebrity. He had his share of friends and girlfriends as a young man, but he seems to have had sexual feelings toward men that he was unable to name or unwilling to own up to. Richards and Langthorne suggest that Mercury may have had sex with men starting in early adulthood, but that later he fell deeply in love with at least two women, regarding one to be on a par with a “common-law wife.” On the other hand, his same-sex feelings lingered on, and Mercury vowed that at some point he would come out publicly as gay. But he never did, at least not officially. While many people had figured out that Mercury was partly gay—his band was called “Queen,” after all—many others were surprised when it was announced, hours before he passed away, that Mercury was dying of AIDS.

Readers should know that this book is as much a history of the AIDS epidemic as it is a biography of Mercury. Indeed, the disease almost becomes a separate character, the villain in a struggle that keeps us on the edge of our seats. As a literary device, this struggle can be overdone, and eventually the dire warnings of the heartache to come start to lose their impact. But between the frequent glimpses into this dark malevolence are Mercury’s life and career, including his gay love affairs, some of which were closer to tricks or casual flings.

Still, the authors can’t resist going back into the HIV drama, and they even get into some detailed speculation into who may have infected Mercury with HIV. In the end they shrug, “That’s anybody’s guess,” though they devote many paragraphs to attempting to link Gaetan Dugas—the alleged “patient zero”—to one of Dugas’ putative lovers, John Murphy, who in turn may have had sex with Freddie Mercury. They even include a hypothetical timeline for the transmissions to have occurred, notwithstanding the author’s frequent use of words like “hedonistic” and “promiscuous” to describe Mercury’s lifestyle.

Among the most compelling pages are those near the end of the book, which recount Mercury’s battle with the illness and the final, sad days and nights. While he admitted being HIV-positive to a small handful of people, and while he appeared to get sicker and sicker, he continued to work, purchased a new home, and signed with a new record label in the U.S. Because of his eagerness to maintain normalcy, few knew for sure that Mercury was dying until he released the news to the press just hours before he died in 1991 at age 45.

Buried beneath a cherry tree in London, his career and early demise put another face on the AIDS crisis and spurred the organization of a benefit concert featuring Roger Daltrey, the late George Michael, Elton John, the late David Bowie, and Annie Lennox, which raised twelve million pounds for AIDS research and awareness. His legacy is intimately bound with that of Queen, which had around two dozen top ten hits in the UK alone. Thirteen years after Mercury’s death, “Bohemian Rhapsody” was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame.

Terri Schlichenmeyer is a freelance writer based in Wisconsin.