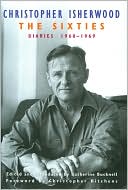

The Sixties Diaries: 1960–1969

by Christopher Isherwood

Edited by Katherine Bucknell

HarperCollins. 756 pages, $39.99

TWO of the three volumes of Christopher Isherwood’s diaries are now out: Diaries: Volume 1, 1939–1960 (1996), with 1,054 pages, and now The Sixties: Diaries: 1960–1969, with 756 pages. There’s one more to come, scheduled for this spring, covering the last dozen years of the novelist’s life.

As someone who has read just about everything Isherwood ever wrote, who’s edited a couple of books about him, and who teaches his novels almost every semester, I’m about as interested in the life and work of this great chronicler of the 20th century as a person could be. And yet, as I read and read and read my way through the 1960’s, I found myself wanting… less. Less about his arthritic thumb, less talk of hangovers, less anxiety about every pain possibly indicating cancer, less worrying about productivity, infidelity, or the weather. I also began to think that some editing would have been a kindness to Isherwood, who is spared nothing in all these pages.

The decision to publish the diaries uncut was made with Volume One more than fifteen years ago, but I’m not convinced it was the right decision. The very capable editor, Katherine Bucknell, certainly has a commanding knowledge of the material and the details; she provides helpful footnotes and a comprehensive glossary of who’s who, but she could have simply announced in her long introduction that she was sparing us twenty percent of the hangovers, complaints, and household chores, and the like.

Instead, we have almost every detail—almost because some names are withheld or disguised, which actually becomes quite an annoying detail. Did Bucknell actually make up these names? Why? Do we need, for example, a pseudonym for Isherwood’s accountant? Or, more tellingly, in a particularly titillating description of some sexual peculiarities of friends, all the names have been made up. So, we have practices attributed to no one in particular. If we don’t have their names, do we care about their anecdotes or their fetishes? I am inclined to say no.

In the midst of all these words and pages, there is, however, much of interest: the author’s observations about his times and places, his interest in how a writer works (or doesn’t), how a relationship persists and grows (and struggles), and how a person ages, fearing his own decrepitude as he watches so many of his friends suffer and die. It is unsettling, in fact, to spend a few hours immersed, say, in 1965, and to come out of the book disoriented about what day of the week it is. Isherwood’s writing is that vivid; his reality is that well conveyed.

In the spring of 1961, for example, Isherwood is in England for an extended stay, visiting his lover Don Bachardy, who’s at art school at Slade in London. The story of this legendary relationship, so well depicted in the 2008 film Chris and Don: A Love Story, is pervasive in the volume, of course. A diary entry for April 28th gives an important insight into Isherwood’s feelings about his native land: “There is much that is lovable here but thank God it is not my home. Never do I cease to give thanks that I left it.” A few weeks later, these thoughts continue: “I realize now, on this trip, that my longing to be away from England has really nothing to do with a mother complex or any other facile psychoanalytic explanation. No, here is something that stifles and confines me. I wish I could define it. Maybe the island is just too damned small. I feel unfree, cramped.” The trip also reveals tension in Isherwood’s longstanding relationships with E. M. Forster, Joe Ackerley, and especially W. H. Auden. Having failed to do much work with Auden and his lover Chester Kallman—they were working half-heartedly on a musical adaptation of Isherwood’s Berlin writings—Isherwood notes on the day of their parting that “there was a feeling of haste and constraint and I don’t think this was at all a satisfactory ending.”

The Berlin musical project brings me to another, quite interesting aspect of the diaries as history. We know how a lot of this turned out, so beholding it in its conception is often fascinating. Even as this musical collaboration with Auden and Kallman founders, we know that Cabaret is coming. We know that the Berlin material contains the makings of one of the most successful musicals (and film adaptations) of all time, and we know that Isherwood will have little (or nothing, really) to do with it. Seeing, also, that Isherwood’s screenplay is rejected, especially after all the work he did on it in the late 1960’s, helps explain why he could never find anything positive to say about the show that made him as rich and famous as he’d ever be.

What is perhaps most curious about The Sixties is that it is almost reticent—even silent—on many major events of that tumultuous decade. Of course, a diary is a personal record, not a history. Nonetheless, history intervenes. So the Cuban Missile Crisis appears in the early years (and in A Single Man), and Isherwood’s close friend Aldous Huxley dies the same day JFK is assassinated. The entry for November 30 opens: “Such a strong disinclination to write anything about Black Friday the 22nd. But I ought to. To remind myself.” Listening to the radio for the accounts of the day, Isherwood writes: “Just disgusted horror … there was the feeling—journalistic as it may sound to say this—that some sort of nationwide evil was functioning. It was something we had all done with our hate. Aldous seemed an anticlimax.” The entry for that day ends, “Life goes on, or stops. If it goes on, it will change for me.”

Two years earlier—another of those historical curiosities—Isherwood and Bachardy were in New York, where they went to the ballet with Lincoln Kirstein, who amused them with a story about a command performance of Macbeth for visiting dignitaries at the Kennedy White House. Isherwood tells it this way: “Lincoln was suddenly told that it wouldn’t be tactful to do Macbeth, because [the guest of honor, an African head of state]had murdered his predecessor in office! Lincoln told them he was sorry, that was the only Shakespeare available; so they did it, and the guest sat there quite unmoved and greatly enjoyed it. There was one crisis, however, when Lincoln found out that the White House security police had confiscated the daggers, because no weapons are allowed in the neighborhood of the president.” One cannot read such a passage, from Christmas of 1961, without shivering a little.

Many hallmarks of the 1960’s are visible throughout the diary. There’s a funny experience of attending Timothy Leary’s “show” at the Santa Monica Civic Auditorium in early 1967: “What was so false and pernicious in Leary’s appeal was its complete irresponsibility. He wasn’t really offering any reliable spiritual help to the young, only inciting them to vaguely rebellious action—and inciting them without really involving himself with them.” The assassination of Martin Luther King gets little notice. The death of Judy Garland and the Stonewall riots go unremarked. The Manson murders get some attention. Here again, knowing how things turned out comes into play. On August 12, 1968, we read that “Sharon Tate, Roman Polanski’s wife, came to see Don about having her portrait drawn by him.” A year later, on August 20, 1969, we get this: “Leslie Caron told me on the phone that the murder of Sharon Tate and the others in Benedict Canyon, followed by the two other murders at Silver Lake and Marina del Rey, created a tremendous panic.”

Having survived a decade of painful growth, separation, and struggle, Isherwood and Bachardy ended the summer of 1969 with a trip to the South Pacific. They flew to Tahiti on “the perfect night to depart—right after the moon rape. (Oh, how sad it was to look up at the poor violated thing and know that it was now littered with American junk and the footprints of the trespassers!).”

The index entry for Don Bachardy is four columns long, so to say that he is on almost every page is just about right. Isherwood records the vicissitudes of long-term relationships. While they had particular challenges—their thirty-year age difference, Isherwood’s fame and success, Bachardy’s artistic development and self-determination—they also clearly loved each other deeply and abidingly. In April 1962, as Don needs more independence, he decides that he wants his own studio space—at their garage. Isherwood slyly records their conversation: “When I ask [why not in Santa Monica], he says jokingly that he wants to keep an eye on me. And I suspect that this isn’t entirely a joke. He is afraid of leaving me too much alone. He doesn’t want my independence.”

A particularly low point in the relationship comes in February 1963: “What I am miserable about is the feeling that Don is gradually slipping away from me. To go to New York with him at this time, especially in order to ‘celebrate’ our anniversary, seems grimly farcical. I don’t feel I have the heart for it. Also, to make matters worse, I have been reading through all these diaries and feel absolutely toxic with their unhappiness.”

Unhappiness is not all. There’s much evidence of work, much attention paid to Isherwood’s spiritual life with Swami Prabhavananda (including a sojourn in India from December of 1963 to February of 1964, which resulted in Isherwood’s final novel, A Meeting By the River), and much chronicling of the days of a long, productive, and fascinating life. Chris and Don dared to make a life together, and it’s all here. Knowing that the relationship with Bachardy survived, even flourished, for more than twenty years beyond those early 1960’s troubles, and knowing that much of Isherwood’s best work was still to come, is a consolation for the reader amid all this sadness, some tedium, the occasional toxic outburst—all of it fascinating in its way, but, still, too much information.

Chris Freeman, who teaches at USC, is the co-editor, with James Berg, of The Isherwood Century: Conversations with Christopher Isherwood.