The Pride

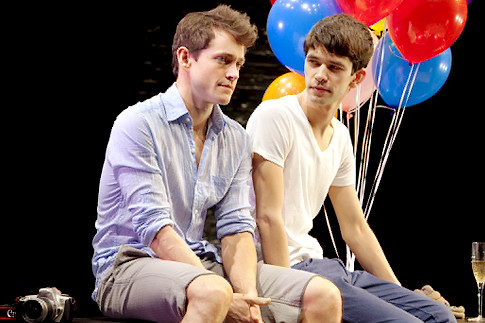

by Alexi Kaye Campbell

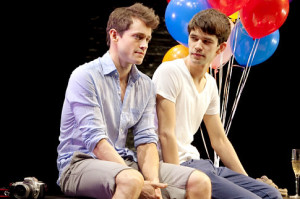

Directed by Joe Mantello

Lucille Lortel Theatre

The Temperamentals

By Jon Marans

Directed by Jonathan Silverstein

New World Stages

PART OF a spate of gay-themed plays on the boards in New York this season, two from Off-Broadway present contrasting approaches to the recent history of same-sex male love. The Temperamentals by Jon Marans dramatizes early activism: the creation in Los Angeles of the Mattachine Society by Communist organizer Harry Hay and his then lover, costume designer Rudi Gernreich, and a small circle of friends. The story unfolds in the early 1950’s with America moving from the war years into the McCarthy Era. The Pride, on the other hand, a first play by Alexi Kaye Campbell, is a British import that views the gay present through the lens of the past. It features two different male couples in London in 1958 and 2008; each pair must come to terms with the personal price of gay relations. In 1958, the context is one of social repression; in 2008, one of sexual and social liberation. In short, The Temperamentals sees the gay past in its political dimensions—The Pride, in its personal and essentially private ones.

Jon Marans, whose play Old Wicked Songs was a 1996 Pulitzer Prize finalist, first presented The Temperamentals in New York in a well-regarded and popular run last year. It returns with its cast intact in a tightly performed production that loses nothing for the modesty of its means. No Broadway pyrotechnics here. Instead, it moves forward on the strength of scenes that quickly establish the growing intimacy between Hay, married and a father, and Gernreich, an Austrian-Jewish refugee of creativity, worldly charm, and personal ambition. Early scenes establish Hay as an inspired idealist who sees his homosexual brethren as a powerless minority without a voice; he is determined to give birth to a political movement on par with the nascent civil rights movement. Hay starts with “Bachelors for [Henry A.] Wallace,” seeing in the progressive presidential candidate a vehicle for advancing the cause of the “bachelor” minority. He soon moves on to a political manifesto requiring signatories. Gernreich is a new love, a witty sparring partner with keener social skills, a world-weary cynicism, and the experience of the Third Reich’s murderous anti-Semitism behind him. Combined, this gives Gernreich a cosmopolitan sophistication and, as played to perfect pitch and Austrian accent by Michael Urie (of Ugly Betty fame), a louche, mordant wit. Gernreich is convinced he can maneuver his Hollywood contacts—he earns a living as a movie costume designer—and he and Hay attempt to enlist “Vincente.” Film director Vincente Minelli, that is, who’s too involved with his movie career and being married to Judy Garland, the most famous female icon of the gay masses, to consider risking the kind of public support Hay and Gernreich seek.

If Marans’ characters are involved in a personal drama that faces outward to a larger world of political activism, The Pride takes its journey into the fraught interior spaces of the heart—and the English drawing room. In 1958 London, successful realtor Philip is married to Sylvia, a former actress turned children’s book illustrator. She has invited a young author and colleague, Oliver, for dinner, on the assumption that her husband Philip and Oliver will get on famously. The conversation between the two men, while Sylvia prepares off-stage for the night out, is one of stiff politesse, forced laughter, and arch comments. While Oliver, a reserved and sensitive type, is quickly perceived to be a gay protagonist, Philip’s smooth if practiced veneer, along with his assertions of devotion to his wife, alert the audience to a marriage that’s in trouble.

But the scene shifts somewhat abruptly to another place and time. A different “Oliver” is abasing himself before a Nazi storm trooper; have we traveled back in time to Weimar Berlin? A scene from Cabaret or Bent? No, the year is 2008, and the contemporary Oliver (no relation to the earlier one) has called in a hustler for a bit of role-playing bondage and submission. Soon enough, this Oliver’s recent ex-boyfriend “Philip” arrives unexpectedly. An emotional row ensues, revealing that the 2008 Oliver is not just sexually liberated but libertine. Anonymous “sexcapades” are the stuff of his free hours and the cause of a recent breakup with Philip, with whom he had enjoyed an otherwise loving relationship.

In The Temperamentals, Thomas Jay Ryan as Harry Hay presents an honorable man at middle age who tries to apply left-wing orthodoxy to a heterodox situation and finds that the rules and strategies have to be made up as he goes along. What the Communist Party has given Hay is the discipline needed to adhere to a just cause. Ryan is at once stalwart and tender in the role, and thoroughly smitten by the more youthful and stylish Gernreich. Michael Urie portrays Rudi as a man with the wit and drive to focus his creative energies on a cause with intellectual heft. Finally, however, the burdens of daring to be “out” as a brave political couple fray the relationship. Career ambition, and perhaps financial security as well, trumps Rudi’s fantasy of storming the barricades. Gernreich will make his name not as a political iconoclast but as a fashion bomb-thrower whose 1960’s topless swimsuit nearly made him a household name. But we learn this only in epilogue, after Hay and the original Mattachine inner circle have been passed over for new leadership, their Communist past having been deemed a detriment to the movement as McCarthyism moved in.

As for The Pride’s two Philips and two Olivers, social mores impact their private lives in two very different periods. The Philip of 1958 takes his wife’s good friend Oliver as his secret lover in a relationship that transpires off-stage. The audience only learns this when young Oliver tries to force married Philip to acknowledge the depth of his feelings—alas, to acknowledge his feelings at all by facing the dishonesty of their game. Marriage has been a mere cover for Philip. The second, contemporary pairing of Philip and Oliver, alive in a world of instant sexual gratification, finds them stumbling to salvage their love from Oliver’s acknowledged and insatiable appetite for anonymous sexual encounters. It begins to seem as if playwright Alexi Kaye Campbell posits monogamous commitment and uncontrollable sexual hedonism as two incompatible poles on the gay spectrum without fully considering how many stages there may be in between.

Meanwhile, middle-class and respectable 1958 Philip is too snugly ensconced as a straight London bourgeois to risk losing it all. The younger Oliver, aware of their joint betrayal of Philip’s wife, is deep in the throes of a love that he believes could last. He excoriates Philip’s dishonesty and weakness. The confrontation scene between them at the end of Act One leads to a shocking act of violence. Philip of 1958 stands revealed as a man at war with his nature, deserving of our opprobrium and our pity. By contrast, the 2008 Philip and Oliver seem at once more like us and less compelling, in part because their dilemma seems so commonplace. Apart from absolute fidelity—hard enough to find in a sophisticated gay or straight couple—the name of the game between gay men is often one of sexual compromise. The preppy-normal Philip of 2008 doesn’t seem to be asking for idolatry from Oliver, only a lover who won’t skip out on him for trysts in dark urban corners every five minutes. Even Oliver understands that his appetites are gluttonous; what he needs is long-term therapy, but this suggestion never arises. This is London, after all, not New York.

If The Temperamentals does not always go deep enough in its exploration of the Hay-Gernreich relationship, neither does it reduce it to mere agitprop. To be sure, the play may have more resonance for those with some background in pre-Stonewall gay history, but its well-written scenes have humor and warmth anchored by two fine central performances. There is also colorful support from three other actors who, in multiple roles, sketch the contours of a gay community living as social lepers. In this recounting of our past, we’re at our best when we are fully aware of our social and political predicament and fight back against circumstances. But the play’s postscript acknowledges that this does not necessarily bring about instant change or secure personal happiness. It can, if only briefly, bring into focus what the ultimate goal might look like on a distant horizon, and how far the journey might be.

In The Pride, by contrast, individuals negotiate not with their society, but with each other; it is up to us to discover and live out the truth of our natures, and some of us haven’t the strength to surmount the social limits. The Philip of 1958 seems incapable of moving beyond his need for normality as it was defined then, but perhaps no less than the Oliver of 2008 knows how to avoid the siren call of the hedonism so widely available to him. That playwright Campbell may present a false choice is never acknowledged in the play—though that might mean we would need to consider that not every gay relationship has to be “exclusive” for all time. Alas, The Pride poses interesting questions but has a far more satisfying dramatic and emotional arc in Act One than it manages in Act Two. In fact, these are not questions peculiar to gay relationships, but because of longstanding traditions of courtship and marriage, it only seems as if heterosexuals don’t face the same predicaments. But with every fresh scandal—from Eliot Spitzer to Tiger Woods—we rediscover what horn-dogs men can be.

What ever happened to pre- and post-World War I bohemian ideals of “free love” that seemed to transcend the identity categories to which we cling today? We may have to go further back in our collective social history to glimpse a fresh set of utopian templates that were at once private solutions and revolutionary ideas.

Allen Ellenzweig is the author of The Homoerotic Photograph (1992) and a frequent contributor to this journal.