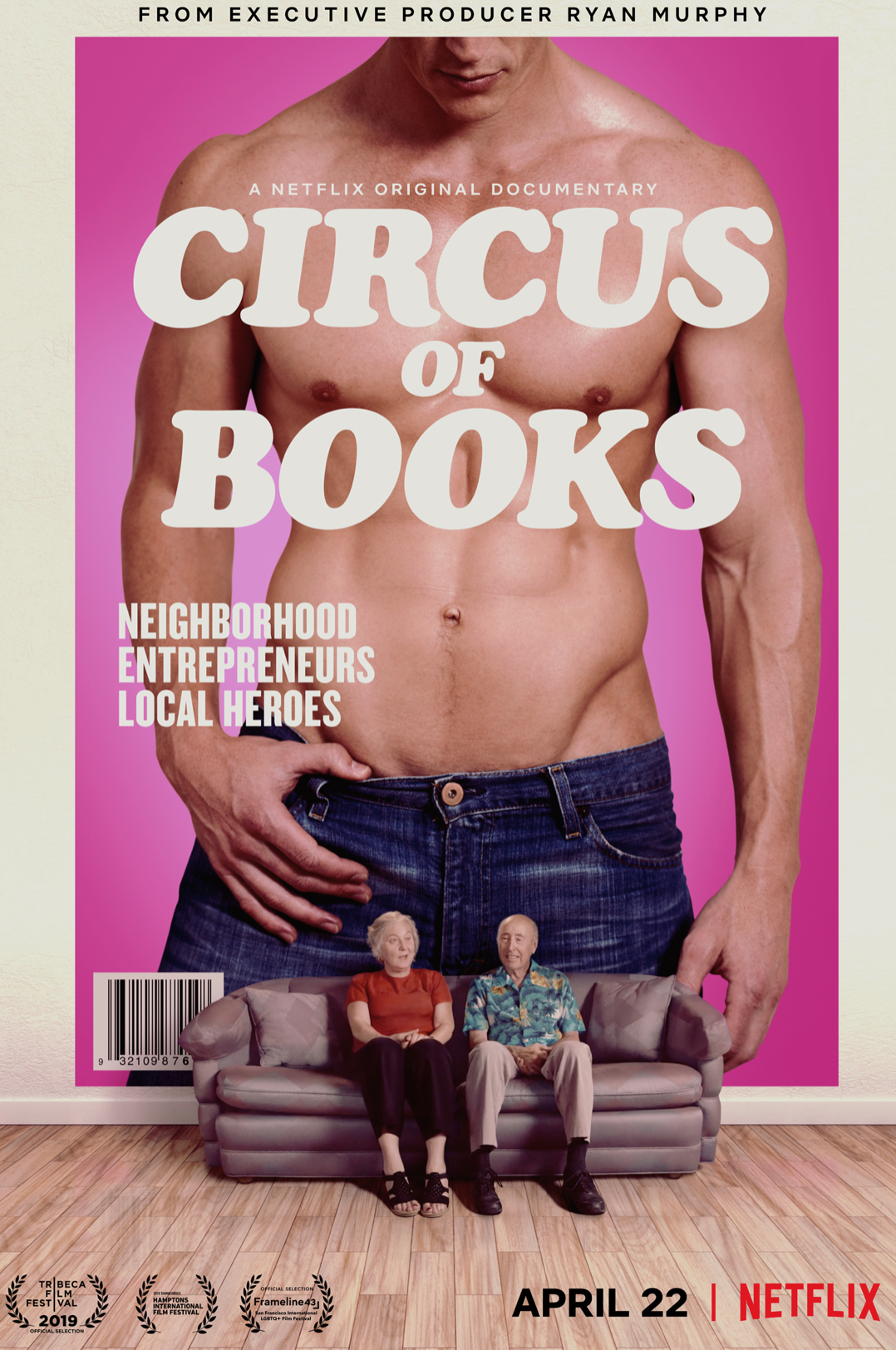

CIRCUS OF BOOKS

CIRCUS OF BOOKS

Directed by Rachel Mason

Netflix

HOLLYWOOD

HOLLYWOOD

Directed by Ryan Murphy

Netflix

“EVERYBODY comes to Hollywood [and]wants to make it in the neighborhood,” Madonna mused nearly two decades ago, asking: “How can it hurt you when it looks so good?” That paradox—all the glamour and grime of show business—is well depicted in Circus of Books and Hollywood, a documentary and miniseries, respectively. The two share an interest in the margins around Tinseltown, especially its LGBT subculture and what “hustling” means in various forms. They are also the first fruits of that jaw-dropping $300 million contract that writer-director Ryan Murphy scored last year. Having given audiences Glee, The Assassination of Gianni Versace: American Crime Story, and the film adaptation of the late Larry Kramer’s The Normal Heart, the 54-year-old director and renowned workaholic continues to cultivate some of the queerest content on TV.

Although Karen had cut her teeth as a distributor for Larry Flynt, the Masons are the mirror opposites of Flynt or Hugh Hefner, porn’s defiant founding fathers. Karen is devoutly Jewish and cares only about the profits, not the porn. Forced to explain the family business, she glances at Barry before blurting it out: “Circus of Books is a bookstore and a hardcore gay adult business.” There’s a fascinating faux naiveté at work, especially when it comes to Karen, who rushes through an adult novelties expo like she’s doing last-minute Christmas shopping. “I don’t particularly enjoy looking at it,” she tells a dildo salesman, “I can notice it without looking at it.”

Titles such as Meat Me at the Fair and Hard Ball elicit guffaws from the film’s commentators, including none other than Jeff Stryker. When the star isn’t marveling at the action figure made in his image—“anatomically correct, so this is where I have an edge on Ken,” he boasts—he describes the Masons’ mind for business, saying: “You’d never expect these people to be distributing adult movies worldwide but they looked at it the same way I looked at it … supply and demand.” But the Mason family’s kinship with gay culture was not solely based on serving its own self-interest. Pornography, love it or hate it, played a vital role in the gay rights movement by granting visibility to people and pleasures otherwise suppressed. As one loyal customer puts it: “To see men naked … that gave us a lot of pride.”

Given her emotional connection to the material, Rachel Mason’s one-of-a-kind home video is a moving portrait of her parents’ work ethic and empathy. Visiting several of their employees as they lay dying of AIDS, they acted as the surrogate parents to men whose actual parents had shunned them. Behind the shop was a vibrant spot known by locals as Vaseline Alley, where one customer claims to have lost his virginity to a cop in training. It was, he tells the camera excitedly, “every queer boy’s wet dream!” Circus of Books is also the story about a gay neighborhood. Running parallel with the Mason family circus is the coming-out story of their son Josh, a process that his gay-porn-dealing mother has a surprisingly hard time accepting.

Naked men inspire more than just pride in the splashy, seven-part series Hollywood, which imagines an alternative reality where a big movie studio in postwar America not only casts but champions actors of every race and sexual identity. “Could one movie change the way a nation sees itself?” asks one announcer in a movie-trailer. Hollywood thinks it can. Jack Picking plays the real-life legend Rock Hudson who, in the 1940s, was a Navy veteran named Roy Scherer and just off a Greyhound bus from Illinois. He falls head-over-heels for Archie (Jeremy Pope), an African-American screenwriter who has written a script titled Peg (renamed Meg) that will eventually feature a black actress in the starring role. A cadre of forward-thinking directors and editors put their careers on the line to see that Laura Harrier (as Camille) is cast in that role. Behind the scenes as well is Ernie, a failed actor who runs a gas station that hires the best-looking attendants in town. When not pumping gas, they’re servicing Ernie’s customers—many famous actors and actresses—in a trailer parked behind the gas station. Ernie, who’s based on the real-life figure Scotty Bowers, knows a pretty face when he sees one, so he scoops up Archie, Rock, and Jack as escorts and teaches them how to hustle.

For Ryan Murphy, the show cannot go on without the grande dames of film and stage. Never mind his soft spot for actors whose seductive good looks border on the supernatural. Without his usual muse, Jessica Lange, he turns to Holland Taylor and Patti Lupone, the latter in the role of Avis Amberg, the wife of a Selznick-like studio head, who channels her inner Mae West, mink stole and all. Another Murphy regular is Jim Parsons, who recently led the ensemble cast in the Broadway revival of The Boys in the Band. As Henry Wilson, he reprises the “bitter old queen” type. Wilson is a closeted talent manager who sexually harasses the wide-eyed Hudson in ways that prefigure the casting couch of Harvey Weinstein. Queen Latifah makes a cameo as Hattie McDaniel, the first African-American Oscar winner (for Gone with the Wind), who urges Camille not to accept segregated seating, as she had, at the awards ceremony.

Hollywood takes the happily-ever-after ending to the extreme—spoiler alert!—by sending Rock and Archie, as an interracial same-sex couple, down the red carpet on Oscar night. Critics of Hollywood claim that such distortions are dangerous and that 2020 is simply not the year to wave away racial strife with a magic wand. It’s one thing to imagine the future, they argue, but another to re-imagine a nation’s painful past. But Hollywood doesn’t aspire to be anything more than counterfactual froth and fantasy, perfectly timed for life in isolation when “Dreamland” is what many of us need. Sure, Arnie’s speech in the final episode (titled “Hollywood Ending”), in which he announces that “I’m showing up at the Oscars with [Rock Hudson] on my arm … telling the world that we refuse to hide,” is a little hokey. But there’s another word for it, and that’s “entertainment.”

Colin Carman is an assistant professor of English at Colorado Mesa University. He is currently writing his second book with a focus on happiness in the novels of Jane Austen.

Discussion1 Comment

I really enjoyed watching Hollywood. It had style, interesting story lines, excellent acting, brilliant sets, and an insight into the Hollywood “dream” (for which read “nightmare”) factory. In fact, the film is all about whether Hollywood is a dream or a nightmare for the people involved.

This was its strength and weakness. Hollywood was never much good at challenging discrimination, and promoting difference. Producing drama like this that pretends that it did, is frankly, nonsensical. Hollywood was discriminatory, and should be remembered as such. The plethora of minorities ultimately triumphing against all the odds, was nothing short of revisionism. There is an issue about portraying truth underlying the modern – “let’s see things how we would like to see them rather than how they actually were” – leading to false understanding, misrepresentations, and an extremely skewed version of history, that pervades much modern drama.

Picking up fragments from the past, using the names of real actors in scenes which seem to be based on very flimsy evidence or did not happen, is not in my view the best way of understanding or presenting history. Or, for that matter, fair on the real people (but now dead) named in the drama.

Fact and fiction are two distinct and not overlapping categories. To conflate them together does nothing to advance the cause of equality and acceptance.

I have always fought for equality for all, and as a gay man, understand discrimination and how it works. But to revise the highly discriminatory history of Hollywood, for the sake of producing uplifting drama, I found rather distasteful. Yes, I’m sure that there were people in Hollywood working toward the end of discrimination. The historical evidence was that it never became a mainstream movement, more of a step change reflecting social norms rather than producing a new world-view. That was done outside of the dream/nightmare factory. To appropriate the end of discrimination with the actions of Hollywood is an historical travesty.