Editor’s Note: Memorial programs were held in both Boston and New York City this past fall to celebrate the life of activist Urvashi Vaid (1958–2022), who passed away last May. Her longtime friend and “co-conspirator” Richard Burns delivered the first of many eulogies at both programs. What follows is based on the Boston speech, which was delivered on September 28th at Northeastern University. A few items have been included from Richard’s remarks in New York (November 3rd), which began with the following prefatory statement:

You can see in your program that there’s a campaign to put Urvashi on a United States postage stamp. Stamps are planned three years in advance, and the time is long overdue for us to have an activist lesbian leader on our mail. You’ll be shocked to know that this will be a very political process, and the people in this room could make it happen.

The New York program was streamed live by the American LGBTQ+ Museum and can still be viewed on their website (americanlgbtqmuseum.org).

URVASHI VAID and I met in Boston 42 years ago on our first day of law school at Northeastern University in 1980. She was in the student lounge reading a copy of Gay Community News, where I had been the managing editor until the day before. I approached her, and she said: “Haven’t I seen you around at some demonstrations?”

We quickly became friends and co-conspirators at the Law School and at GCN, the national queer liberation newsweekly where so many of us figured ourselves out as young organizers. Urv believed in radical change and in breaking some dishes, but she also believed in the necessity of building social infrastructure and in working in community and in institutions. She created, led, and participated in so many organizations and projects and boards, and I want to bear witness to the vastness of her work and passions with just a small sample of some of the places where she made a difference.

During her years in Boston, she not only went to the Pride march, she immediately joined the Pride March Committee. While we were in law school, she joined the board of GLAD, the Gay and Lesbian Advocates and Defenders, a legal organization that John Ward founded to fight police harassment and entrapment of gay men in parks and restrooms, and that went on to win the fight for the right to marry in Massachusetts.

In 1982, Eric Rofes, also part of the GCN crowd, led the founding of the Boston Lesbian and Gay Political Alliance, BL/GPA, or, as Charley Shively used to call it, Bilgepump. So Urv joined that board and became a firebrand at BL/GPA as well.

In law school, some of our professors said to us that they had never actually talked to an openly gay person. So Urvashi and Kevin Cathcart and I made appointments with every member of the Law School faculty to fill them in our existence and to urge them to include lesbian and gay issues in our legal studies.

After graduation in 1983, as a young lawyer Urvashi joined the National Prison Project at the ACLU in Washington, DC, and later joined the staff of the National Gay & Lesbian Task Force, first as the director of communications in 1986, right before Sue Hyde joined the staff.

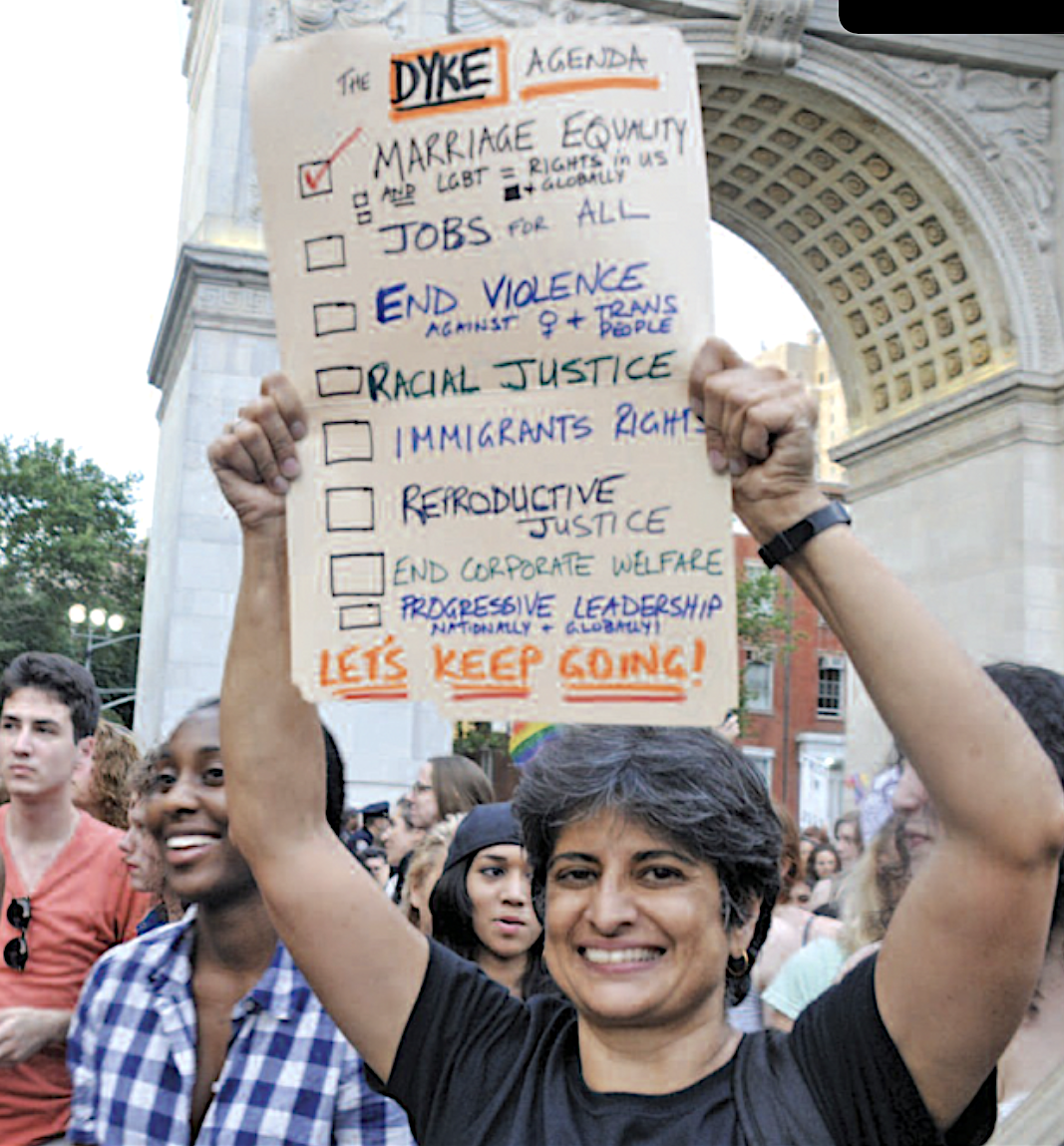

Later, Urv became the executive director of the Task Force. And that was a big change—for the Task Force. She positioned the group to reflect her vision of a larger movement, one that would push the rest of our movement to act with the integrity that her vision and principles required, a movement that would work at the intersections of race and gender and money and queerness. And it was not easy. You can imagine the constant pressure she placed on the Task Force’s sister organization, the Human Rights Campaign Fund.

At the Task Force, she and Sue Hyde cofounded Creating Change, the annual conference that has trained literally tens of thousands of young activists. And there she also conceived of the National Religious Roundtable and the Equality Federation.

And then she came to New York. Something not too many people realize is that she had a major impact on philanthropy and its approach to LGBT people and causes. She played key roles at three of the largest funders of LGBT equality in the world. First, at the Ford Foundation she rose quite quickly in leadership and for five years advocated not only for lgbtq equality but for increased funding in the rural South; and loudly, perhaps inconveniently, she argued to defund Harvard University.

She then went on to be the executive director of the Arcus Foundation for another five years and successfully integrated racial justice into their LGBT DNA, a commitment that they continue to this day. Arcus, which is a private foundation, is the largest funder of queer equality in the world. She spent ten years on the board of directors of the Gill Foundation, another one of the largest funders of LGBT equality, and there she learned she could be the only woman in the room, she could make a lot of noise, make change, and at the same time make lifelong friends. And then, when she retired after ten years from that board, they brought in Mary Bonauto to succeed her.

Urv went on to serve on the National Board of Directors of the ACLU, she cofounded LPAC, the first Lesbian Political Action Committee, and she founded the Donors of Color Network, the first ever cross-racial community of donors of color. She cofounded the national lgbtqa Anti-Poverty Action Network and the National LGBT HIV Criminal Justice Network. And in her spare time, she co-created the Provincetown Commons, the collaborative space for artists in P’town. She was chair of the National Planned Parenthood Fund board of directors. For the last five years of her life, she was a cofounder of the American lgbtq+ Museum for History and Culture in New York City.

And on and on; it’s exhausting just to recite them all. And this is a fraction, the edited version, of where she had an impact as a leader in the infrastructure to create change in this country and in the world. And so, my personal plan is that Urv will end up on a U.S. postage stamp. And all of you can help. There’s a letter-writing campaign going on right now led by the woman who fought successfully to have Harvey Milk placed on a stamp.

I’ve watched some of Urv’s early speeches from thirty years ago, and, as has been widely reported, she was ahead of her time in beseeching and demanding and leading our movement for equality into a broader movement for freedom and justice and dignity for everyone. She wanted to make us all understand the direct connection between our LGBT equality and reproductive freedom and gender and racial justice. Recently a friend pointed me to a transcript of a conversation Urvashi had with Larry Kramer in 1994 while she was writing her first book, Virtual Equality. Here’s the rough quotation:

Creating this common movement, for lack of a better word, the way I’m trying to approach it is: what if we shifted the framework? What if instead of saying, I’m in coalition with you, we tried to identify how HIV treatment issues connect with racism? It’s going to express itself differently in your life than in mine. And that’s the case in reproductive choice. It was never the case that men should march with women because they support women; it was that men should march for reproductive freedom because we’re marching against the power of the state to tell you and me what we can do sexually, period. And that’s the issue. That’s the common thread, right? If the state can say that I can’t have an abortion, the state can say that you can’t have sodomy.

Larry Kramer replied: “I have to tell you, I never realized that.” Urv laughed and said: “It’s about state power. I mean, that’s why I say maybe if we were all to think, to try and explain the connections, I think you’d see things in a different, more connected way.” So here is Urvashi defining intersectionality 28 years ago. Today, after the fall of Roe v. Wade, these connections are all too obvious to everyone.

Urvashi’s impact as a writer and thinker was tremendous. She reached so many people with speeches at forums and marches like the National March on Washington in 1993. While writing her first book, Virtual Equality, she went on the college circuit in order to support herself. This is how she made her living. She reached literally tens of thousands of rising leaders through these talks. She inspired and ignited many young queer activists.

That’s the public impact that Urvashi had. But for me, I can barely speak about the loss of my friend of 42 years. Urv was generous, she was tough, she was kind, and she was incredibly bossy, but she really hated it when I was bossy. She could be quick to anger and quick to forgive. Her ability to challenge us all was so imbued with compassion and love and charm that we could take it. She was relentless. She was endlessly supportive of her friends, she liked to dance, and she liked to talk about sex.

While we were in law school, if I told her about a new sex club, she wanted to go too. And so then we did. There was one particular club that was behind the old police headquarters on Berkeley Street in Boston. It was in the back of the building and up some stairs. We would go there and then we’d get thrown out when they figured out that she wasn’t a guy.

She liked to drink and do drugs, until she didn’t. She told me that she would always save a folding chair for me with my name on it in the circle of the church basement. She liked to cook Indian food and to feed everyone and to send you home with leftovers. She was the person who taught me to say “I love you” without the whole world crashing down. She always challenged us and gave us lots to think about. She was a lot.

Urvashi’s deepest happiness was rooted in her decades-long love affair with Kate Clinton. That gave her so much joy.

I know that I think about her every day, and I know that all of us will keep on fighting with the integrity and the anger and the joy and laughter and love that Urvashi did. So, thank you.

Richard Burns is board chair of the LGBTQ+ Museum and is interim executive director of the Johnson Family Foundation. He has held executive positions at many nonprofits, including Lambda Legal, the Drug Policy Alliance, Funders for lgbtq Issues, and the Arcus Foundation.