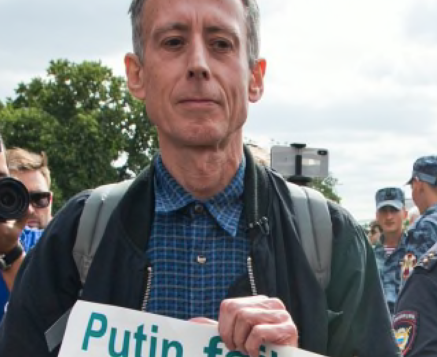

SIMPLY STATED, Peter Tatchell is the doyen of the LGBT rights movement in the UK. Since his arrival in England (from Australia) in 1971, he has been instrumental in founding and energizing a number of key organizations, including Britain’s Gay Liberation Front and OutRage! His commitment to LGBT and broader human rights causes has involved him in over 3,000 nonviolent direct action protests, including many that have put his personal safety at risk, such as his protests in Moscow against the crackdown on LGBT rights in Russia and his two attempts to conduct a citizen’s arrest of Robert Mugabe.

I first became aware of Tatchell’s work when, as a closeted eighteen-year-old, I followed his campaign to be elected to Parliament as a member of the Labour Party. His opponents’ leveled homophobic attacks upon him as an out gay candidate made the national press and helped to cement his status as an icon of the LGBT movement—a perennial thorn in the side of those who opposed equal rights for all.

I was fortunate enough to meet Peter Tatchell on several occasions when we shared the platform at various LGBT events in the UK over a decade ago. He would be there to deliver the keynote speech, and I would be there with my band to sing a few disco hits at the end of the rally. He was always incredibly kind, interested, and gracious toward us.

This interview was conducted via Zoom late last year.

David Wickenden: If you don’t mind, I’d like to go back to when you first arrived in the UK, which I believe was 1971, a couple of years after the Wolfenden Report, legalization of homosexuality in the UK, and a couple of years after Stonewall. What was it like to be a gay man in the UK at that time?

Peter Tatchell: Can I just make it absolutely clear that it was a partial decriminalization of male homosexuality in 1967, and in fact the number of arrests of consenting adults for same-sex behavior increased by 400 percent in the few years after 1967. Full decriminalization didn’t happen in England and Wales until 2003, not in Northern Ireland until 2009, and not in Scotland until 2013.

DW: Thank you for clearing that up. Well, what was it like to be a gay man in those days in the UK?

PT: Well, most aspects of gay male life were still criminalized, despite the partial decriminalization of 1967. So sex was only lawful if it took place between two consenting adults civilians, aged 21 or over, in the privacy of their own home with doors and windows locked and closed and with no other person present in any part of the house. There were no public figures who were openly LGBT. The only time LGBT+ people were ever mentioned was when they were exposed as spies, child sex abusers, or mass murderers. You know the medical and psychiatric professions still designated homosexuality as an illness and supported various cures, including electric shock aversion therapy, funded by the National Health Service.

DW: What were your priorities then at that time as an activist?

PT: Well, I was very quickly involved in the newly formed Gay Liberation Front in London. Our agenda was really to take on the establishment over its homophobia, biphobia, and transphobia, so this included campaigns for an equal age of consent.

We also had campaigns against the medical and psychiatric professions and did zaps of Harley Street [London’s medical district] against well-known psychoanalysts and psychiatrists who were advocating the curing of homosexuality. I staged a protest at Saint Thomas’s Hospital in London during a lecture by Professor Hans Eysenck, who was then one of the world’s most famous psychologists. He was justifying the use of electric shock therapy. I was dragged out of the meeting and beaten up by doctors and medical students.

The Gay Liberation Front also did big protests against Festival of Light, which was a Christian-led morality campaign targeting abortion, pornography, and homosexuality. The leading lights of that campaign were very hostile to LGBT rights, so among other things, we invaded their launch meeting at Westminster Central Hall and disrupted it with nuns in drag. We released mice into the audience, and others of us stood up and held a same-sex kiss-in.

DW: So many of your forms of protests demonstrated incredible courage and bravery but also theatrics as well, which I think is a particular kind of phenomenon in the LGBT community. What impact would you say that Stonewall had on the gay community in Britain?

PT: Well, I think people heard about the Stonewall riots and subsequent gay liberation protests in New York and other cities, and that was partly the inspiration for the formation of the Gay Liberation Front in the UK. In fact, two young students, Bob Mellors and Aubrey Walter, went to the U.S. in the summer of 1970 or ’71 and joined a GLF protest in New York. They also attended the Black Panthers Revolutionary People’s Convention in Philadelphia, where Huey Newton welcomed LGBT people into the liberation struggle. So, they returned to Britain inspired by these experiences, and they were the ones who called the first meeting of what was to become the GLF in London at the London School of Economics in October 1970.

DW: I guess the whole pride movement sprang out of that as well in subsequent years.

PT: Right. The GLF took the initiative in organizing Britain’s first-ever Pride parade, which took place in London on the 1st of July 1972. I was one of about thirty people involved in organizing and publicizing the Pride event. We had no idea what to expect, because in those days most LGBT+ people were closeted. They wouldn’t dare show their faces, so we were very pleasantly surprised when about 700 to 1,000 people turned out. We rallied in Trafalgar Square and then marched to Hyde Park, where we had a gay day. I’ve got to say that the police presence was extraordinarily heavy. There was almost one police officer for every marcher and some of the officers hemmed us in, shoved us, and openly abused us.

DW: What was the response from people in the streets?

PT: About a third of the public was clearly hostile. They shouted abuse, and some even threw cans and coins. About a third was just sort of disbelieving and gaping. They couldn’t believe that gay people would dare show their faces. The other third was actually quite supportive, so we had cheers and applause as well. It wasn’t all negative. That gave us great hope and gave us the confidence to keep fighting.

DW: And what would you say would be the legacy of Stonewall for the gay community in the UK?

PT: I think Stonewall’s legacy is actually quite limited. It was something that happened in the U.S. We acknowledged it, we appreciated it, but we were determined to chart our own course based upon our own circumstances, history and traditions.

DW: I’m going to move forward the 1980s, which of course were dominated by the AIDS crisis. How did that emerge for you as someone who lived through it?

PT: The first we heard was in late 1981, early 1982, that gay men were dying of some new mysterious disease, and there was very little knowledge or awareness. We very much looked to the U.S., where these cases had been reported, for a lead. So, the gay press here—Capital Gay, Gay Times, Him magazine—really took the lead in publicizing what information was available. When the first person died of HIV in Britain in 1982, that led to the formation of the Terrence Higgins Trust, which is still the main HIV charity in Britain.

We were very conscious of the need to inform and educate our community. Initially the advice was: Don’t have sex with Americans. I and others knew that was not an adequate response. Almost certainly the virus was present in Britain by the time we became aware of it, so we had to think about what other measures could be taken to protect oneself. So the obvious thing was to use condoms, but there was quite a lot of resistance within the gay male community to condom use. Many people regarded them as a spoiler. But eventually, as sexual transmission became verified by medical research, condom use became the norm.

We also had the government of Margaret Thatcher, which was indifferent to AIDS, and we had a vast public hysteria and panic, which resulted in AIDS being dubbed the “Gay Plague.” There was a huge escalation in threats, abuse, and violence against LGBT+ people.

DW: You mentioned the indifference by the Thatcher administration. Can you talk a little bit more about that? Was is it indifference, or were they more overtly opposed to taking action?

PT: Until the first heterosexual person died of AIDS, the government basically did nothing. As long as just gay and bisexual men were dying, they looked the other way, so the Terrence Higgins Trust really struggled to get even meager funding. I think eventually it got something like £35,000, which was a drop in the ocean. So we felt that this was clearly a government that was not recognizing a looming medical emergency and that was allowing its judgment to be clouded by homophobia.

This was a time, of course, when the Thatcher government had two consecutive campaigns. The first was for a return to Victorian values and the second was for family values. And in both those campaigns there was no recognition of LGBT+ people. On top of that, we did have in the late 80s Section 28, the first new anti-gay law in Britain for a century, which prohibited the so-called promotion of homosexuality or same-sex relationships. This led to a huge mass of censorship, mostly by local councils and education authorities, but also by some local health authorities. It led to gay-themed plays being withdrawn from schools, gay-themed books being taken off library shelves. It led to violent attacks upon theaters that were independent and were performing gay-themed plays. It was a very hostile and quite violent time. The number of gay and bisexual men arrested for consenting adult same-sex behavior skyrocketed.

Simultaneously, the number of gay and bisexual men who were being murdered escalated dramatically. Between 1986 and 1991, I identified 51 murders of men where the circumstances pointed to a homophobic motive, and that’s just the cases that were drawn to my attention. I’m sure the real figure was even higher. It was on a level with race attacks and race murders, but it was almost unreported, and the police were the perpetrators, not the protectors.

DW: Do you think that in some respects this backlash served to galvanize the LGBT community?

PT: Well, the formation of Stonewall, the parliamentary lobby group, and OutRage!, the direct action protest group, were direct consequences of this escalating homophobic atmosphere—escalating police arrests of gay and bisexual men and the failure to investigate the murders of gay men.

PT: We very much issued an ultimatum to the police. We want protection, not persecution. And we mounted a series of high-profile public protests against police harassment, including the use of agents provocateurs. These were young, attractive officers who dressed up in a gay style, then went into a public toilet, park, or cruising area and gave gay men the come-on, and any man who then responded would be arrested. This is clearly police entrapment. So we did a number of things, including picketing police stations, invading police stations, and interrupting police press conferences. We also photographed police agents provocateurs and put their pictures on toilet doors and toilet cubicle doors or strapped them on trees in cruising areas. We were all about exposing what we said was a misuse of police resources and public money.

DW: And could you feel public opinion swinging the way of the gay community through this process?

PT: It did. OutRage! had a very sophisticated campaign. We really professionalized protest, producing slick news releases that were very authoritative, quoting exact laws, giving examples of individuals who were victims, and offering them to the media to be interviewed. Journalists really praised us at the time, saying that we were incredibly efficient, effective, and professional, and that gave them the confidence to take our news releases and report them, because they knew that we could be relied upon in terms of accuracy and honesty. So, we got masses of coverage in the press and on radio and TV. I and other OutRage! spokespeople would be on TV news programs, discussion programs, radio talk shows, etc., day after day. Through this process we were able to change hearts and minds. It wasn’t an accident. Our strategy was to do imaginative, exciting, daring, provocative protests that would get media coverage. And through that media coverage we would raise public awareness about the scale of anti-LGBT discrimination and violence.

DW: You mentioned some of the more spectacular stunts that you pulled with OutRage! Can you talk about a few of them?

PT: Well, some of the spectacular OutRage! protests included the kiss-in in Piccadilly Circus in the early 1990s, which was to challenge the way that the police were arresting and securing the conviction of same-sex couples for simply kissing or holding hands in public. So, for example, there’s a famous case of two lesbians at a railway station who were arrested for giving each other a goodnight kiss as one got on the train. We decided to defy the law and we issued a challenge: We’re holding this mass kiss-in. Come to Piccadilly Circus and arrest us all if you believe this law is worth defending. There was already public outrage over this, because even people who didn’t agree with homosexuality thought this was pretty excessive. So, come the night of the kiss-in, an hour beforehand, the police announced that henceforth in London they would not arrest any same-sex couple for merely expressing affection in public. We won before the kiss-in even began, so it turned into a huge celebration instead.

Another example was a “Turn In” that we organized at Bow Street Police Station, where Oscar Wilde was taken when he was arrested in 1895. We signed statements and then turned ourselves in to the police at Bow, saying that we had sex before the lawful age of consent of 21, or that we had sex with more than two people. Statements were taken, but no one was ever prosecuted.

Another example was the naming of the ten Anglican bishops in 1994, where we called on them to tell the truth. They weren’t being targeted because they were in the closet. It was because they were colluding with a church that was seriously homophobic. The Church of England not only said that homosexuality was sinful but also that the law should discriminate against LGBT people because we were “inferior.” So we named these ten Anglican bishops on the steps of the General Synod of the Church of England, which is their Parliament, and called on them to tell the truth. They were saying you should always tell the truth, but they weren’t telling the truth about their own sexuality. As far as I know, none of those bishops ever again said anything anti-gay. Some of them actually eventually came out in support of our community. The church was so embarrassed that it organized for a senior Bishop to begin the first-ever liaison with the LGBT community. Soon thereafter, the House of Bishops issued a strong declaration against homophobic discrimination.

And then there was the protest in Canterbury Cathedral on Easter Sunday in 1998. Seven of us OutRage! members walked to the pulpit to condemn the Archbishop for saying that gay people were inferior and that the law should discriminate against us. He was lobbying Parliament to oppose equal-age consent, to oppose legal recognition of same-sex relationships, to support the idea that employers should in certain circumstances be allowed to discriminate against LGBT+ staff and so on and so on. We did not interrupt the sacred parts of the service. We waited until he began his sermon and then went into the pulpit peacefully. I, as a lead person, publicly criticized the Archbishop, saying that discrimination was not a Christian value. We were arrested. I was eventually charged under the Ecclesiastical Courts Jurisdiction Act of 1860, which says that any interruption of a minister of religion in a church is “indecent behavior,” and I was duly convicted. I could have been fined £5,000 and sent to prison for six months. The magistrate decided the punishment should be a fine of £18.60, a reference to the 1860 Act under which I’d been convicted.

DW: That was one kind of direct action, but earlier you ran for a seat in Parliament in Bermondsey in 1983 after serving as a replacement MP starting in 1981. How do you see the balance between direct action and mainstream political action on the other?

PT: I always take the example of the suffragists and the suffragettes in the battle for women’s right to vote. The suffragists worked within the parliamentary system and played by the rules, but they didn’t make much progress. The suffragettes did the direct action to shake up the establishment and to put the struggle in the news, and that’s the way I’ve seen the LGBT+ struggle as well. I was not against the Stonewall group and their parliamentary lobbying, but largely they didn’t get anywhere. It was only when OutRage! came along and began to shake things up that things began to change. It was a bit like good cop, bad cop. OutRage! created the discontent that led the people in power to think: we’ve got to do something about this. But rather than deal with the scary OutRage! people, they went to Stonewall, which pushed the agenda forward in more orthodox and discreet ways. But I think you need both.

The other thing I would say is that Stonewall had a more limited agenda, focused purely on equal rights within the status quo, whereas OutRage!, like the GLF earlier, was much more critical of the social order. We had a much more skeptical view toward the laws, institutions, and values of mainstream society. We didn’t want LGBT equality within an unjust system. So, for example, on the issue of sex education in schools, Stonewall was all about just getting LGBT issues included within the curriculum. OutRage! was saying, look, the curriculum is rubbish when it comes to sex in general. We want better sex education for all kids, whatever their sexuality, whatever their gender identity.

DW: Can I just take you back, briefly, to when you were running for Parliament? I remember vividly the kind of homophobic attacks that were thrown at you, mainly by the Liberals. How did it feel at the time to be facing that level of attack from the political system?

PT: Of course, I was running as a left-wing Labour candidate who supported LGBT+ rights, and I think that my manifesto for LGBT+ rights is more radical than anybody else has advocated before or since. It was a very detailed manifesto. No disrespect to others who went before or came later, but it was very far-reaching, though very much within the mainstream of liberal human rights values.

I think Gay News described what happened to me as the most sustained vilification of a gay person since Oscar Wilde. Lots of media commentators and journalists describe the Bermondsey by-election as the dirtiest, most violent, and definitely the most homophobic election in Britain since the Second World War. I was subjected to almost nonstop smears, attacks, and vilification by the tabloid press. There were about fifty attacks upon my flat, including the bricks and bottles through the window—even a bullet through the front door and an arson attempt. I was also physically assaulted over 150 times while out canvassing on the doorsteps, so it was very tough and very frightening. But I was determined. I felt I was fighting a just cause. And what’s interesting is that all the positions that I was denounced for as extremist are now the mainstream. I argued in favor of a comprehensive act to protect everyone against discrimination. It was denounced as extremist, but it has been part of British legal fabric since 2010.

DW: What do you see as the as the remaining challenges for the LGBT community?

PT: Well, there are a number. First, we do need to secure reform of the Gender Recognition Act to allow trans people to self-identify through a statutory declaration. It exists in quite a number of other countries successfully without a problem. You know, it’s quite wrong that trans people have to go through so many hoops now to get a legal recognition of their status.

We need to outlaw conversion therapy. This was promised by the Conservative government in July 2018, and it still hasn’t happened. The prohibition exists already in many other countries and states in the U.S. and Australia.

We’re pressing for compensation for gay and bisexual men who were convicted and either fined or imprisoned under historic anti-gay laws. Many of them suffered terribly, not only imprisonment but also beatings and abuse, and threats and menaces within prison, sometimes by other inmates and sometimes by prison staff. Those who weren’t in prison were often whacked with huge fines that caused them financial hardship, and many of these men eventually lost their jobs, their homes, their marriages. Many ended up anxious, depressed, and even suicidal. So we think it’s right that these men should be compensated for the suffering they endured. But again, the Conservative government has stonewalled.

We also need to end the way in which the Home Office treats LGBT+ refugees fleeing persecution in countries abroad. At the moment, they’re liable to be held in asylum detention centers, which are essentially a prison by another name. Either that, or they’re banned from working and forced to live in substandard Home Office hostels, often sharing accommodations with homophobic refugees who abuse them. They have to live on a meager state stipend of less than £40 a week for food, clothing, travel, phones, etc. It’s impossible, and it’s causing great hardship.

Finally, the government needs to act on mandatory LGBT-inclusive relationships and sex education in schools. The issue was due to come up in September 2019, but was postponed to September 2020, and then Covid came along. The principle is good, but the content of LGBT+ education is not specified, which means that it basically gives schools a free hand. There’s also the problem that faith schools will be allowed to promote their own religious ethos, which in many cases says that homosexuality and transgenderism are sinful and unnatural. So, we really have to close those loopholes. There is still work to be done.

David Wickenden is a student at the Harvard Graduate School of Education with a focus on LGBT rights and representations in middle and high schools.