Sleeping with Strangers: How the Movies Shaped Desire

Sleeping with Strangers: How the Movies Shaped Desire

by David Thomson

Knopf. 352 pages, $28.95

DAVID THOMSON is one of our most invigorating and thought-provoking writers on film history. He’s also highly prolific, having penned more than thirty books on everything from A Biographical Dictionary of Film to an entire volume dedicated to Nicole Kidman and, my favorite, The Moment of Psycho: How Alfred Hitchcock Taught America to Love Murder.

Thus I was eager to crack open his latest book, Sleeping with Strangers: How the Movies Shaped Desire. Indeed I had heard that Thomson was working on an epic exploration of queer figures within cinema and their considerable influence. That trajectory, as it turns out, got sidelined as he was writing and researching the book: The #MeToo movement exploded, and the author found himself caught up in analyzing some of the most sexually compelling images of both men and women, and how they shaped his own desires, as well as our collective hang-ups about sexuality and gender.

Thomson points out that Freud published his most influential volume, The Interpretation of Dreams, in 1899, which was four years after the Lumière Brothers began screening their work in Paris. Thus the birth of cinema is caught up in psychoanalysis, and film theory as we know it owes a great deal to Freud. Many film theorists have argued that the act of watching a film is akin to being in a dream state, and Thomson agrees. Indeed he seems to be exercising some sort of talk therapy in this book, as if reclining on a pyschiatric couch while recalling moments in his life that were shaped by things he witnessed and experienced on the big screen.

His mission in the first half of the book is to demonstrate just how queer cinema has been historically, especially the Tinseltown variety. “The story of gayness in Holly-wood and our movies,” he argues at one point, “has as much to do with the in-security of American heterosexuals as with the liberation of homosexuals.” The author points out that many gay people worked quietly and not so quietly in creating the classic movies, and there are possible queer readings of many films that make no overt references to homosexuality.

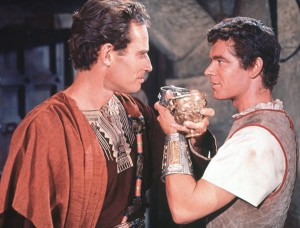

Thomson has an inviting writing style, but many of his observations will seem almost quaint to the LGBT reader who loves movies, who has long known that much of what was intended to be queer on screen was censored and thus has to be deciphered (e.g. Tennessee Williams’ films). Did you know Cary Grant is thought to be gay or bisexual? Did you consider that there was a homoerotic subtext to Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid? Did you know that screenwriter Gore Vidal and star Charlton Heston had a feisty debate about whether or not there was a gay subtext to the chariot race in Ben Hur? You get the idea. While it’s always great to hear from a straight ally, these observations and analyses have been discussed before, with some of Thomson’s work recalling the writing of Richard Dyer and the late Alexander Doty.

The book has understandably come under some fire for the way the author delves into the #MeToo movement and shares his thoughts on the act of looking and its impact on the audience. The debates over the connection between what we see onscreen (lots of violence and sex and sometimes a combination of the two) and our off-screen behavior have raged for decades, and Thomson is honest in his own discussion about what that means for him, both personally and professionally. He has, after all, spent countless hours ogling stunning women who were filmed precisely so they could be ogled. He makes the Freudian implications clear in pointing out that “movies are the industrialization of murder and orgy as regular human fantasies.”

Thomson stumbles when he gets into his close friendship with James Toback, a filmmaker who came under fire in late 2017 when hundreds of women accused him of sexual harassment or outright assault. It was these revelations that led Thomson to change the focus of the book, and to his own honest discussion of how the movies have often catered to horny heterosexual men. Before you know it, he’s shifted into what feels like an apology for Toback, who, Thomson insists, has turned things around and has a new project on the horizon. This section is unfortunate, despite its honesty. Film buffs will nonetheless want to read Sleeping with Strangers, an analytical book that somehow maintains a dreamlike quality. Given the insanely messy connections between the sexual images we consume and our actual sex lives, all of us could probably use more time on the couch (this author included).