Possession Obsession: Andy Warhol and Collecting

Edited by John W. Smith

The Andy Warhol Museum

160 pages, $39.95

Andy Warhol

by Christopher Makos

Charta. 412 pages, $29.95

Andy Warhol: Drawing and Illustrations of the 1950’s

Distributed Arts Publishers

112 pages, $9.95

Keith Haring: Heaven and Hell

Edited by Götz Adriani

Hatje Cantz Publishers. 200 pages, $45.

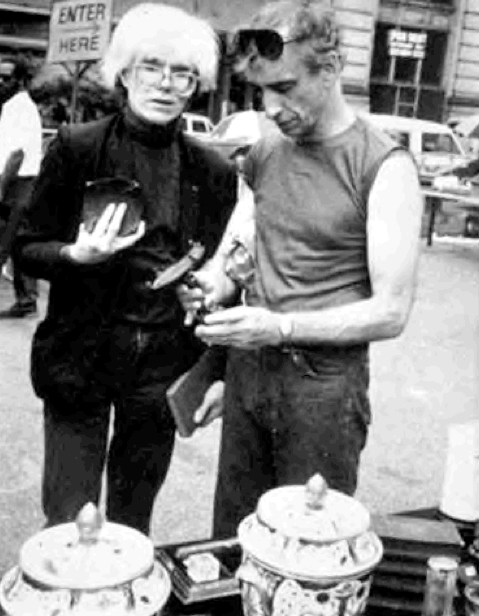

ANDY WARHOL and Keith Haring met in person in 1983, near the end of the senior artist’s career but still in the flowering of Haring’s all-too-brief life (he died in 1990). What seems to have excited Warhol most about the younger artist was his plan to open a retail outlet for the sale of his work. The Pop Shop opened its doors in 1986 and sold Haring-designed merchandise that featured his artwork on T-shirts, posters, and even inflatable animals, among other commercially produced items. Warhol had strongly encouraged Haring to pursue this enterprise, which, after all, was entirely consistent with Warhol’s own conflation of “high” art and “low.” What’s more, Warhol was at this stage of his life increasingly indulging his obsession with commercial culture by collecting its artifacts in great heaps, culling the dealerships of New York as a daily ritual: in short, by shopping.

Among the recent books in the never-ending supply of Warholiana are the beautiful Possession Obsession, and two small, quirky ones, a book of photographs of Warhol by Christopher Makos that includes virtually no text, and a book of “drawings and illustrations” that reproduce Warhol’s early illustrations as a commercial artist. Keith Haring, who was much more widely respected in Europe than in the U.S., is also the subject of a new work, a handsomely produced book entitled Keith Haring: Heaven and Hell. All four of these books have something of interest to offer both aficionados of pop art and pop culture and to those yet to be initiated into the worlds of these two artists.

Possession Obsession is actually the gallery catalog for an exhibit of the Andy Warhol Museum that recently traveled to the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD) Museum—and a fascinating collection it is. “Possession Obsession: Objects from Andy Warhol’s Personal Collection” consists of some 300 objects recently brought together from the 10,000 items that Warhol collected during his life, notably in his later years. These had been auctioned off in 1988, a year after Warhol’s death, because the artist had left no provision for them in his will. At the risk of reeling off a laundry list of the kinds of items he collected, the Providence display included: cookie jars, Art Deco silver tea services, Fiestaware, an 1840 Gothic Revival side chair, posters, American Primitive art, World’s Fair souvenirs, a vast collection of Native American Art from the 19th century, and many other far-flung categories of antiques, collectibles, and memorabilia.

This exhibit was the first attempt to explore the role of “collection” in Warhol’s art and life and to focus on those areas in which Warhol—who went shopping every day of his life—had a sustained interest. He housed his collection not at the Factory but in his home on East 66th Street, which at the time of his death, said essayist Michael Lobel, “was so crammed with stuff” that Warhol was living mostly in his bedroom. At one time he had a plan for “Warhol Hall,” a gallery cum gift shop cum flea market, but nothing ever came of it. Observed essayist Jonathan Flatley, Warhol also collected “a range of things no one else pursued,” objects stored in his 600 “Time Capsules,” which were boxes that Warhol “continually filled with traces of his everyday life”—objects that could range from mail to porn (or “physique”) magazines to movie ticket stubs and the infamous half-eaten pizzas, not to mention thousands of hours of audiotapes of his friends at the Factory.

Andy Warhol: Drawing and Illustrations of the 1950’s, a tall, slender volume, is a charming collection of Warhol’s art from his early professional life, accompanied by an essay by Ivan Vartanian, “Invention of an Artist.” While marred by a number of unfortunate spelling errors, this book nicely recaps Warhol’s artistic roots in the commercial art world at a time when he was considered the “inexpensive version” of artist Ben Shahn. By 1964, this aspect of his career was all but over. Works reproduced in this book range from pen-on-paper nude males, apparently irony-free angels, flowers, and voluptuous female nudes worked in ink or gold leaf; fanciful wild animals for Glamour magazine, Christmas card designs for Tiffany, and many drawings of shoes for I. Magnin.

It was Christopher Makos who introduced Warhol to Keith Haring in 1983, and Makos has now produced a hefty flip book of photographs of Warhol called Andy Warhol, a book comprised entirely of uncaptioned photographs save a brief introductory essay entitled “‘Altered Image,’ Altered Images.” Makos’s involvement with Warhol goes back a number of years: in 1977 he published a book of celebrity photographs called White Trash, and the book caught the artist’s eye. Warhol purchased 1,000 copies of the book and asked Makos to autograph each for his Time Capsules. This book begins with Makos’s conception of Warhol as a latter-day Rrose [sic]Selavy, who was Marcel Duchamp’s feminine alter ego when he was photographed by Man Ray in 1921, during their collaboration on conceptual photography. It should be noted that Miss Selavy was infinitely more attractive and better dressed than Miss Warhol, at least to this reviewer’s eye. Warhol appears in 349 black and white photographs in a variety of wigs, made up, and wearing either a towel or a shirt and tie.

Warhol’s best-known work is not, of course, his collection of objects or his drag portraits, but rather the Pop Art that incorporated images from popular culture—soup cans, Marilyn Monroe, news reports of car crashes—into the formal space of the oil painting. It was this Warhol that exerted such a profound influence on the next generation of artists, including Keith Haring, who was born just thirty years after Warhol and whose work takes for granted the legitimacy of appropriating material from popular culture. Like Warhol, Haring drew indiscriminately from this culture—from album covers and graffiti on subway walls, from Catholic kitsch and gay pornography, you name it—in his work.

Haring’s brightly colored dogs and babies radiating rays of light are instantly recognizable, and he is also remembered for his Silence = Death composition from 1989, a pink triangle filled with silver figures, and his logo for National Coming Out Day, in which a genderless figure is seen stepping quickly from a closet door. Haring helped organize the first “Art against AIDS” exhibition and was 31 when he succumbed to AIDS-related complications in 1990. Keith Haring: Heaven and Hell includes several brief essays by mostly admiring European and American art critics. Giorgio Verzotti’s essay, entitled simply “Eros,” uses the phrase “phallocentric universe” to describe Haring’s art, and I agree that this phrase succinctly summarizes much of his work. But however filled with penises, flaccid and otherwise, this universe undoubtedly is, there’s also room for throbbing intestine-like creatures, writhing serpents, apocalyptic visions reminiscent of an acid trip gone terribly awry, a devastating satire on the Ten Commandments, and even the occasional multi-breasted woman.

Keith Haring: Heaven and Hell is the exhibit catalog from the Museum für Neue Kunst in Karlsruhe, Germany. The artwork, known for its bright colors and contrasts on a flat plane, is beautifully reproduced, though it will certainly not be to every reader’s taste. A few of the essays suffer in translation, making them somewhat inaccessible, but each writer captures a different aspect of Haring’s work—his eroticism, his disdain for religion, notably Christianity, his artistic style—and all cover uniquely interesting territory. The book also includes a comprehensive timeline of biographical and exhibition data. This is an important entry in the small but growing Keith Haring œuvre.

While firmly rooted in mainstream Protestantism, Pennsylvania-born Haring had developed a passing fancy in his teen years for the Jesus Saves movement, and as an adult became deeply mistrustful of the church. This explains, notes essayist David Galloway, his prolific use of angel and devil characters, bleeding hearts, cross or X marks, and other staples of Christian iconography. When he was commissioned to depict the Ten Commandments at Bordeaux’s Musée d’Art Contemporain in 1985, he couldn’t remember them all. He arrived in Bordeaux three days before the exhibit was set to open, and had to ask for a Bible to brush up on the commandments and their order.

In the February, 1987, entry in his journal (Keith Haring Journals, Penguin, 1996), Haring said that Warhol was “the personification of New York. It is hard to imagine what N.Y. will be like without Andy. How will anybody know where to go or what is ‘cool’?”