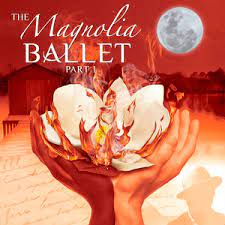

“ARE YOU a Mitchell man, or are you a faggot?” demands a father, shouting in the face of his teenage son. It’s a chilling, heartbreaking question that’s repeated throughout Terry Guest’s new play, The Magnolia Ballet, Part 1. The work by the Chicago-based playwright who grew up in the South is a lyrical, tightly choreographed play that’s getting a rolling world premiere. It opened in Chicago in early 2022, had a second showing at Williamston Theatre in Michigan in October, and will get a third premiere in Detroit in June 2023. The latter two productions are sharing a director, technical staff and two of the four actors.

The Williamston production was stunning, leaving many in the audience clearly affected as they gave the ninety-minute show a standing ovation. Guest, himself a gay Black man, has written a play that makes no apologies or accommodations to polite sensibilities, and he isn’t concerned with making those who are uncomfortable any less so.

Set in modern-day Georgia, the action moves back and forth through the generations, as far back as the slave ship that brought over the Mitchells’ ancestors.

Four actors tell the story, often taking on multiple characters and often addressing the audience directly. Stefon Funderburke is Z, a self-confident young man who is earnest and eloquent, even if he often struggles to communicate with his father. Scott Norman plays the father, Ezekiel, a man who cannot, his son explains, show physical affection because his father could not show physical affection, because his father could not do so, because for his father it was not safe to do so. But Norman infuses him with a highly animated physicality, telling the story with his entire body to reveal a man who clearly loves his son but is stuck in a place of toxic masculinity that he learned as a survival strategy. Norman also takes on the role of the white supremacist father to Z’s best friend Danny Mitchell—the two families share a last name, indicating that one may once have owned the other. He tells the audience that he knows they’re going to struggle to suspend disbelief and see a Black man playing a white character. Timothy Hackbarth plays Danny Mitchell, the pot-smoking teenage descendent of a line of white supremacists, who’s here to remind us that white supremacy is not a historic relic. Jesse Boyd-Williams poetically played the role of the play’s ghosts, apparitions that embody the past and demonstrate how the haunting gaze of history powerfully affects the current generation.

The Magnolia Ballet leans hard into its theatricality, combining dance, poetry, percussion and spectacle. The language is musical and compelling. Marsae Mitchell’s choreography tells a haunting story through such moments as a ring shout in which actors in chains dance on a slave ship, or Ezekiel giving his son a haircut. The set is in ghostly colors with timbers framing a house, somewhat askew, bordered by hanging moss. Wooden planks compose the stage floor with a hole in the middle representing the waters of the marsh that the Mitchells live on. Each element, along with the light, sound, and props, works in tandem to heighten the poetry of the play, the intensity of the story being told.

Guest raises many questions and only hints at answers. What does it mean to be Black and queer? Is it possible to escape the heavy chains of history? Can a white boy ever truly love a Black boy without acknowledging and understanding white supremacy? While it can be painful to watch at times—and the deliberate use of such slurs as “nigger” and “faggot” intentionally causes discomfort—it is ultimately a story of love between a father and son.

The Magnolia Ballet is an intensely American, intensely human story told with great poetry and compelling imagery. As for the demand of the father to his son, Guest provides his take on whether one must choose between a mythic heritage and acceptance of one’s sexuality and personhood.

Bridgette M. Redman is an independent arts writer and travel journalist.