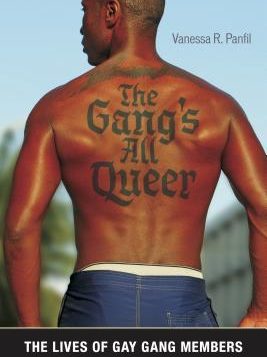

The Gang’s All Queer: The Lives of Gay Gang Members

The Gang’s All Queer: The Lives of Gay Gang Members

by Vanessa R. Panfill

New York University Press

289 pages, $28.

THE KIDS loved going AWOL every now and then from their group home. Sometimes singly, or more often in pairs, some boys would take off after school on Friday and head to nearby Hollywood. They would meet up with other gay youth and young adults (mostly runaways or homeless) to turn tricks, shoplift some clothes and snacks, get high, and party. The “fishy” boys (their term for the effeminate ones) or “transies” (their slang for transgenders) would meet up with their trans “mothers” for guidance on passing as a woman, hormones, silicone augmentation of breasts and hips, and managing sex work. Even though many had experienced dangers—including arrests, muggings, kidnappings, threats with weapons—the thrill of independence, risky sex, and life in the fast lane was often too alluring to give up. The adults they met on the street—the trans sex workers, the hustlers, the pimps—were role models of fun, freedom, self-sufficiency and fierceness.

I saw the kids the next week (or after a few months in juvenile hall) when they returned on their own or were brought back by the police. I was one of two child psychiatrists working at a non-profit agency dedicated to LGBT adolescents in six group homes for minors and in transitional-living apartments for young adults. Demographically, the vast majority came from low income, inner-city Latino and African-American families. This was not the Hollywood Glee version of cute gay kids with gumption. These were LGBT kids who had been abused, neglected, or abandoned. Like other traumatized kids, they could be defiant, rude, loud, and fighting constantly—with staff, teachers, family, school peers, but mostly among themselves. A sideways glance, an unacknowledged greeting, or flirting with someone else’s boyfriend could instantly lead to screaming, scratching, and a full-blown cat fight, to the delight of their peers.

So it was with a sense of wry nostalgia that I anticipated reading Vanessa Panfil’s The Gang’s All Queer: The Lives of Gay Gang Members. Unless inner-city gay youth are vastly different in Columbus, Ohio, from those in Los Angeles, I expected to hear some familiar stories. Overall, Panfil did not disappoint, as she let her informants give voice to their lives and concerns.

Panfil is an assistant professor in the Department of Sociology and Criminal Justice at Old Dominion University in Norfolk, Virginia. She is the co-editor, with Dana Peterson, of the Handbook of LGBT Communities, Crime, and Justice (Springer, 2014), an anthology of new work on “queer criminology,” about LGBT criminal offenders and their interactions with the police and the justice system. Although Panfil has since written about women in gangs, the present book (based on her 2013 dissertation from SUNY-Albany) is focused on 53 young adult “gay gang- and crime-involved men.” The vast majority (46) were black or biracial black, with five white and one Latino informant.

Given the racial imbalance of the sample, it might have been better to dedicate the monograph to the African-American men. Although the discussion of gay men’s involvement in white neo-Nazi gangs is fascinating, it is based on too few informants compared to the rest of the material. Panfil focuses on gay identity formation and presentation in a hostile urban, black culture, and different strategies for defense and resistance. The criminological angle is the participants’ involvement in unlawful activity and a number of diverse groups that lie beyond conventional gangs dominated by straight men. Panfil is meticulous in getting her informants to explain the composition and structure of their multiple group affiliations. Some of these had a quarter to a half of LGB members, which Panfil classifies as “hybrid gangs.” The small groups that included only gay members she labels “gay gangs.”

Considering how frequently Panfil protests that “gay gangs” are “real” gangs, it is clear that she constantly faces this objection in academic circles. She spins this as a matter of incredulity on the part of LGBT or criminological audiences that gay men, usually portrayed as victims, could be the perpetrators of crime, let alone form their own criminal gangs or gain admission to mainstream gangs. The latter are typically portrayed in the media (and apparently in criminological literature) as hyper-masculinist and homophobic. Panfil, however, documents that while this is generally true, it does not mean the “straight” gang members are exclusively straight men. “Straight gangs” can include some women and MSMs (men who have sex with men).

Aside from gang-related violence and crimes, Panfil’s gay informants engage in a range of illegal activities: sex work or “escorting,” drug sales, theft, and financial crimes or “crafting” (e.g., returning stolen merchandise, credit card fraud, check cashing). In her analysis, the hybrid gangs do not engage in violent initiation rituals (“jumping in”) or “sexing in” female initiates (forced sex with most of the male gang members). The hybrid gangs “foster an environment that emphasizes relationships.” Panfil and her informants largely confirm that “straight gangs” foster an aggressively masculine, sexist, and homophobic group ethic. While they might have gay male members, these individuals know to remain closeted lest they become an affront to the street credibility of their gang. From my own experience, masculine lesbians (“studs” as they call themselves in L.A.) are more likely to be out in a conventional “straight” gang than is an MSM. Of course, the sexual identity (let alone sexual behavior) of “straight” male gang members can be all over the place; many of Panfil’s informants report regular sex with “straight” gang brothers.

I too question the validity of Panfil’s “gay gang” label, which relies on what seems an overly broad definition of a “gang”: “they are durable, street-oriented youth groups whose identity includes involvement in illegal activity.” By that definition, all of the young men I cared for were in gay gangs. However, of the hundreds of teen males that I worked with, only a couple reported gang affiliation. Among the women, on the other hand, many boasted belonging to a gang (often an all-female one) and had the tattoos to prove it. Panfil herself notes throughout that many of her informants rejected the gang label and preferred instead to call their social group a “crew,” “posse,” “clique,” or “family.” She frequently quotes informants distancing themselves from the “gang” label. Jeremiah, who belongs to the Firing Squad “clique,” clearly distinguished his group from gangs:

We’re not out here standin’ on corners, we’re not out here shootin’ people for no reason, we’re not out here battlin’ people over turf, or anything like that, and we don’t have anything to claim. Like, we’re not out here tryna prove somethin’, umm, we call ourselves a clique because we’re around each other 24/7 and we always have each other’s back, but at the same time, I feel like gangs are territorial, so they feel like they have to get somethin’, or they’re out there for somethin’. We’re not out here to prove anything, or anything like that, we don’t have anything to prove, we’re just out here livin’, and helpin’, and supportin’ each other.

Jeremiah’s statement not only captures why his gay group is not a gang, but also much of what Panfil tries to elucidate about “gay gangs” as opposed to “straight gangs.” According to Jeremiah, Panfil’s other informants, and everyone I surveyed at the clinic where I currently work in South Los Angeles, “real gangs” engage in deadly violence in defense of drug dealing territory or the defense of their own reputation. Gay groups (even in Panfil’s sample) are not armed and have no territory to defend. They may engage in plenty of illegal activity, including minor drug sales, shoplifting, and sex work. They also engage in fights among members of different cliques, often over small slights, drama, boyfriends, etc., but they quickly forget what the trigger was. Gay cliques are a vital support system for gay men developing their sexuality and sexual identity in overwhelmingly sexist and homophobic environments, which are even further distilled in “real gangs.”

Panfil’s other lengthy quotations throughout the volume also capture tensions between an acceptance of gay identity that the gay groups foster, a sexist contempt of effeminacy, and a respect for a hysterically aggressive femininity. Most of the gay men outside of the safety of their clique have to hide any traces of what they perceive as femininity or “fishiness”: a swishy gait, feminine hand gestures, high-pitched voice, makeup, or skinny jeans. Many dated women as a “cover-up,” and almost a fifth of them had fathered children. Some of the guardedly feminine guys vehemently reject the idea of dating fem guys, and many masculine guys prefer the same: “I want a dude that look like a dude, act like a dude. Cuz if I want a girl, I can get a girl. I was bisexual once,” boasted one participant. On the other hand, they have a certain respect for, even awe of, flamboyance. “Vogue” dancing—especially in competitive gay balls— remains as vibrant in today’s Cleveland as in 1980s New York (as depicted in Jennie Livingston’s documentary Paris Is Burning, about vogue “houses”). Aggressive femininity (or “fagging out”) can also be used as a defensive strategy in reaction to homophobic threats: for example, going off loudly on someone to intimidate them, or basically to emasculate a bully. As one informant described responding to being called a “fag”: “I’m gonna fag out on you so everyone can know that you’re the punk.”

The Gang’s All Queer’s grounding in criminology leads to extensive discussion of the illegal activities or “underground economies” of the participants. Three-fourths had been arrested; over half had been incarcerated. The majority of the sample had engaged in sex work, and a majority had sold drugs. A third had engaged in both. However, a fifth reported neither of these activities, and almost a half of the sample engaged in some legal work. An interesting finding was that straight gang membership was associated with drug sales, while gay gang membership was associated with sex work. Panfil details how the gay cliques help break members into gay sex work—a process I was familiar with from work at LGBT group homes. She builds on extensive prior research that documents inner-city, minority LGBT youths’ high rates of drug use, HIV risk and infection, and incarceration. Her informants relate their ambivalence, rationalizations, and even their disdain for illegal activities (particularly “escorting”), but as they (and other researchers) point out, with truncated education, limited job opportunities, and widespread discrimination (against minorities and gays), these illegal activities are an easier way of making survival money than minimum wage jobs.

Panfil’s analysis betrays her own deep ambivalence: she argues for the importance and legitimacy of criminological research on LGBT populations, yet she is genuinely attached to her informants. She presents an ethnography about inner-city, gay resilience and survival rather than about criminality. Unlike my work as a clinician or Panfil’s earlier activity at a LGBT youth center, Panfil’s role in this research was not to intervene or redirect. However, I am left wondering how these young men have ended up, almost a decade later, and whether their interactions with the “butchy white girl” inadvertently touched their lives for the better. Given the affection with which Panfil presents the richness of their world, I’m sure she must wonder too.

Vernon Rosario is a child psychiatrist with the Los Angeles County Department of Mental Health and an associate clinical professor of psychiatry at UCLA.