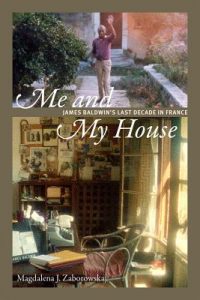

Me and My House: James Baldwin’s Last Decade in France

Me and My House: James Baldwin’s Last Decade in France

by Magdalena J. Zaborowska

Duke University Press. 408 pages, $28.95

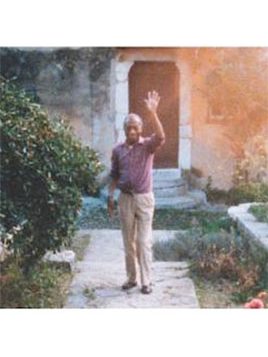

IN ME AND MY HOUSE, Magdalena Zaborowska reconstructs and analyzes the last decade of James Baldwin’s life when he lived in St. Paul-de-Vence, a small village in the south of France. For sixteen years, from 1971 to 1987, he resided in a house nicknamed “Chez Baldwin,” which became a metaphor for themes of domesticity and dwelling. But this was also the period in which Baldwin explored black gay sexuality, among numerous other topics, in his novels If Beale Street Could Talk (1974) and Just Above My Head (1979).

Baldwin’s late writings go in a different direction from his earlier works, influenced in part by his reading of a number of black women authors, notably Toni Morrison, Alice Walker, Maya Angelou, Gwendolyn Brooks, Ann Petry, and Paule Marshall. Photographs taken of Baldwin’s personal library reveal that he owned books by all of these authors. Writes Zaborowska: “[His] œuvre and revolutionary depictions of domesticity inspired and gave legitimacy to the black, gay, and queer movements.” The author’s earlier critical studies of Baldwin’s late works provide a solid footing for this book, for which she also made use of interviews with Baldwin’s friends and lovers as well as unpublished letters and manuscripts.

Much of Baldwin’s writing is autobiographical. He tells of the physical abuse that he endured from his stepfather and the poverty that he and his large family experienced, a theme that appears frequently in his early works. A white elementary teacher, Orilla “Bill” Miller, recognized something exceptional in the young Baldwin. She took him to movies and plays and sometimes came to his home bearing clothes, cod-liver oil, and books. As Miller was a white woman, his stepfather knew better than to send her away.

Zaborowska provides an overview of Baldwin’s literary influences, including several writers from the Harlem Renaissance who wrote about home as a place of conflict, a place where blacks’ fates are subject to racist laws, prejudice, and violence. One of his mentors, Richard Wright, helped Baldwin to get a fellowship, and the money was used for a trip to Europe; however, the two had a falling-out over a review of Native Son for which Wright never forgave Baldwin. Writes Zaborowska: “Queers and their ancestors by any other name have lived in houses and created families for as long as the rest of humanity, but as scholars have not paid much attention to this phenomenon, Baldwin’s insertion of sexual history, domestic practices, and representations of household into his works amounted to a pioneering, prophetic, revolutionary act.”

The house was partially demolished in 2014; on her last trip to St. Paul-de-Vence, Zaborowska found that little of the great author’s domicile has been saved. Thus pictures of Baldwin’s home in this richly illustrated book come in two stages of demolition: partial and final. Although Baldwin wanted to make his home a space for writers upon his death, the house went to his brother when he passed, and from there it was surrendered for the money owed on the mortgage.

In the final chapter, titled “Black Lives Matter,” Zaborowska considers the role that racism plays in the valuation of relics. She juxtaposes Rosa Parks’ home in Detroit, which was spared the wrecking ball only because a German citizen paid to have it dismantled and reassembled in Berlin, with the fate of Chez Baldwin. Meanwhile, the Beinecke Library at Yale considers Walt Whitman’s reading glasses a precious artifact to be locked under thick glass for all time.

________________________________________________________