OVER THE PAST DECADE, we’ve seen a great deal of progress on HIV/Aids in the U.S. Data released by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in late 2015 indicate that diagnoses of HIV in the U.S. declined significantly over the last decade. Rates of new HIV diagnoses for the general population dropped nineteen percent between 2005 and 2014, from about 49,000 new HIV diagnoses each year to about 40,000. With some populations hard-hit by HIV, we saw even greater improvements: new diagnoses were down 42 percent for mostly heterosexual black women, down 35 percent for heterosexual women and men of all races, and down 65 percent for people who inject drugs. White gay and bisexual men experienced an eighteen percent decline in new diagnoses from 2005 to 2014.

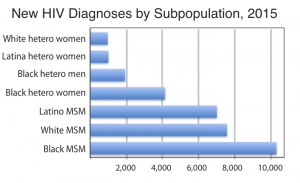

However, black and Latino gay and bisexual men actually saw an increase in HIV diagnoses of 22 percent and 24 percent, respectively, over the same time period. New diagnoses for thirteen- to 24-year-old black men who have sex with men (MSM) were up 87 percent from 2005 to 2014. Even though white gay and bisexual males outnumber their black counterparts by a ratio of four or five to one, in 2014 about 10,000 black MSM of all ages were diagnosed with HIV compared to about 8,000 whites. Transgender women also face a disproportionate burden of HIV, with blacks experiencing the highest rates of infection.

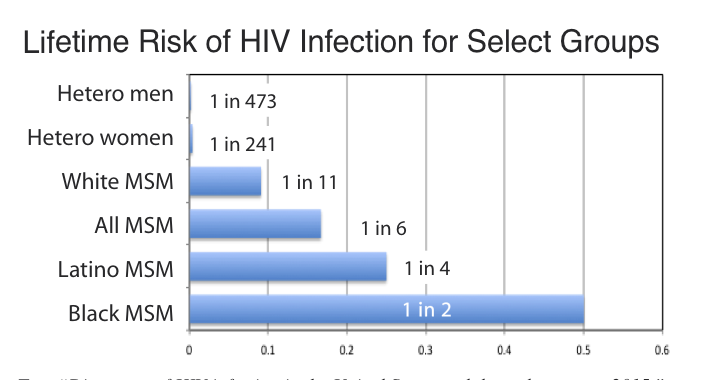

At the 2016 Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, the CDC released data showing even more alarming racial disparities between different categories of gay and bisexual males in the U.S. If current HIV diagnosis rates persist, MSM overall have a one in six chance of becoming HIV-infected at some point in their lives, but for white non-Hispanic men the odds are one in eleven, for Latino men one in four, and for black men one in two.

Given the moral narratives often associated with HIV, it’s important to note that higher rates of HIV among black MSM are not due to higher rates of risky behaviors. Black gay and bisexual men have fewer sexual partners than their white counterparts and are less likely to use substances before sexual activity that might promote risk-taking behavior. The factors that make black men more vulnerable have built up over decades and are directly related to lower rates of health insurance and access to health care. They include higher rates of undiagnosed and untreated sexually transmitted infections which, in turn, can facilitate HIV transmission. Black MSM also have a higher rate of undiagnosed HIV infection and, even when diagnosed, they tend to have lower rates of antiretroviral treatment than do white MSM. As a result, there is a greater per capita pool of non-virally suppressed HIV-positive men in black men’s social and sexual networks.

There are at least three steps we should take to reduce the HIV burden among black gay and bisexual men. First, we need to improve health care for them. A study published last year in The American Journal of Public Health found that 29 percent of a sample of 544 black MSM experienced stigma related to race and/or sexual orientation in health care, and 48 percent expressed mistrust toward the medical establishment (Eaton, 2015). Even as we applaud the expansion of health care access brought about by the Affordable Care Act—which disproportionately helps blacks and Latinos, LGBT people, and people living with HIV—we must ensure that health care providers are trained to provide culturally competent and affirming care to black gay and bisexual men.

Such health care includes discussing pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV prevention and encouraging black gay men to consider this option. Non-Hispanic blacks comprised 45 percent of those newly diagnosed with HIV in 2013 (Dasgupta, 2016). While about 80,000 people in the U.S. were using PrEP by the end of 2015, its adoption by black and Latino gay and bisexual men, young people, women, and Southerners has lagged. Of those whose race/ethnicity could be identified, 74 percent were white, ten percent black, twelve percent Latino, and four percent Asian (Rinehart, 2016).

“Lifetime Risk of HIV Diagnosis by Transmission Group.” This chart from the CDC highlights the disproportionate odds of HIV infection for gay men and especially for gay men of color.

Researchers and HIV providers in the South, New York, and elsewhere have piloted promising prevention approaches with young black gay men (Van Wagoner, 2016; Cahill, 2013). These include an HIV prevention game with avatars designed for black adolescents in rural Alabama; working with black churches to reduce HIV stigma and promote HIV screening, prevention, and treatment interventions; and “Men’s Health Monday”—a clinic open after university sporting events to screen all men for STIs, including HIV. This approach enables MSM who are not openly gay or bisexual to be tested and offered risk reduction counseling.

Second, we need a renewed focus on educating young people about HIV. The continuum of care for adolescents and young adults in the U.S. has major gaps. Only 41 percent of youths thirteen to 29 years old who are HIV-infected are diagnosed. Only 62 percent of those diagnosed with HIV gain access to medical care within twelve months of their diagnosis; of those only 54 percent are virally suppressed. The bottom line is that less than six percent of HIV-infected youth in the U.S. are virally suppressed (Zanoni, 2014). This is a major factor in the continued transmission of HIV among young people.

Lack of knowledge about where to get tested and fear that family will find out are major barriers to adolescent gay males getting screened for HIV. In a sample of gay and bisexual males age fourteen to eighteen, 43 percent did not know where to access testing, and 61 percent claimed that family or friends finding out about it was an important barrier to testing (Phillips, 2015). Fear is also a common deterrent for condom use: 92 percent of sexually experienced gay and bisexual male youth feared their parents would discover that they were having sex if they possessed condoms, and 65 percent feared embarrassment when buying condoms. High cost, inconvenience, and spontaneous sex were also common reasons for non-use of condoms (Mustanski, 2014).

There is a lack of comprehensive sexuality education in schools. Even in liberal cities like Boston and New York, sex education has started only within the last few years, and in many parts of the country there is none at all. Eight states, mostly in the South, have laws prohibiting any mention of homosexuality or same-sex behavior that is not condemnatory. In many school systems, principals have a great deal of autonomy, so there is significant variation from school to school in whether young people learn how to protect themselves against STIs and HIV.

Third, we must support efforts to expand access to health care, especially in the South. Of three million Americans who are too poor to afford subsidized marketplace insurance but not poor enough to qualify for Medicaid, 89 percent live in the South. Several conservative states have recently expanded Medicaid, including North Dakota and Louisiana. As of early 2017, 31 states had embraced the expansion of Medicaid to all adults up to 138 percent of the federal poverty level. Efforts to further expand insurance and health care access through Medicaid expansion or another approach would disproportionately benefit black Americans, half of whom live in the South, and could help black gay and bisexual men and black heterosexuals gain access to the preventive health care they need and deserve.

As this issue of The Gay & Lesbian Review goes to press, there is uncertainty about the future of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and a key component, Medicaid expansion. The ACA requires insurance providers to offer insurance for all who apply and to offer comparable rates to everyone without regard to preexisting conditions such as HIV infection. As of 2013, only seventeen percent of the estimated 1.2 million Americans living with HIV had private insurance, and thirty percent had no health insurance (Cahill, 2015). Many of the twenty million newly insured under the ACA are insured by Medicaid, including thousands of people living with HIV. Blacks, Latinos, and LGBT people have benefited disproportionately from the ACA’s expansion of insurance and health care access. Maintaining access to affordable health care for people with HIV and other chronic conditions will continue to be a major health equity concern for the foreseeable future. Access to culturally competent, affordable preventive health care regardless of preexisting conditions is important if we are to reduce the striking disparities affecting gay and bisexual men in the HIV epidemic, especially gay and bisexual men of color.

References

Cahill, S, et al. “The Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program in the age of health care reform.” American Journal of Public Health, 2015, 105(6).

Cahill S., et al. “Community-based HIV prevention interventions that combat anti-gay stigma for men who have sex with men (MSM) and transgender women.” Journal of Public Health Policy, Jan. 2013, 34(1).

Centers for Disease Control sources: Press release, December 6, 2015. Fact Sheet (“HIV Among Transgender People”), April 18, 2016. Press release. February 23, 2016.

Dasgupta, S., et al. “Disparities in consistent retention in HIV care: 11 states and the District of Columbia, 2011-2013.” MMWR, Feb. 5, 2016.

Eaton L. A., et al. “The role of stigma and medical mistrust in the routine health care engagement of black men who have sex with men.” American Journal of Public Health, 105(2), 2015.

Mustanski, B., et al. “A mixed-methods study of condom use and decision making among adolescent gay and bisexual males.” AIDS & Behavior. 2014, 18(10).

Phillips, G. et al. “Low rates of human immunodeficiency virus testing among adolescent gay, bisexual, and queer men.” Journal of Adolescent Health, Oct. 2015.

Rinehart, A. Presentation at ViiV Community Summit, Fort Lauderdale, Nov. 12, 2016.

Van Wagoner, N. HIV prevention in the South; Reducing Stigma, Increasing Access. National LGBT Health Education Center, Fenway Institute. 2016.

Zanoni, B. C. and K. H. Mayer. “The adolescent and young adult HIV cascade of care in the United States: Exaggerated health disparities.” AIDS Patient Care & STDs. 2014, 28(3).

Sean Cahill, PhD, is Director of Health Policy Research at The Fenway Institute in Boston.