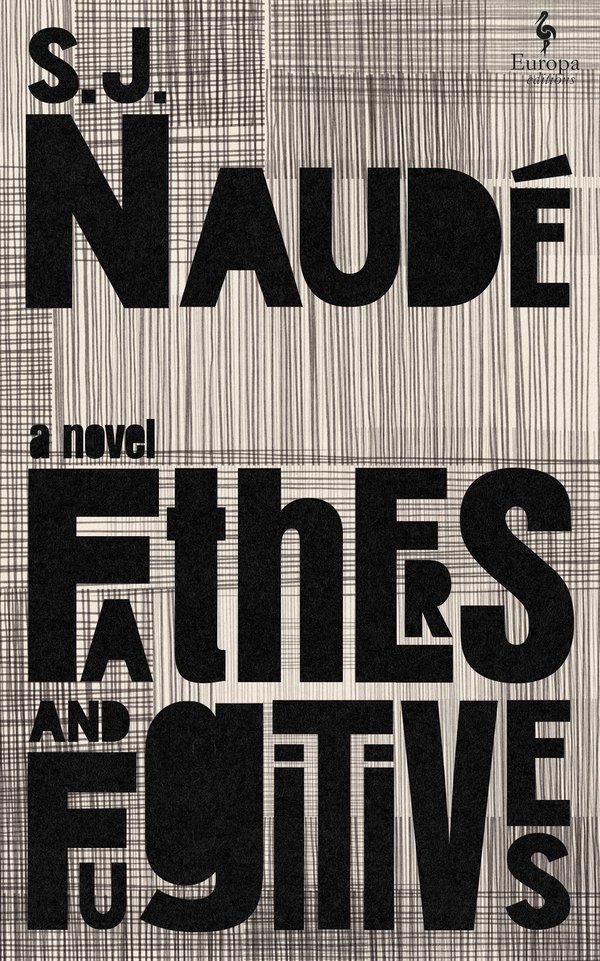

FATHERS AND FUGITIVES

FATHERS AND FUGITIVES

by S. J. Naudé

Translated by Michiel Heyns

Europa Editions. 214 pages, $27.

TRANSLATED from Afrikaans by Michiel Heyns, S. J. Naudé’s arresting novel Fathers and Fugitives is aptly titled. Absent, flawed, or destructive fathers control the action of the five-part narrative in which sons respond in various ways to paternal actions. Similarly, throughout the book, fugitives from a range of homes and regions navigate the complicated terrain of geographical and psychological displacement.

Although the five sections can almost stand alone, the first chapter, “Where the Wolves Mate,” introduces key themes. The first scene transports us to London’s Tate Modern, where the protagonist, Daniel, a South African writer living in London, meets two Serbian fugitives escaping the homophobia of their native land. Significantly, one of the Serbs pronounces the exhibit “boring” and invites Daniel to coffee instead. Daniel’s readiness to forgo an art show that he’s looked forward to hints at his preference for adventure over art and provides a rationale for the exploits to come. During this section, he and the Serbs travel from London to Germany and on to Belgrade. The apparently fatherless Serbs become increasingly dissolute and despairing. As for Daniel: “Unexpectedly he feels a yearning for Cape Town. The country that has always felt like a strange wind on his skin. And that harbors a father whose presence penetrates to even the oddest corners of the world.” That the story of the Serbs ends in the country they were seeking to escape suggests the futility of flight and the impermanence of expatriation. The link between fathers and homeland is borne out during the course of the narrative.

The second section of Fathers and Fugitives finds Daniel back in Cape Town caring for his father, who’s suffering from dementia. Having been moved to write the story of his involvement with the Serbs, he is tinkering with an essay called “When the Wolves Mate.” Daniel’s professional motivation for participating in the Serbian episode, that he has been seeking subject matter for his writing, is thus revealed. He entertains himself during the time with his father by talking to the older man about his past gay affairs, knowing that his father probably won’t understand. As he begins to talk about the episode with the Serbs, he thinks: “What a relief … to be telling the story to someone who is under no pressure to attach any meaning to it.” His gradual disaffection with the ability of art to communicate is beginning to emerge.

The second section of Fathers and Fugitives finds Daniel back in Cape Town caring for his father, who’s suffering from dementia. Having been moved to write the story of his involvement with the Serbs, he is tinkering with an essay called “When the Wolves Mate.” Daniel’s professional motivation for participating in the Serbian episode, that he has been seeking subject matter for his writing, is thus revealed. He entertains himself during the time with his father by talking to the older man about his past gay affairs, knowing that his father probably won’t understand. As he begins to talk about the episode with the Serbs, he thinks: “What a relief … to be telling the story to someone who is under no pressure to attach any meaning to it.” His gradual disaffection with the ability of art to communicate is beginning to emerge.

Upon discovering that his father is dead, Daniel takes his sea kayak and deliberately risks his life by putting himself in the path of huge cargo ships, then rowing frantically to avoid them. He may be pursuing the excitement he sought from his adventures with the Serbs as a way to stimulate his writing. But in this way he’s also struggling to assert control over his circumstances, even as outside forces, such as a codicil to his father’s will, come to control him over the course of the novel.

In order to receive his inheritance, Daniel’s father has required him to reconnect with his cousin Theon, who lives on a farm in the South African province of Free State. Back in the region where his mother grew up, Daniel comes to understand that her final words signal that she’s returned to this village in her last moments, even though she’s been a fugitive from this rural, impoverished area for her entire adult life. Although he’s required by the terms of the will to stay for only a month, the sojourn inevitably leads to more adventures. He and his cousin Theon travel to Japan seeking a cure for the rare cancer from which the child of a former farm hand suffers. While in Japan, he contemplates writing an essay on Japanese architecture called “Architecture and Death.” But events intervene, and the writing seems to get lost. In a gesture of seeking closure, he sells his father’s house in Cape Town, sells his own flat in London, and buys a small house in Kent.

Years later, the reason for his father’s codicil is revealed, deepening the motif of the need for flight. Going through his own father’s papers, Theon has discovered a letter written to his father by Daniel’s father, soon to be his brother-in-law. In this short missive, Daniel’s father disavows a drunken sexual encounter between the two men and underscores his resolve to marry Daniel’s mother. Thus his mother was not the only fugitive from the farm in the Free State; his father also had to stay away to avoid complications from his past.

After Daniel accepts Theon’s invitation to leave England and return to the farm, the theme of failed fatherhood culminates in a tragic event that catapults both men, now a couple in their sixties, back to England. All of the salient themes come together in the evocatively poetic last chapter, “The City of Fathers and Sons,” a reference to a neglected cemetery near the Free State farm. Earlier in the novel, when Daniel’s dying father asked what country they were in, he had responded: “It doesn’t matter, Dad. This country, that country. … Here is as good as nowhere. For you, but also for me.”

The momentum of Fathers and Fugitives is maintained by its elegant prose and intricate plotlines. While the thematic complexity, subtle narrative twists, and provocative imagery produce a challenging narrative, the payoff is well worth the effort.

Anne Charles lives in Montpelier, VT. With her partner and a friend, she co-hosts the cable-access show All Things lgbtq.