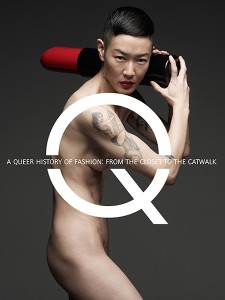

A Queer History of Fashion: From the Closet to the Catwalk

Exhibition: The Museum at FIT (Fashion Institute of Technology)

Curated by Fred Dennis and Valerie Steele

A Queer History of Fashion: From the Closet to the Catwalk

A Queer History of Fashion: From the Closet to the Catwalk

Edited by Valerie Steele

Yale. 248 pages, $50.

FRED DENNIS, senior curator of costumes at the Fashion Institute of Technology, originated the idea of looking at the fashion industry through a queer lens to establish the centrality of gay creativity to the fashion industry since the 19th century. The result is an exhibition that sets out to document the contribution of gay men and lesbians to fashion over this nearly two-century time frame, both in their capacity as fashion designers and as trend-setters who wore designs that were avant-garde for their time.

Garments designed by Dior, Yves Saint Laurent, Halston, Alexander McQueen, and Jean Paul Gaultier are high art. These designs are living embodiments of their theories about bodies interacting with one another in society and culture. These designers are justly celebrated for their ability to capture and break gender conformity for men and women. How they were able to move forward is a measure of their creativity. To figure out what these artists were up to conceptually, one has to go behind the superficial glitz of the commercial fashion scene that is the stage on which they strutted their stuff.

The range of these designers runs the gamut from cartoonish satires to top hats and men in leather and lace skirts. These are postcards from the edge, embodying a variety of people from varying classes of society, but mostly those with the wealth or savoir-faire to adopt the high style of the day. As for the designers of these fashions, at a symposium held in conjunction with the show, Fran Lebowitz, dressed in her signature designer jacket tailored by Anderson and Sheppard, was asked by co-curator Valerie Steele why so many GLBT people went into the fashion industry. Because they had nowhere else to go,†she replied. “Straights could go anywhere but gays were strictly limited. Regarding fashion through the template of the contemporaneous fashion experience enables us to comprehend just how complex an art form it is. The stylists of these sensations, of these movements, are boldly creating experiments designed for living so that all social interactions become theatrical and performative. Few people understood this as well as those men whom Pierre Balmain described as having girlish interests in dresses, who went on to create the sophisticated, fey, and funny fashions that can be found throughout this exhibit, such as Pierre Balmain’s iconic riding costume for Jean Cocteau’s 1947 play, L’Aigle à Deux Têtes. The accompanying book for the exhibition is beautifully produced by Yale University Press, but it doesn’t generate the excitement of the exhibition itself. In 248 pages, amply illustrated and featuring seven essays, the book covers a history of couture ranging from Beau Brummell to dandyism, on up to contemporary lesbian chic and activist T-shirts. Of singular note are Elizabeth Wilson and Vicki Karaminas’s contributions for their off-the-cuff concepts of what a lesbian looks like and how lesbian style has evolved since the 1980s. These had me rushing to the mirror to check myself out to see if I still qualified as a lesbian! Reading their post-modern, ahistorical analysis left me largely clueless. I was grateful for Joyce Culver’s wonderfully reaffirming and sexy photograph of a hot young lesbian in a gay pride parade wearing slicked down sideburns, a leather cap, and black bra. The major problem with these essays is that few if any references are made to fashion foremothers such as La Garçonne or Romaine Brooks’ Sapphic portrayals of women. Instead, these writers reinvent the wheel, beginning with lipstick lesbians, cross-dressers, and drag kings, as if we had no historic ground to stand upon. Providing a foundation as Valerie Steele did in her opening essay would have helped readers comprehend the bedrock for these newly fashioned lesbianisms. The book closes with a well-written and amusing autobiographical account of queer activist fashion by Jonathan D. Katz. If the show had a somewhat unfinished quality, this is perhaps because fashion itself is always unfinished, both a product and a shaper of cultural change. Cassandra Langer, a freelance writer based in New York City, is a frequent contributor to these pages.