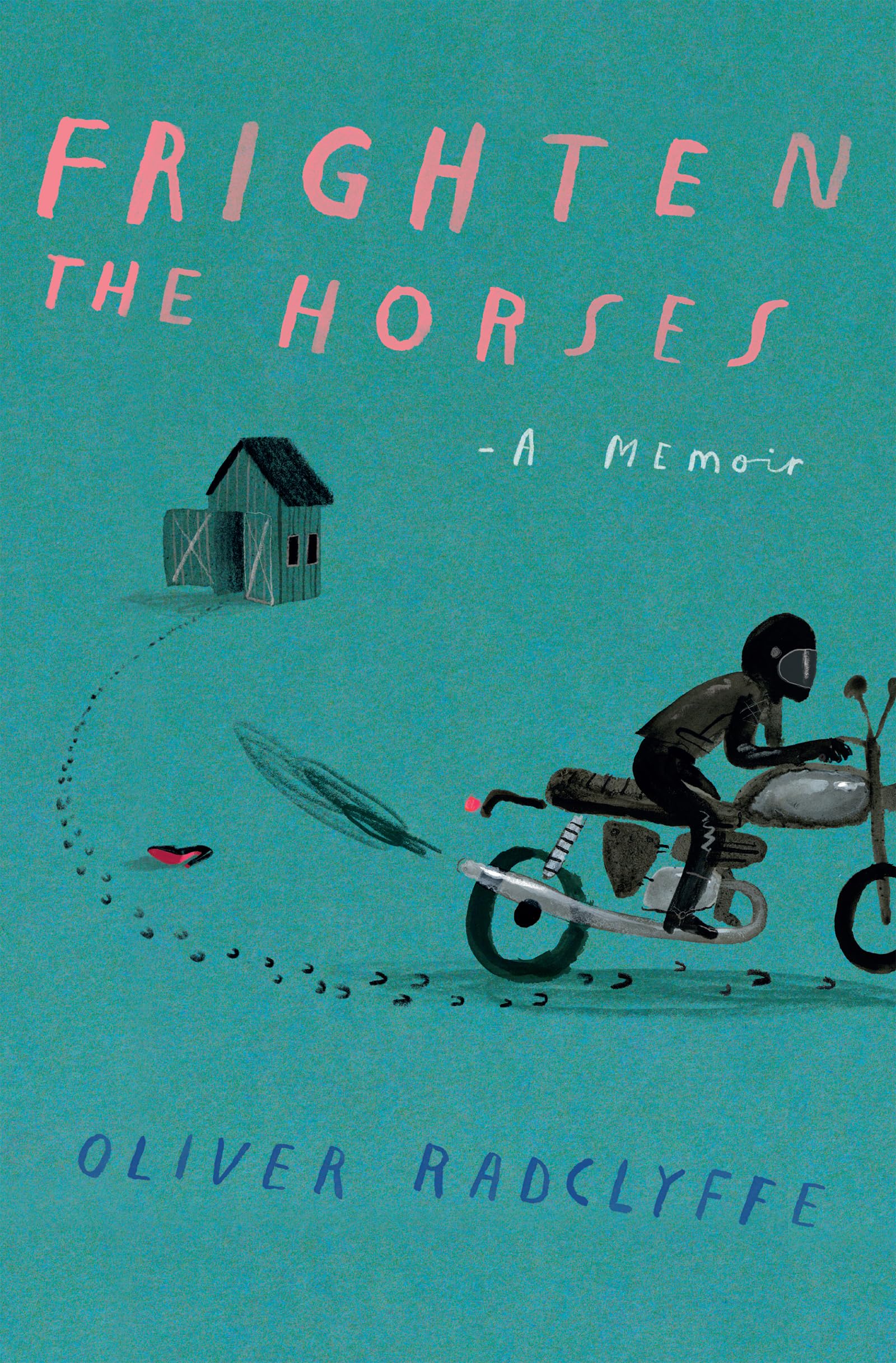

FRIGHTEN THE HORSES

by Oliver Radclyffe

Roxane Gay Books. 352 pages, $28.

NOVELISTIC AND EPISODIC, Oliver Radclyffe’s memoir Frighten the Horses is written with verve, humor, and specificity. His story begins in an affluent British family, where Oliver was raised to take his state of privilege for granted. Later in life, however, he would have to contend with the social challenges of a different kind of status: his transmasculine identity. “I’d been bound by the rules and regulations of upper-class English society since the day I was born,” he writes, “although even now in my diasporic state it is excruciating to admit this.”

Oliver’s exploration of LGBT culture and history feels anthropological as he seeks to understand his role within this multifarious milieu. He writes thoughtfully and sensitively about his encounters with several women. His explanations are consistently self-reflexive and eschew glib pronouncements. His analysis of the sensations that emerge with each interaction are comprehensively evaluated and challenged. He finds himself in Brooklyn, a place “progressive” enough for the new family dynamic: “I wondered whether these were the sort of people who might make me feel more whole.”fL

After dating several women, Oliver realizes that he’s most comfortable playing a dominant and assertive role during sex, and soon begins to imagine life as a man, which feels right despite his anxious misgivings: “A fully embodied experience not just of making love to a woman, but of making love as a man.” Oliver discovers that he has a phantom penis and becomes enamored of the trappings of being a man. Simultaneously, the realities of womanhood become intolerable: “I felt suffocated by the smell of face powder and expensive perfume, overwhelmed by the glitter of silk and lipstick and jewelry.”

Oliver writes about Charles with understanding—”This meant he hadn’t just married a lesbian; he’d married a man”—but he’s also hurt by his parents and family friends, who seem more concerned about the effect of the transition on Charles and the children than on Oliver himself. Tellingly, his parents were almost enthusiastically supportive of Oliver when they thought he was a lesbian. “Oh Daddy,” said Oliver when he came out initially as gay. “I thought you believed homosexuality was a sin.” “I did,” answered Oliver’s father. “[I stopped] a few minutes ago when I found out I had a gay daughter.”

While Oliver’s interactions within the LGBT community are revealing, his attempts to come to terms with his male identity are especially moving. “I wish it didn’t matter so much to me, but after a lifetime of feeling invisible, I was desperate to be seen.” Indeed the title of this memoir is a British expression about being discreet and not making a public display of oneself—in other words, being invisible so as not to frighten the horses.

Oliver encounters resistance from some of his female partners when he comes out to them. “I am sick of men,” says Jamie, a woman with whom Oliver was romantically involved before his transition, who had left her husband to be with a woman, ”You can’t hold me accountable if you turn into something I can’t love,” she tells Oliver.

Radclyffe’s prose is vigorously corporeal and sensory. He puts us in his body at every turn, with vivid physiological reactions to situations and insightful responses to revelations. He doesn’t just tell us about his gender dysphoria, he shows us. Every ache and flash of embarrassment, every jolt of panic and frustration, is written with phenomenological anguish, and also with great wit. “Given the choice between Virginia Woolf and Quentin Crisp, I’d rather be an Englishman in New York.” He writes poignantly and incisively about body ownership: “Who does my body belong to? Who is my body for? It’s like my femininity’s a gift I’ve been giving to other people for so long that they’ve just come to expect it, and if I take it back everyone’s going to accuse me of being selfish. What I wanted was apparently irrelevant because everyone else’s claim on my body exceeded my own.”

With tireless compassion and microscopic meditations, Radclyffe brings us through his psychological, emotional, and physical transitions. All the while he considers the impact his changes will have on his children. His journey is fueled by courage, honesty, and unabashed self-love, but his craft as a writer is equally remarkable: “I’d let go of my country, my wealth, my class, my heterosexuality, and finally now my gender, until I was nothing but a body spinning in space.”

Brian Alessandro is a writer who’s based in Roselle Park, NJ.