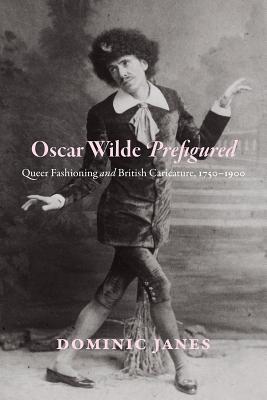

Oscar Wilde Prefigured: Queer Fashioning

Oscar Wilde Prefigured: Queer Fashioning

and British Caricature, 1750-1900

by Dominic Janes

Chicago. 279 pages, $40.

IN E. M. FORSTER’S novel Maurice, the title character confesses to his homosexuality by declaring that he is “an unspeakable of the Oscar Wilde sort.” In the late-Victorian and Edwardian imagination, which Forster’s novel evokes, Wilde’s imprisonment on charges of sodomy established him as the queer par excellence. Even before the trials of 1895, Wilde’s sexual deviancy was suspected. Indeed, his dandified persona had raised eyebrows as far back as 1881, when Gilbert and Sullivan satirized him as the limp-wristed æsthete Bunthorne in their operetta Patience. However, as Dominic Janes beautifully demonstrates, long before the Wilde brouhaha, homoerotic expression in the form of dandyism and æstheticism—“camping,” we might call it today—was conspicuous, and often accurately understood, in British society.

Janes, a professor of modern history at Keele University and the author of two previous books on queer cultural history, examines the history of male effeminacy as a marker of homosexuality. Wilde’s image—with its scandalous hints of sodomitical behavior—was prefigured, he argues, in the dashing 18th-century men known as “macaronis,” whose extravagant styles of dress exceeded the ordinary bounds of good taste.

Were the macaronis interested in same-sex sexual activity? Some were; others were not. In a world where “homosociality”—male-with-male clubbiness—was the norm, it’s not always easy for us, nor was it easy for the men of the 18th century, to tell who was cruising and who was just, well, putting on fancy outfits. Those who were looking for male-male sex, Janes explains, had to pull off an elaborate game: mimicking the appearance of sexual normality in public while simultaneously “queering” their heterosexual performances in order to signal to others in the know what they were really after.

This “oscillation between display and concealment, affirmation and circumspection” helped to create “a landscape of aristocratic effeminacy.” The manner, speech, and dress of æsthetes meant that “sexually subversive messages could be smuggled through.” It was, by and large, a game of hide and seek. One example is Sir Brooke Boothby (1743–1824), a translator and poet. “Like a puff of wind blowing this way and that, [Boothby] altered his social performance as he attempted to express his own identity and interests while also negotiating his place in relation to a polite society.” (A more contemporary example might be Liberace.) Janes scrupulously analyzes a portrait of Boothby painted by Joseph Wright of Derby (1781). While ostensibly a depiction of melancholy, Wright’s painting, through subtle irony bordering on kitsch, slyly depicts Boothby’s effeminacy and perverse desire.

Even more than serious portraiture, cartoons and caricatures of the period played a key role in the popular awareness of same-sex desire. They functioned, Janes writes, as conduits of gossip, attack, amusement, and celebrations of eccentricity. Caricature focused not only on the clothing of fashionable men, but also on body shape, deportment, and overall personal performance.

During the Regency era of the early 19th century, fashion-obsessed men called dandies also came under the scrutiny of caricature. Ostentatious male display—“dressy androgyny,” Janes calls it—was the new focus of suspicion and burlesque. Regency-era emphasis on the bodily similarity between men and women—impossibly tight waists, for example—continued to raise “sodomitical innuendo.” Janes devotes an intriguing chapter to the careers of the Cruikshank family, whose vehemently mocking images of the dandies suggest both fascination and disgust. While hardly a major step forward in sexual liberation, such mockery did at least begin to acknowledge the possibilities of queer self-presentation.

By the end of the 19th century, during Wilde’s heyday, a great number of effeminate young men had flagrantly taken to “peacocking about.” While all this strutting continued to borrow from the kinds of closet games practiced by sodomites of previous generations, there was now an even greater recognition of the erotic import of such behavior. But the Wilde generation, Janes emphasizes again and again, was the culmination, not the beginning, of this long tradition of queer male display.

In researching this fascinating book, Janes has certainly done his homework. He has uncovered, and convincingly explicated, a vast array of British cartoons and caricatures from the two centuries he surveys. He also seems to have read and mastered all the available scholarship on the queer history of this era. It’s an impressive performance, and one that largely, though not entirely, eschews the thick impasto of post-modernist jargon that often belabors similar studies.

Almost thirty years ago, Neil Bartlett, in his book Who Was That Man?, set out to appreciate Oscar Wilde’s London “as the beginning of my own story.” Dominic Janes has extended that project. He shows us that the history of queer performance—and its depiction in caricatures—“contributed both positive and negative elements to the images that became stereotypical of sodomites and thence, in the twentieth century [of]gay men.”

Many gay men today may cringe at the ultra-refined tradition of camp performance that the macaronis, dandies, and æsthetes of earlier generations adopted, but those men have left us with “repositories of queer knowledge” that still function as a “framework of positive self-expression.” In Dominic Janes’ book, we have met the macaroni, and he is us.

Philip Gambone is the author of Travels in a Gay Nation and several other books.