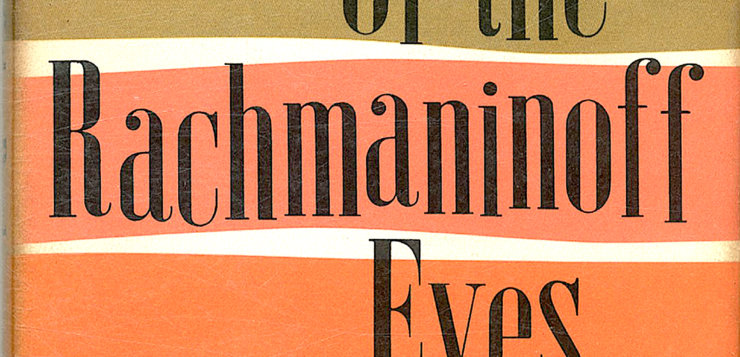

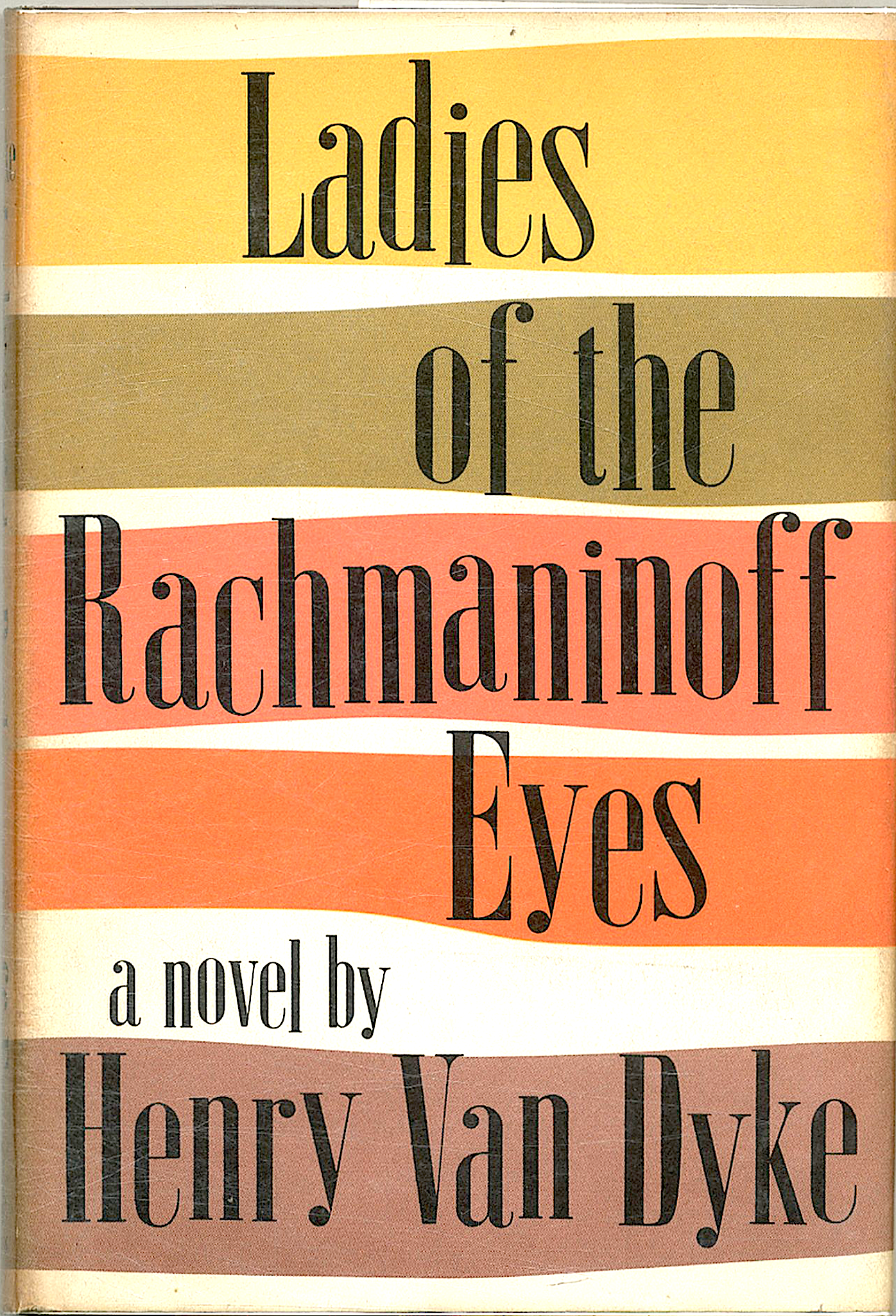

I FIRST BECAME AWARE of Henry Van Dyke’s 1965 novel Ladies of the Rachmaninoff Eyes, which was reprinted for the first time last year, when I read on the website Literary Hub the Foreword to it by Van Dyke’s nephew, Erik Wood. My immediate response was to ask: How is it possible that I, an English professor with an interest, both personal and professional, in gay literature, had never heard of this brilliant novel, or its Black and gay author? From Wood’s foreword I learned that Van Dyke began the novel in the late 1950s, but it took him several years to find a publisher. Reviews were favorable. The Kansas City Star proclaimed that Van Dyke “gives us cause to hope that the Burroughses, Rechys, and Mailers may at last be succeeded by writers as intent upon the elegant phrasing of their messages as upon the messages themselves.” The New York Times called Van Duke “a talented writer and a brave one.” The Kirkus Review proclaimed Van Dyke “a real talent,” comparing him to Shirley Jackson. James Purdy proclaimed that “Mr. Van Dyke is a rarity, for he has written a charming and incisive, witty and entertaining book. He has loads of talent.” Not unexpectedly, perhaps, I found no contemporary reviews that explicitly addressed the novel’s homosexual content, or identified Oliver, the narrator-protagonist, or Van Dyke himself as gay.

And then the novel and its author virtually disappeared. Neither Van Dyke nor his novel appears in the index of any of the critical studies of gay fiction on my shelf. But why? The most obvious reason is that the novel’s muted gay sensibility is distinctly pre-Stonewall and closer to the novels of Ronald Firbank and the plays of Noël Coward. (Oliver’s omnivorous reading includes Firbank). In other words, the novel was not nearly gay enough for most readers only a decade after it was published. “If you were a young Black writer in America in the 1950s and early ’60s,” writes Wood, “it was generally expected that you would write about struggle. It could be the struggle to put food on the table, or the struggle to walk down the street, or the struggle to maintain your dignity in a world that wanted to degrade you; but one way or another … struggle was almost a mandatory theme.”

And then the novel and its author virtually disappeared. Neither Van Dyke nor his novel appears in the index of any of the critical studies of gay fiction on my shelf. But why? The most obvious reason is that the novel’s muted gay sensibility is distinctly pre-Stonewall and closer to the novels of Ronald Firbank and the plays of Noël Coward. (Oliver’s omnivorous reading includes Firbank). In other words, the novel was not nearly gay enough for most readers only a decade after it was published. “If you were a young Black writer in America in the 1950s and early ’60s,” writes Wood, “it was generally expected that you would write about struggle. It could be the struggle to put food on the table, or the struggle to walk down the street, or the struggle to maintain your dignity in a world that wanted to degrade you; but one way or another … struggle was almost a mandatory theme.”

Van Dyke was certainly aware of political struggle. Rosa Parks was a friend of the Van Dyke family, and Martin Luther King, Jr., officiated at the wedding of Van Dyke’s sister. He closely followed the 1955–56 Montgomery, Alabama, bus boycott through letters from his mother, who baked corn muffins for the riders. Ladies of the Rachmaninoff Eyes, which the New York Times reviewer called a “light-decadent … confection,” seems, at least a first glance, as far from Black politics as Montgomery is from Allegan, Michigan, where the story is set and where Van Dyke was born.

The novel is a portrait of the artist as a young gay Black man, Oliver, who recalls his bizarre adolescence growing up in rural Michigan. Oliver, sexually innocent but intellectually and artistically precocious, is raised by his Aunt Harriet, housekeeper to the wealthy Jewish widow Etta Klein. The two women’s turbulent, codependent relationship is comically played out against the racial inequality of America in the 1950s. The novel’s cast of eccentric characters includes Etta’s Black cook Della Mae, who lusts after the young Oliver and plans to move to Chicago to become a prostitute. Into this strange ménage comes Maurice LeFleur, a self-proclaimed “warlock” who persuades Etta that he can contact her idealized dead son Sargeant, who mysteriously committed suicide in New York five years earlier. Etta has “adopted” Oliver as a replacement for her beloved son and is planning to send him to Cornell University. The climax of the story comes when Aunt Harriet reveals the scandalous family secret: Sargent was a closeted homosexual who left Allegan for New York, where he fell in love with a Black man. Aunt Harriet dies of heart failure trying to kill LaFleur.

This is not a story that’s likely to appeal to readers whose expectations of a “gay novel” have been formed by the works of post-Stonewall writers. Ladies of the Rachmaninoff Eyes is unlikely to raise the consciousness of today’s gay men by offering them a representations of gay lives they can identify with. Although Oliver’s only struggle in the novel is to resist the sexual predations of the lascivious Della Mae, Van Dyke is still able to subtly explore the issues of race and homosexuality at a time when such topics were rarely represented in fiction. And this, I would argue, is the basis of the novel’s artistic success. What’s most relevant for today’s readers is its portrayal of the relationship between Blackness and queerness in the novel’s young and sexually confused protagonist. The novel subtly reveals the similarities between the situation of closeted homosexuals and Blacks in 1950s America. But while race is foregrounded, Oliver’s gayness is only implied.

Although there are no direct references to the Civil Rights Movement, we learn that the Kleins’ Black chauffer, who “worked like a slave,” could have “passed for white any day,” and he comically does on one occasion, winning a bet that he could be served in a whites-only restaurant. Similarly, Oliver “passes” for straight. He resists the farcical sexual predations of Della Mae, who tells him: “Old Etta Klein’s trying to make a white boy out of you.” To which Oliver replies: “Really, Della, you certainly have a warped idea of what white boys are like. Just because I don’t—.” The reader is expected to fill in the blank. Even in 1965, a savvy gay reader could recognize that “white” was being used as a surrogate for homosexual.

Oliver even makes an awkward sexual overture to an older white woman with whom Sargeant’s younger brother is having an affair. “I’ve never bestowed any favors on a colored man—boy before,” she tells Oliver, while insisting: “It’s not that I’m prejudiced or anything, God knows, I’m really not.” Reflecting on the incident, Oliver says: “Della, raucous Della, had always proclaimed me white, and though I knew better, I never thought of being any color.” Neither does he think of “being homosexual,” but he must know better: he reads Les Fleurs du Mal while working on his poem “Decipherments & Discontinuities,” a title that hints at his efforts to figure out who he is. Early in the novel, Della Mae tells Oliver: “You don’t know a thing about living, kid, and you never will at the rate you’re going. … You’re so dumb about life it hurts.”

The relationship between the Jewish Etta and her Black housekeeper, while not sexual, certainly resembles a same-sex marriage. “They had woven a bickering, bantering tapestry together that was stronger than husband and wife,” says Oliver, “and it was not to be made light of; it was a high seriousness, their arguing; it was the way they made love.” Their conflicted co-dependence parallels the sadomasochistic relationship between Sargeant and his Black lover. Race and sex are mirrored in the relationship between Etta and Harriet and that between Sargeant and his Black lover. Sargeant commits suicide and Harriet dies of heart failure attempting to murder LeFleur. Beneath the comedy and farce lies tragedy. The novel concludes with Oliver leaving rural Michigan for Ithaca and Cornell, where he will enter the next phase of his journey of self-discovery.

Nils Clausson is emeritus professor of English at the Univ. of Regina in Manitoba, Canada.