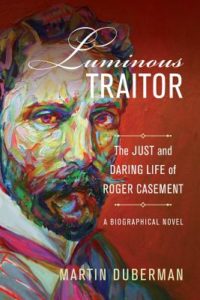

Luminous Traitor: The Just and

Luminous Traitor: The Just and

Daring Life of Roger Casement

by Martin Duberman

U. of California. 288 pages, $32.95

ROGER CASEMENT (1864–1916) was an Irish diplomat at a time when Ireland was part of Great Britain. He was among the first people to expose the humanitarian abuses in the Belgian Congo under the rule of King Leopold of Belgium. (Joseph Conrad also did so in 1899’s Heart of Darkness; he and Casement were actually roommates for a time.) Casement was also a secret homosexual, and he kept diaries detailing his sexual encounters with the native populace of the Congo.

Luminous Traitor is Martin Duberman’s attempt to shed light on an episode that is largely forgotten today, especially in the U.S. As a chronicler of the gay movement in such books as Stonewall (1994) and Cures: A Gay Man’s Odyssey(1991). In Hidden from History: Reclaiming the Gay and Lesbian Past(1989), he sought to excavate a gay and lesbian historical record that had often been lost, if not systematically erased.

Casement, keenly aware of the rights of the oppressed at the hands of an imperialist power by virtue of being an Irishman, was charged with investigating conditions in the Belgian Congo via his post in the British Foreign Service. He was appalled by the abuses he witnessed and wrote numerous reports detailing the atrocities. These reports, in turn, became a hot potato for Britain, which was uncertain how to respond on a diplomatic level. Rebuffed in his efforts to make the situation in the Congo better known, Casement was reassigned to several South American posts. During this period, while investigating the rubber trade in an area on the border between Colombia and Peru known as the Putamayo, he discovered a situation that was smaller in scale but actually worse the Congo. There, at the hands of ruthless, imperialist exploiters, thousands of the indigenous population were systematically enslaved, starved, raped, tortured, and killed. Indeed, Casement wrote: “The only real question remaining is which will be exhausted first, the Indians or the rubber trees. … I do not think the Indians will outlive the trees.”

Roused to outrage and indignation once more, Casement issued scathing reports. But again there was little action, as Britain asserted that it had no authority in Peru outside of a few workers at a British-owned company. Frustrated at being perennially sidelined in his efforts to draw world attention to two horrific situations, Casement threatened to retire, and—much to his shock and chagrin—his offer was accepted. He should probably not have been so surprised: Britain was more than ready to say goodbye to someone who was constantly presenting its leaders with difficult predicaments. Feeling betrayed and uncertain of his next steps, Casement visited the Gaelic-speaking islands off Connemara and was appalled by the poverty there. Indeed, he called the area an “Irish Putamayo.” The conditions were not unique to that area. At the time (1911–12) nearly a third of the population of Dublin lived in slums, and the mortality rate rivaled that of Calcutta. The trip seems to have crystallized for Casement a new resolve and direction. Always an outsider by virtue of being Irish, nonreligious, and gay, and always a defender of the oppressed, he wrote to a friend: “What loyalty can any Irishman with brains and heart have to any English government? I have none.”

Casement then made a fatal move that branded him a hero to some and a traitor to others. As World War I broke out, he saw England’s difficulties as an opening for Irish independence, and he met with officials from Germany in an attempt to align Ireland with Germany against England. The scheme went horribly awry for Casement, who was caught and imprisoned, though it provided the spark for the Easter Uprising of 1916.

During his trial, Casement claimed—naïvely or bravely, depending upon your viewpoint—that he was Irish, not English, and thus could not be guilty of treason. While there was initially a great deal of support for clemency due to his efforts in the Congo and Peru (George Bernard Shaw, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, and a great many others came to his defense), public sentiment quickly faded when excepts from his diaries detailing his many sexual encounters were published. He was subsequently found guilty of treason and hanged.

The broad outlines of Luminous Traitor suggest an Oscar Wilde-like story of wrongful prosecution and destruction of a uniquely talented individual at the hands of a homophobic public, and there’s little doubt that the details of Casement’s sexual escapades sealed his fate. But setting aside Casement’s sexuality, his decision to side with Germany over England during a time of war caused even some of his closest friends to abandon him.

Readers may be divided over Duberman’s decision to dramatize certain sections of the text in the absence of actual documents (he calls the book a “biographical novel”). He is adept at writing dialog, but sometimes the dramatized sections seem awkward, and often it’s unclear whether the dialogue is authentic or invented. Duberman states in an afterword that “Except in the dialogue sections, all material placed within quotation marks comes from primary sources,” but this doesn’t entirely clear up the matter. Ultimately, one wonders whether it might have been wiser for the author to have gone with all fact or all fiction.

Casement’s gay psyche is not explored in depth. For example, one wonders if he ever struggled with the possibility that he too was exploiting the people under subjugation by having sex with them. Does the fact that he was usually the receptive partner during sex (and seemed to like it rough) indicate that he was seeking punishment for his or others’ wrongdoing? He seems to have been an admirable human being, unduly wronged, perhaps because of his sexuality. Duberman’s presentation of his life story is impressive, but one leaves with a feeling that this will not be the last word on Roger Casement.

Dale Boyer is the author of The Dandelion Cloud, Thornton Stories, and the forthcomingJustin and the Magic Stone.