The Temple of Perfection: A History of the Gym

The Temple of Perfection: A History of the Gym

by Eric Chaline

Reaktion Books. 272 pages, $30.

IN HIS NEW HISTORY of the gymnasium, Eric Chaline writes that one reason people go to gyms as adults is that they enjoyed physical activity when they were young, though I’ve always suspected that for gay male gym-goers the reverse is often the case. This reviewer, at least, hated group sports growing up—they were something “real” boys did. Even in college, I was shy about using the gym; and it wasn’t till my mid-twenties, when I got to New York City, that I joined the YMCA. I’m not sure why. But it seemed part of being gay, like going to dance clubs or the baths.

There was of course a direct connection between the gym and the baths for gay men; the latter was where you got rewarded for the work you did in the former. On the other hand, bathhouses like Man’s Country on 15th Street that included gyms never worked, for some reason, as if one had to either work out or have sex, and the two could not be combined. At the gym one was doing something beyond sex, something pure and idealistic: fashioning a body, disciplining a self. What had terrified me years before—lifting weights, working out—seemed to me alluringly masculine in a way it hadn’t when I was twelve. Like so many gay men who hated locker and shower rooms when they were in junior high, I ended up finding them quite stirring.

The West Side Y on 63rd Street was my first gym, followed by the McBurney Y on 23rd, and years later the National Capital YMCA on Rhode Island Avenue in Washington, D.C. The Y’s always made sense to me because they had so much besides weights: a running track, squash courts, a swimming pool. At the West Side Y I even learned gymnastics, largely because of what a man named Tony di Bellas looked like in his white tank top when he did the rings, his muscular arms dusted with chalk.

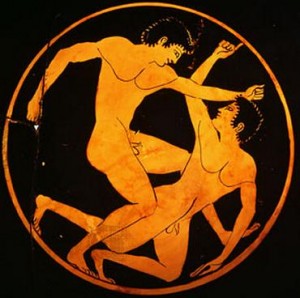

The gymnasium first appeared, in Chaline’s account, in ancient Greece, where it was a place at which one not only played sports but also heard lectures, found mentors, and learned to be a Greek citizen. Then Rome conquered Greece, and the gymnasium became the public baths. Then Christianity came along, with its low opinion of the body, and both versions vanished altogether until an Italian humanist wrote a book on exercise in the 16th century; though what really revived the gym was Napoleon’s defeat of the Prussians in 1806. The Prussians were so appalled by their defeat that they decided athletic training was necessary to raise the fighting mettle of their young men, which led them “to redefine exercise as a mass movement of national salvation.” Meanwhile, the Enlightenment had introduced the modern idea of happiness, which, along with the later invention of photography (which enabled people to see and record their own bodies), led to the desire to make one’s body as beautiful as one could—something like, but not quite the same as, the old Greek concept of arête, a word that means achieving one’s full mental and physical potential. And then came Eugene Sandow, a professional body-builder (a role that originated in circus troupes), who cut a large swath through 19th-century Europe with photographs of his beautiful physique, books about exercise, and even gyms. None of the latter lasted, though, until the golden age resumed in Southern California, at Muscle Beach, and American body builders like Jack LaLanne and Vic Tanny started the gym franchises that were the forerunners of the ones we have today.

All this is a rapid overview of Chaline’s meticulous effort to place the gymnasium in the history of Western man (with a brief glance at Asia). There were, as he sees it, four stages in the history of the gym—ancient Greece, Prussian Germany, mid-19th-century Paris, and the contemporary gym. In this sequence, the Greek idea of creating disciplined citizens gave way to the Prussian demand for healthy cannon fodder, and finally the more narcissistic goal of feeling good and making oneself attractive, at which point we modern gym-goers represent a variation on the Greek ideal, in which, Chaline writes, “for the convert minority”—only sixteen percent of Americans go to a gym—“the gym has once again become a quasi-religious space—a temple dedicated to personal identity and the perfectibility of the body, where members pursue and achieve their individual arête.”

Certainly in yoga class the parallels to a religious gathering are obvious, but everything Chaline says about the modern gym rings true, including the division between men and women—the former drawn to weight lifting, the latter to exercise classes. These days I find myself more and more doing group exercise in rooms of twenty-something women with pony tails while straight guys are downstairs lifting weights. Straight men, Chaline says, when threatened by feminism, resorted to body building in order to become hyper-males, distinguishing themselves from both women and gay men.

In a chapter on the gay gym, which Chaline views as part of gay liberation, we see how the ideal body underwent a change—from the hyper-masculine, super-weight-lifted bulk that Arnold Schwarzenegger, among others, popularized in gyms that resembled “dungeons” on the West Coast, to what Chaline terms “the fit body.” Of course, if people are no longer to exercise so they will make good soldiers, one has to ask: fit for what? Sex, I guess, would be the gay man’s answer—even if one continues going to gyms long after one has left the sexual marketplace, because working out has so many mental and physical benefits. Even when one was in the sexual marketplace, of course, working out guaranteed nothing. It was gay people who coined the phrase “Muscle Mary” to say that you can work out all you want, get as big as you please, but it still doesn’t mean you’re butch.

This reinterpretation of masculinity is one of the themes of The Temple of Perfection. Even the clothes that straight weight lifters use when working out reflect this phenomenon. Chaline points out that the baggy clothes straight weight-lifters now wear disguise the genitalia once revealed by the posing strap and brief bikini. Part of this is modesty and part of it insecurity, Chaline says, because our culture prizes big genitalia the way the Romans, though not the Greeks, did. The reason the Greeks valued small cocks is because small genitalia, as seen on their sculpted figures, stood for a man’s mastery of sexual desire, and mastery of the self was the chief goal of the Greek gymnasium. The Romans, on the other hand, not only turned the Greek gymnasium into the Baths of Caracalla, but celebrated those giant phalluses one sees on the satyrs holding up bowls and cups in the Museum of Antiquities in Naples. Americans, apparently, are more Roman than Greek.

When I joined the National Y, they had just experienced a crisis about sex in the steam room and sauna, and I was told that many gay men had moved to other gyms. The men’s shower was still one big open room with spigots along the wall and the occasional gay man standing in the stream of water with a full erection. But then partitions were put up, and then shower curtains on the cubicles, and then I began noticing young men I assumed were Muslim who would undress and dress at their lockers with towels wrapped around their loins, though they may not have been Muslims at all but rather young men who were aware that gay men might be looking at them. (The history of modesty could itself be the subject of a book). The way straight and gay men, and women, use the same space is itself part of the new gymnasium, something that, like gym culture itself, is always in flux.

The paradox of gyms is that they seem unaffected by recessions but are subject to shifting demographics and concepts of exercise. In Chaline’s view, the mid-size gym is threatened by smaller boutique gyms and the mega-monsters. It’s constantly evolving. There are now gyms that don’t require a year’s membership, classes that can be conducted outdoors, in city parks, and there are trends in exercise—Pilates, yoga, the ball, circuit training—that anyone who goes to a gym cannot help but notice. In the future, Chaline imagines, there may be gyms in jumbo jets.

Chaline’s book is full of interesting information, not to mention its useful historical overview, and it’s written in clear, sensible prose. But it can seem, at times, like a dutiful term paper. Even personal anecdotes from his own gym experience do not relieve the tone. Yet we learn a lot. We learn that, not only did the Greeks exercise and compete athletically in the nude, but that rich men were expected to donate the expensive olive oil with which athletes covered themselves, along with various powders to control body temperature, before they worked out; that they tied a narrow leather thong to the head of the penis to keep it in place—a thong that was compared to a dog’s leash, since the slang word for penis in ancient Greece meant “dog.” We learn that in the Greek gymnasium there was music played on flutes to accompany some exercise; that after a Greek athlete’s body was scraped with a curved metal device called a stlengis (the Roman strigil), the residue of olive oil, sweat, powder and defoliated skin was retained for therapeutic purposes (ick), though how he does not say; that Harvard opened a gym in 1826 but closed it not long afterwards, an idea before its time; and that gym owners believe that the closer you live to a gym, the more likely you are to use it (ten minutes away is ideal).

The National Y in Washington—which was only four minutes from my apartment—just announced that it’s closing and selling the property on which it stands to a developer, because the land has became so valuable and membership has shrunk due to competition from all the new gyms that have opened nearby. Perhaps that was one reason I went as much as I did, sometimes twice a day. But it wasn’t just that. It’s what Chaline says about the modern gym: the way it has become for its members a family and, yes, sometimes a religious experience. Sitting in yoga on Sunday mornings in the huge studio on the seventh floor, looking out over the rooftops with my fellow yogis, was to feel a wonderful sense of companionship and serenity. That’s why we’re all in shock. Not only that: the National Y was wonderfully integrated in terms of age and ethnicity. If I was often the only old guy in a sea of ponytails, it didn’t matter. The gym had become, as it has for many gym-goers, especially gay people, a big part of my emotional and social life. One forms bonds at the gym—even with the person who hands you the key to your locker. Where everyone will go now I do not know. On December 31st, it closes for good. Nor will it be moved elsewhere, like the Queen Mary to Long Beach. It will simply be smashed by the wrecking ball—and all that sweat, all that beauty, all that effort and high spirits, will become a memory.

It was a mistake, I see now, to think the National Capital YMCA was as permanent as a Mother Church; it was just another gym, subject to the changing tastes, demographics, and conceptions of exercise that Chaline’s book traces back to ancient Greece. People wanted something gayer, something newer, something closer to their gentrified neighborhoods—all preferences that seem to me now to have destroyed the best gym in the city. For there will never be a gym as big and light-filled, or a pool as beautiful, as the one at the National Capital YMCA. Which makes me feel like Norma Desmond in Sunset Boulevard. I want to say: it’s the gym-goers that got small. One good thing about reading Chaline’s book is that it helps one to put even this in context.

Andrew Holleran’s novels include Dancer from the Dance, Grief, and The Beauty of Men.