Shuggie Bain

Shuggie Bain

by Douglas Stuart

Grove Press. 448 pages, $17.

WINNER of the U.K.’s Booker Prize and a finalist for the National Book Award in America, Douglas Stuart’s Shuggie Bain is perhaps the bleakest great novel to appear in a long time. It is the bleakest, most shocking, and most harrowing account of a childhood I’ve ever read, and this includes anything by Dickens. At the end of thirteen pages, the fifteen-year-old Shuggie is already selling himself to men for money. Barely thirty pages later, he narrates the way his mother tried to set the house around them on fire with him in her arms. And there are still nearly 400 pages to go. Given all this horror, it may be appropriate to ask (and many have), how much is too much? That Shuggie Bain is a literary triumph is a testament to the author’s skill at keeping us from closing the book in despair.

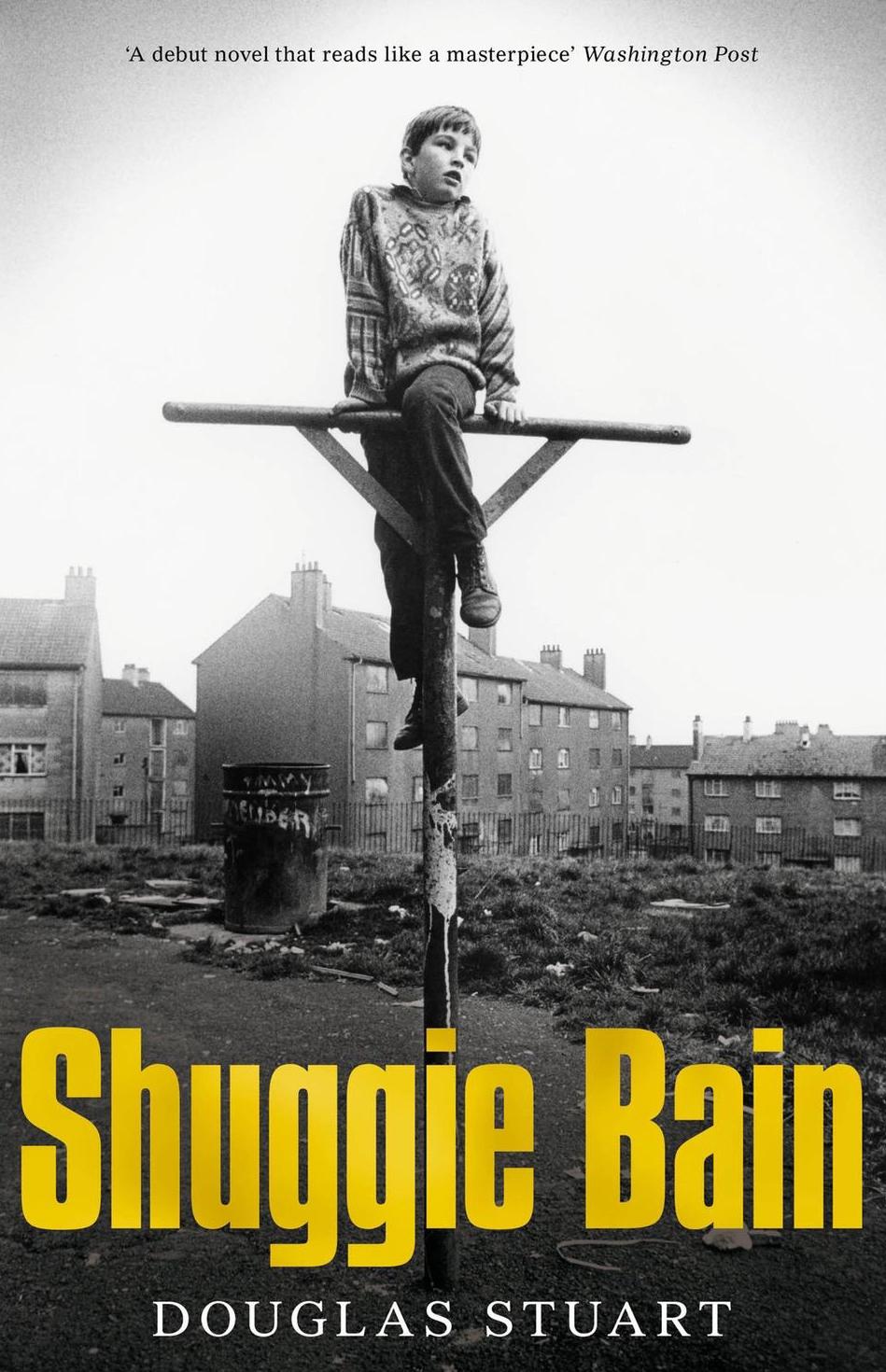

The British edition’s cover portrays a child almost literally crucified on a pole against a backdrop of Glasgow’s public housing, while the U.S. edition shows a child in bed, gazing adoringly at his mother. Both images are equally apt, summing up the novel quite neatly with its twin themes of adoration and destruction. The title is a bit misleading, because, while Shuggie is the book’s ten-year-old gay narrator, the novel is essentially a portrait of his alcoholic mother Agnes. Seen through Shuggie’s innocent and uncomprehending eyes, Agnes is a deeply unhappy woman, reminiscent of Martha in Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf, to whom she is actually compared. Agnes seems determined to live her life like a star, as in the moment when, after the fire she herself has caused, she moves out of her parents’ home in an attempt to start a brand new life: “Now, as the taxi pulled out into the main road, Agnes made a show of looking back and waving mournfully through the rear window with a long, heavy blink. She thought it was a cinematic touch, like she was the star of her own matinee.” Sadly, however, while Agnes spends her life mooning for some imagined camera, no one is watching.

Fueled by a series of bad choices with men, and perhaps her own unrealistic expectations about life, Agnes slides ever more irrevocably into hopelessness and despair, dragging everyone nearby down with her. If Shuggie Bain were a mere catalogue of such horrors, none of this would be bearable. But Stuart succeeds in making her, if not entirely sympathetic, at least understandable. He’s also successful in capturing the inner workings of several other characters, including the naïve, effeminate Shuggie and even Agnes’ no-’count, wife-beating husband, Shug Sr. He has mastered the art of establishing characters and scenes through dialogue, as in this exchange when Agnes meets her new neighbors in the down-and-out section of the Glasgow housing project where they now live:

Agnes lifted the vodka mug again and stared down into the faint clouds. The tea must have been very milky. Bridie topped it up to the brim with a smile. “Aye, ah took ye for a drinker.” She drew on her fag. “Aye, the minute ah saw ye, ah spotted it. They thought you were the big I Am, all done up in sequins, like some big dolly bird from the city. But ah could see through it. Ah could see the sadness, and ah knew you had to be a big drinker.” The women nodded and cawed “Aye,” like a murder of crows.

Trying to cope with life in these environs, and in the bleakest days of Thatcher-era Glasgow, is the young Shuggie. Gay and bullied by everyone except for his protective older brother, who does everything within his limited means to save him, Shuggie is witness to his mother’s inevitable decline, and he’s saddled with the additional burden of trying to forge a gay identity in this completely hostile environment. It is Shuggie who watches nightly as Agnes pulls can after can of Special Brew from its “plastic noose” (an especially apt metaphor), and it is he who endures the shocking bluntness and coarseness of their daily lives in down-and-out Glasgow. This is a world in which seemingly no doorway, elevator, or square of carpet is free from the taint of piss, in which every human interaction is reduced to its coarsest elements, and in which no one seems capable of breaking free from the cycle of poverty.

Yet, in the end, the book is about Shuggie, and the fact that he survives—indeed, triumphs over—all of this adversity. The author acknowledges in an afterword that the book is at least partly autobiographical, so Shuggie Bain is a testament to how great art can be made in the face of such suffering. Bleak and gritty as it may be, it is also a deeply human and unforgettable work of fiction.

Dale Boyer’s most recent book is Justin and the Magic Stone. His new poetry collection, Columbus in the New World, is forthcoming.