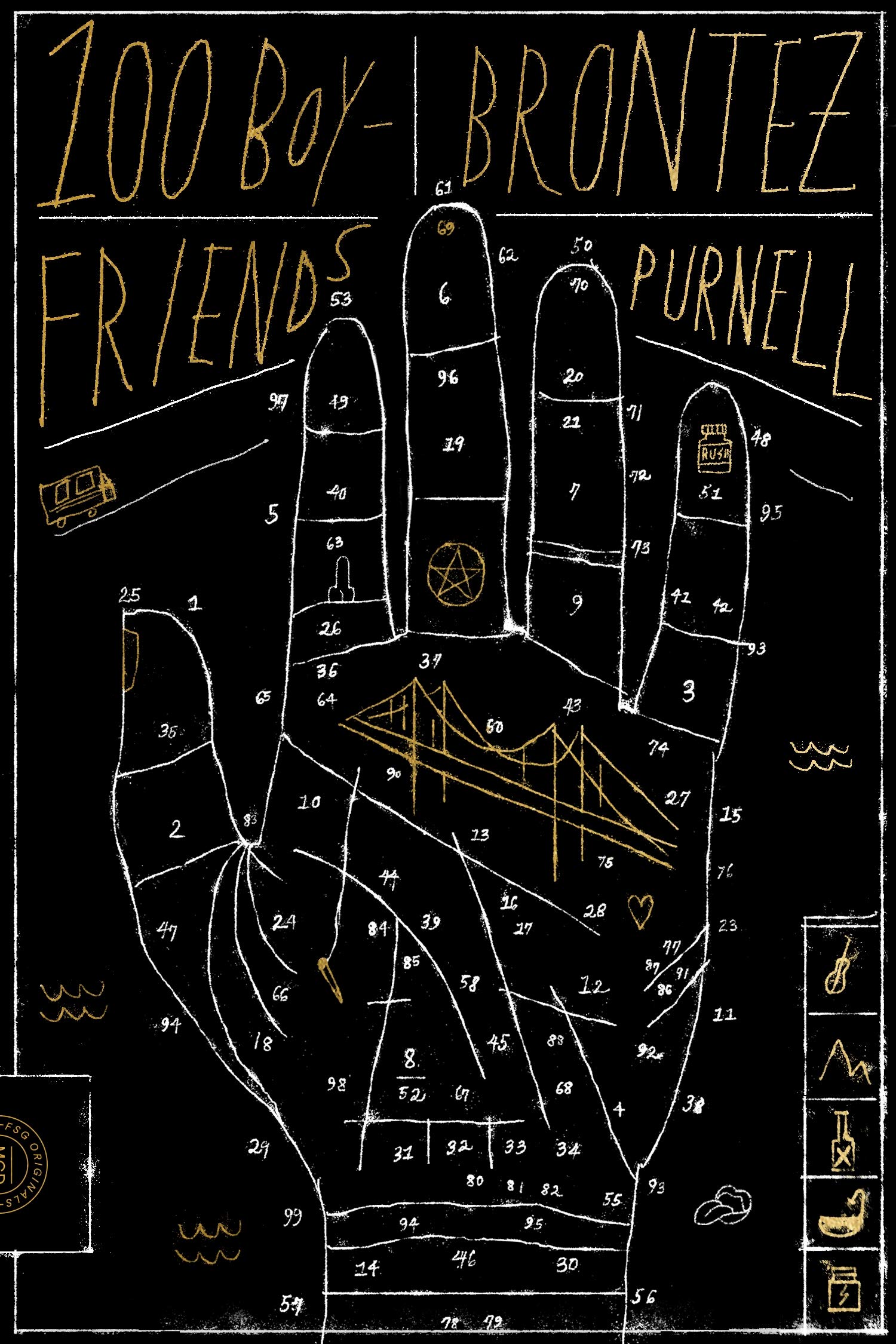

100 BOYFRIENDS

100 BOYFRIENDS

by Brontez Purnell

Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

180 pages, $15.

IN THE WORLD according to Brontez Purnell, guys throw down half a handle of whiskey before ten in the morning, can’t remember the last time they had fun having sex, and find the task of having to respond to stimuli to be “exhausting.” It’s a world of “jaded, judgmental borderline misanthropes” who end up fucking in “shit-scented public restrooms.” In the world according to Brontez Purnell, most guys are whores.

The narrator of these mostly first-person stories is an educated, slightly overweight Black man—an “uppity Black faggot”—with an affinity for, to put it delicately, undomesticated sex. More often than not, he just wants to “get fucked good.” Excess is one of the dominant themes here—too many drugs (cocaine, THC, Percocet, benzos, acid, Xanax, “speed-laced bullshit from little baggies”) chased down with “limitless fountains of vodka” and gallons of antibiotics. “Sober fun,” the narrator says, “was damn near an oxymoron.”

100 Boyfriends is the fourth book by Purnell, who is also a musician, dancer, filmmaker, and performance artist. Indeed, the book is as much a loud, hard-core performance piece as it is a collection of stories: part rant, part stand-up comic routine, part gross-out shtick, part bravura Gen-X aria.

Purnell, a 2018 recipient of the Whiting Award for Fiction, was named one of the 32 Black Male Writers of Our Time by The New York Times Magazine. And, yes, he can write! He is a master of a variety of prose registers: sassy, lyrical, angry, raunchy, tender. And uproariously funny. Of one sexual encounter, he writes: “I had never witnessed a person’s fake orgasm taking so much out of them.” About another hookup with a self-absorbed guy, he asks: “Must I always have to bear witness to his soliloquy of love for dick?” About a third, Boyfriend #77, he says: “Sooner rather than later I was knocking back shots of him like a fucking prizefighter.”

One of the many delights of 100 Boyfriends is Purnell’s ability to capture a character in a single sentence: “The man hadn’t changed his make-out music since the nineties—it was all Cibo Matto tapes and other artifacts from his old hipsterdom that he carried around like duffel bags.” In another story, he can’t imagine how his sex partner would get a dick in his mouth: “he talks too fucking much.” Of another, he writes: “He was the only man I knew whose sex was that fluid: boy, girl, everyone in between, whichever race, that boy was sticking his dick in everybody and I admired the caliber of slut he was.” Slutty sex gets plenty of airtime here: “I had fucked enough boys with Catholic damage to know that if he’s wearing a crucifix, he’s definitely a ho.”

Purnell has a talent for rolling exuberance, jaded braggadocio, and bawdy hilarity all into one knock-out punch of a sentence: “We had fucked each other so much that sex at times felt like we were scraping the last bit of toothpaste out of a tube that shot its last load two paychecks ago.” In this pinball machine of a book, there’s hardly a sentence that doesn’t ricochet, bounce, careen, and slam its way right to the mark.

While Purnell has described himself as a cross between Tyler Perry and Tennessee Williams, the writer who came to my mind as I read 100 Boyfriends was Arthur Rimbaud, the bad-boy teenage French poet of the 19th century. Like Rimbaud, Purnell can sometimes be unabashedly, unapologetically romantic—in a hipster, bad-ass kind of way. One of the longest stories in the book (and one of the few written in third person) is the poignantly lyrical “Ed’s Name Written in Pencil” about an elementary school crush.

It’s hard not to wonder how much of 100 Boyfriends is autobiographical. “I mix fiction in here and there to protect the innocent, as well as the wicked,” Purnell told Frank J. Miles in a Lambda Literary interview in 2012. “What’s funny is the stuff that’s fiction is always taken to heart and the very true things people interpret as fiction from time to time.” Whatever the case, I’m guessing that every gay man will meet at least one of his own former boyfriends, or hook-ups, in these shameless, funny, sad, and blatant pages.

Purnell has described his technique as “very southern gothic style and very, forgive me for saying this, niggerish.” His experience as a gay Black man in 21st-century America is at the book’s core. In one story, a white boy who had been cruising a guy who works at a diner tells him: “I don’t think I had ever seen anything like you before.” Years later, the narrator wonders: “Anything like me how? Did he mean a punk boy who worked at a diner? Or did he mean a Black boy like me? Or did he mean something outside the Venn diagram of sociopolitical identity politics?” Black pain, frustration, loneliness, anger, and rage often percolate just beneath Purnell’s humor.

Toward the end of the book, Boyfriend #100, a literary agent, questions the narrator about his new poems: “What’s the journey?” he asks. “I don’t care for a journey,” the writer explains. “I’m just making a map, something that says, ‘You are HERE.’” In the world according to Brontez Purnell, right here, right now is often the whole point. It is a world where pasting a label onto experience, shoehorning the things that you do into hackneyed categories, misses the point. Whether there is something blissfully liberating or totally fucked-up about that refusal is for each reader to decide.

Philip Gambone, a frequent contributor to these pages, is the author of the recently published As Far As I Can Tell: Finding My Father in World War II (Rattling Good Yarns Press).