AS I APPROACHED the precipice, there were no maps for coming out of the closet. I knew I was gay from childhood, but had made up my mind that I would never act on it. I didn’t for years.

When I was fifteen and entering a new school in South Orange, NJ, a boy named Scott B, who was out with pride as well as being aggressive and obnoxious, pressured me to come out. That scared me into deeper denial. Then, during my first week of college in 1977, a young man who had been two years ahead of me in high school named Eddie L put even more pressure on me to come out. Now free and open himself, he pushed me to be ready. I wasn’t. In September of my sophomore year, I met a Carolina boy with ethereal vocal cords, and I fell in love. Not wanting to be the one to see me through the highs and lows of self-discovery, he walked away, leaving me heartbroken and alone to navigate the journey without him.

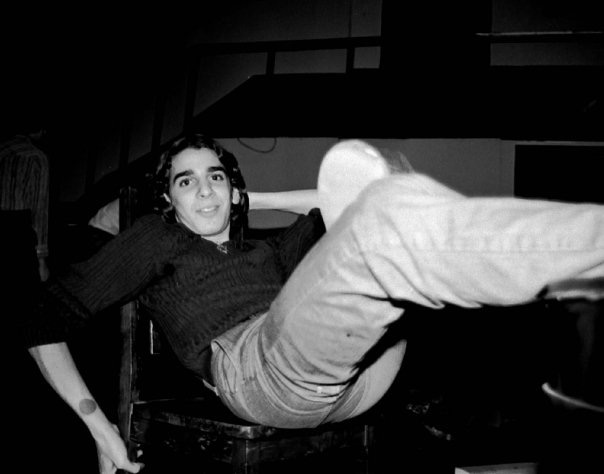

Everybody takes an uncharted and personal path to find and become who they are. I flew out of the closet but didn’t act on it sexually for nearly six months. I was waiting to fall in love. Looking back, I miss that naïve side to me. I went to all the gay bars and clubs throughout New York City, but didn’t give in to sexual impulses until just before my twentieth birthday.

I had moved into a loft-style apartment on Thompson Street in Manhattan, complete with roaches and yellow shag carpeting, with my college friend Cathy. On the night of our housewarming party, a man with black eyelashes and green eyes who lived across the hall showed up. According to Cathy—though I don’t remember this at all—I told her that I was going to have sex with him. I went back to his apartment, went down on him, and then threw up in his bathroom. Not because of the oral sex, but because I had drunk one too many black Russian cocktails.

I was fortunate to have had close friends growing up. When I came out of the closet, I forfeited some of them. I couldn’t face them, knowing I had lied. I didn’t understand that piece of the puzzle for decades. It wasn’t just cowardice, as I professed. I had told deep, personal secrets to certain friends but never admitted my attraction to men. When I came out, though, no one in my life was surprised to learn that I was gay.

Years later, when explaining I had been a teenage liar, sympathetic ears dismissed it, but I wasn’t looking for excuses. It’s not for others to accept or deny. I may have lied with sincere reason and without malice. Still, by omission, I had lied.

I had no gay role models growing up—not in life or literature, on TV or in movies, so I didn’t know what I was supposed to do. I’m impressed by and somewhat envious of the younger generation. They don’t ache over or necessarily define themselves by who they sleep with. (I realize I’m making generalizations.) I still see myself as being gay first and a man second. It took me years to know I’m okay.

During one of those “What if?” games that I was playing with drunken friends not too long ago, the question asked was: “In your next life, what kind of person would you want to be?” I answered without pause: “A gay man.”

Although it took a while, I shared an enviable relationship with my parents. I have time-sustained friendships and a relatively happy day-to-day life. A good many friends my age, both straight and gay, men and women, now find themselves single. While I’m sorry I don’t have a partner, I recognize that I don’t do the lover thing very well. I’m not lonely or needy, those stony barriers to finding companionship as we get older. When I was young, beyond wanting a lifelong lover, I also judged single persons to be “less than” those with a partner. Perhaps that’s a human trait—the coupling, not the judgment. We aren’t meant to be alone. But to that point, I repeat, I’m not lonely.

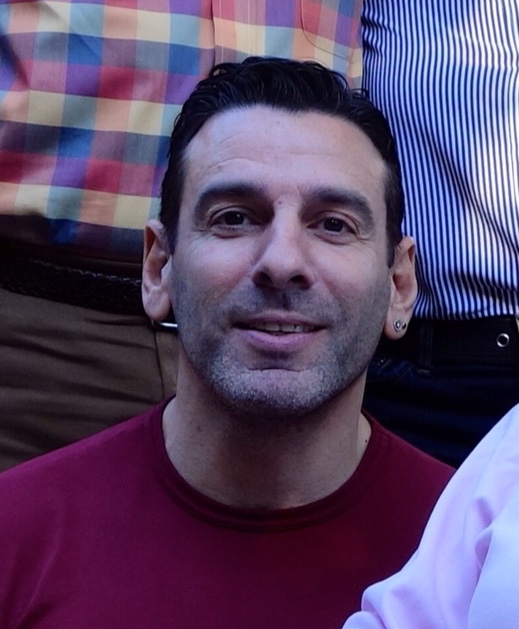

At my sixtieth birthday celebration, I was surrounded by people who love me. I thought, “How lucky am I?” I went home to my books and music, paintings and photographs, and stared at the collection of keepsakes that I’ve hoarded throughout my lifetime, each representing stories I’ve cherished through the years. As tough as my life has sometimes been, there are many more smiles than tears.

Andrew Sarewitz has written several short stories, scripts for various media, and more than 100 musical compositions. His play, Madame Andrèe, won First Prize from Stage to Screen New Playwrights series, as well as receiving an Honorable Mention from both the 2018 Writers Digest Competition and the 2018 New Works of Merit Contest. The script for his play Five Men, Four Beds advanced to the Second Round at the 2019 Austin Film Festival Competition and Andrew’s spec script for his sitcom, The White House, was a Finalist in the 2019 Pitch Now Screenplay Competition. Andrew has also authored numerous historical and critical artist essays with a primary focus on twentieth century non-conformist art from the former Soviet Union. Learn more about Andrew at: www.andrewsarewitz.com

Andrew Sarewitz has written several short stories, scripts for various media, and more than 100 musical compositions. His play, Madame Andrèe, won First Prize from Stage to Screen New Playwrights series, as well as receiving an Honorable Mention from both the 2018 Writers Digest Competition and the 2018 New Works of Merit Contest. The script for his play Five Men, Four Beds advanced to the Second Round at the 2019 Austin Film Festival Competition and Andrew’s spec script for his sitcom, The White House, was a Finalist in the 2019 Pitch Now Screenplay Competition. Andrew has also authored numerous historical and critical artist essays with a primary focus on twentieth century non-conformist art from the former Soviet Union. Learn more about Andrew at: www.andrewsarewitz.com

Discussion1 Comment

Once again the truths of your story touch me on such a personal level. I am not gay but I am a 62 year old single woman who isn’t lonely although many people think, and some even say, you need to have a husband…my response to them is very simple..been there done that…lol! You are exceptionally talented. Never stop writing Drew!