On July 12, 1979 disco was assassinated by the American people. Just two years earlier, Jimmy Carter became the first president to playdisco in the White House, and films like Saturday Night Fever (1977) and Thank God It’s Friday (1978) demonstrated the mainstream popularity and appeal of the genre. Artists like Donna Summer, the Bee Gees and ABBA consistently topped the charts and dominated the airwaves of the late seventies. A counteraction to rock music’s dominance, disco became an important component of the counterculture movement sweeping the United States, rebelling against the mainstream, repressive culture. Within the nightclubs of America’s major cities, discos were an opportunity for individual expression. In these crowded dark-rooms, people could truly embrace themselves. The conservative exterior world was shut out and self-expression, without fear of repercussion, could take place between these walls, a rare opportunity for many of the Black and Queer artists who laid the groundwork for the music. The Civil Rights movement was still a comparatively recent memory, and it took until 1973 for the American Psychiatric Unit to declassify homosexuality as a mental illness. It would take until 2003 for same-sex relationships to be legalized across the US, following the Lawrence v. Texas case. Disco’s inherent relationship with queerness, with sexual liberation and women’s empowerment movements, caused tensions with mainstream America. By February 1979, disco albums swept the Grammys, and like it or not, the music was firmly in the public eye.

By the early 1970s, the optimism of the hippie movement was fading away. The struggles of Vietnam, the assassinations of Dr. Martin Luther King and John F. Kennedy, the Watergate Scandal, and rising crime across American cities, most notably New York’s transformation into ‘Fear City,’ contributed to this. Nightclub music offered a form of escapism. Richard Dyer’s seminal essay ‘In Defence of Disco’ elaborates: “Given that everyday banality, work, domesticity, ordinary sexism and racism, are rooted in the structures of class and gender of this society, the flight from that banality can be seen as a flight from capitalism and patriarchy themselves.”

Prior to the emergence of disco, due to the homophobic laws that prohibited same-sex dancing, most gay bars were underground dance bars; many of their attendees took bail money with them on nights out. These bars were frequently raided by the police, most famously leading to the 1969 Stonewall Riots. Following the socio-political shift post-Stonewall riots, same-sex dancing was legalized. Despite this, many clubs still enforced their own policies, forcing the LGBTQ community and allies to create their own spaces. Rather than live bands, these ‘proto-clubs’ would play music off vinyl records, or disks. David Mancouso began organizing his own private non-profit ‘dance parties,’ in The Loft. Because these were legal, they could not be shut down by police raids, and attracted a diverse clientele. Alex Rosner, the Loft’s sound engineer elaborates: “It was probably about sixty percent black and seventy percent gay…There was a mix of sexual orientation, there was a mix of races, mix of economic groups. A real mix, where the common denominator was music.”

Seeing the success of The Loft, other clubs opened: The Church, The Gallery and The Pavillion, to name a few. Despite their differences, all played music which allowed the club-goers, often from the most marginalized groups of society, to lose themselves in the groove. These underground clubs relied on their DJs, curating music through innovative methods of mixing and sampling. Much of this was drawn from Progressive Soul, with artists like Isaac Hayes and Curtis Mayfield. Disco pulled from Latin American music, reflecting the background of many of the early disco-goers. By playing records and sampling musicians, clubs were affordable, unlike the expensive rock shows of concurrent acts like Led Zeppelin or Pink Floyd. Due to this, disco offered an affordable form of entertainment and exploded up the charts in the mid-1970s, bringing white and heterosexual communities into the disco sphere. This demonstration of the mainstream success of disco is perhaps best shown by the infamous Studio 54. The opulent hedonism of this club, famous bacchanalia-like parties, attracted celebrities as diverse as Andy Warhol and Michael Jackson. And yet, despite this mainstream appeal, even Studio 54 was carried by the queer community. A gay man called Marc Benecke led the security team, who while trying to keep true to the roots of disco, often turned away straight men.

Much of disco music’s message was one of empowerment, particularly for women and the queer community, particularly Black and Brown queer communities. Songs like Diana Ross “I’m Coming Out” (1980) or Sylvester’s “You Make Me Feel (Mighty Real)” (1978) focused on how disco had allowed them to achieve feelings of belonging and freedom. Chaka Khan “I’m Every Woman” (1978) embraced the idea of Black feminine unity and sisterhood, as Sister Sledge’s “We Are Family” promoted the idea of community. Sexuality was also embraced, The Village People’s “Macho Man” (1978) holds a strong homoerotic subtext, and ABBA’s “Gimme! Gimme! Gimme! (A Man after Midnight)” (1979) celebrates female agency in sexual relationships. Most interesting perhaps was Andrea True’s “More More More” (1976), herself an adult actress at the time of recording, singing about the filming of pornographic content. And the music itself meant something different than rock.

However, once disco became mainstream, it ran the risk of losing many of the queer elements that had been so important to the start of the movement. Saturday Night Fever was a result of both the culmination and death toll of disco. The film was a resounding success and the writer Nik Cohn explained the evolution of disco as, “the [disco]craze had started in black gay clubs, then progressed to straight blacks and gay whites and from there to mass consumption—Latinos in the Bronx, West Indians on Staten Island, and, yes, Italians in Brooklyn.”

The success of Saturday Night Fever led to its music and storyline being replicated in many imitation films. However, the soundtrack was dominated by the Bee Gees, and this, combined with the heteronormative story and lack of queer representation, was not representative of the diverse and queer origins of the music. As disco came into the mainstream, it was contrasted with rock, the former being seen as representing an effete diverse urban population, the latter a conservative blue-collar rural population. Bands like Lynyrd Skynyrd, The Allman Brothers, and Van Halen, were more popular in these areas, their music guitar-centric and often written through the male gaze. Within the cities bands like the Ramones were starting Punk music, a reaction to dsco music and the perceived overindulgence of the style. By stripping music to the barest bones, putting an emphasis on DIY ethics, it was as far removed from the exclusive studios required for disco. Disco was the most popular music in the United States, and had spread to the rest of the world, but this was not without a backlash. Peter Braunstein explains how, “The rise of disco had brought with it the mainstreaming of gay, possibly the opening salvo in the queering of America. Yet it wasn’t homosexuality per se that disco ushered in but a sustained exploration of the sexual self, including the femme side of the male persona (…) Needless to say, this world turned upside down made another, discophobic America very nervous.”

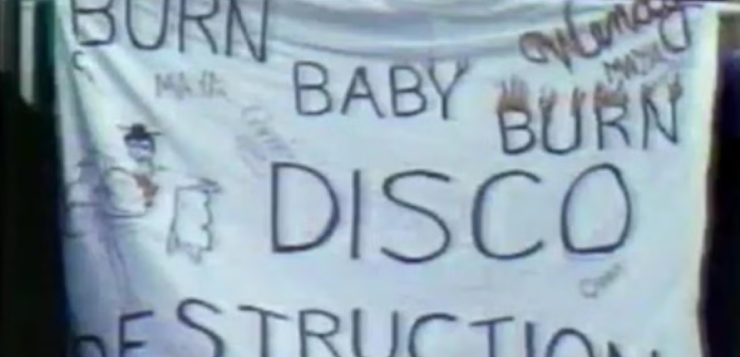

‘Disco Sucks’ became a by-word of the fans of rock and punk, one whose homophobic connotations were far stronger in the 70s. As disco grew and grew, bands like Pink Floyd and The Rolling Stones released their own disco records, the backlash against the genre increased. A group of DJs in Detroit, calling themselves the Disco Dux Klan, protested against the music by refusing to play disco music, another in Oregon destroyed a disco collection with a chainsaw. In Seattle, rock fans overtook a mobile dance floor. This response often had racist and homophobic undertones.

On July 12, 1979, the Chicago White Sox hosted the Detroit Tigers. To promote the game, DJ Steve Dahl, who had been the most outspoken disco critic on US airwaves at the time, offered reduced prices to fans who brought a disco record in with them. These records would be blown up on the pitch at half-time. The White Sox averaged an attendance of around 15,000 fans a game, for this particular game, 50,000 people showed up. The records were collected, although Vince Lawrence, a black employee of the Sox, pointed out that many of the records were by Black rather than disco artists, and placed in a container rigged with explosives. They were blown up at the interval and the attendees rioted. As writer Craig Werner points out, “the attacks on disco gave respectable voice to the ugliest kinds of unacknowledged racism, sexism and homophobia.”

After this, disco was somewhat replaced by rock music. Punk was rising up the charts, and the raw accessibility of the style allowed it to grow. Punk is often seen as the most legitimate form of protest music, a nihilist rally focused on tearing down the system. However, I would make the argument that disco, whose origins are in illegal queer spaces, created by minorities and in stark defiance of the status quo, is the ultimate protest music. When dancing with another man is illegal, when being femme-presenting is prohibited by law, when being homosexual is labelled as a mental illness, one realizes that the perceived hedonism and promiscuity of disco are in fact radical acts of queer protest.

Asa Williams is a writer and researcher whose work explores the intersections of literature, music, and counterculture. Currently completing a PhD at the University of East Anglia, his thesis Rock’n’Roll Rimbaud examines the influence of Arthur Rimbaud on twentieth-century American music, from the Beat poets to punk. He has spoken at conferences across Europe and the UK, and his creatie writing has been shortlisted for the Merky New Writers’ Prize and published in various books and journals. A former student of Classics at Durham University, Van Mildert College, they also write poetry and are developing a folklore-inspired anthology. Please check on his music-poetry project The Leadfoots, at @the_leadfoots on Instagram.