“Which one’s the man?” a red-faced thug jeers out the window of his Holden VL as it rolls past. He is not alone. Our tormentors were never alone. A scrum of malicious laughter emanates from deep inside the car. The pair of fluffy dice hanging from the rear-view mirror swings freely, unlike their testicles, which are tightly tucked away out of harm’s reach. As the car takes off, my new girlfriend Francine kicks an empty coke can into its wake. She curses the cowardice of men who are threatened by a couple of skinny vegan lesbians. Lacking the imagination for more creative hobbies, they drive into the city specifically to hound queers like us. “Poofter Bashing” is their sport.

We are on a mission so we keep walking, heads lowered.

“We could take down the number plate,” Francine suggests.

“What for? It’s the 80s, everyone hates gays. The police are hardly gonna help,” I reply. The guys never actually get out of their cars. They wait until the lights go green before they yell out. They are more scared of us than we are of them.

“People do get bashed though.” Nearly everyone we know has been assaulted at some point. My friend Chris got hurt really bad.

“The ‘Gay Plague’ media reports don’t help. It’s fucked.”

Australian authorities now admit publicly that, during the 1980s and 1990s, gangs of teenagers in Sydney hunted gay men and lesbians for sport, “sometimes forcing them off the cliffs to their deaths”. Police “had a reputation for hostility toward gays and often carried out perfunctory investigations that overlooked the possibility of homicide.” “New South Wales decriminalized sex between men in 1984.” The laws changed slowly but society, including the police, was slow to catch up. Lesbians didn’t register on any legal radar. Our sexuality was invisible. Unless there’s a man involved it apparently did not happen.

We cut through the park past a homeless guy rooting through his shopping trolley stuffed full of plastic bags. I look up to absorb the scene. The dried-out grass in scruffy patches of dirt mocks a gaggle of goths who sweat through their makeup in the shade of a massive tree. The fountain chokes on rubbish. The local dealer, Mr Penguin, paces the pathways in his tracksuit, arse cheeks clenched. But none of these things pose any threat to us. We feel safer walking through a park full of miscreants than along the main road.

“Which one is the man? Why do they say that? Haven’t they seen women wearing trousers?” I rant. “The violent policing of gender is just…fucking…”

“Narrow minded. Ridiculous,” offers Francine.

“Those misogynist bogans believe that every couple needs to have a designated person to be the controller, to ‘wear the pants.’ Have they no imagination? Don’t they want equality?”

For most of modern history, women could not be ‘trusted’ to be independent, run a family or a business or even be responsible for our own decisions, including the clothes we wear. In the western world, it was not socially acceptable for young women to wear trousers even up to the 1960s. In many regions, this bizarre rule was enforced not only by social custom but also by law. Only recently, the French government overturned a 200-year-old ban on women wearing trousers.

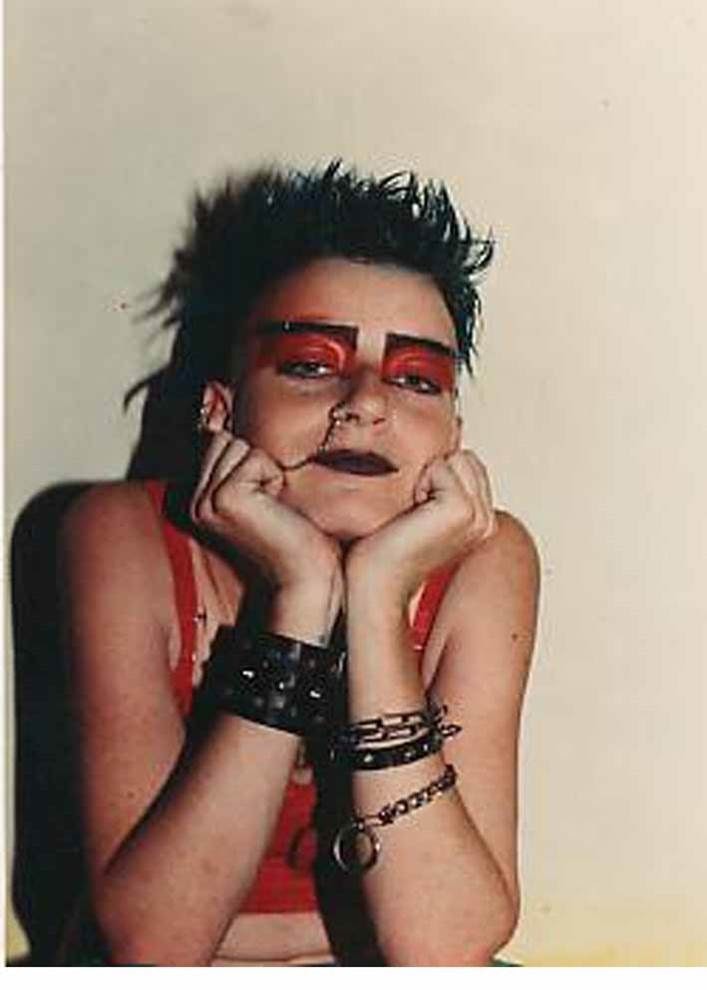

“It is not just about ripped 501s or short hair,” Francine continues, “just by looking androgynous, we threaten the very fabric of society. What kind of fabric is it? Some kind of lightweight frigging lace?”

We both crack up and set off again on our journey towards Sydney’s gay heartland for the Candlelight Rally in honour of friends lost to HIV/AIDS. Laughing helps us regain our strength. Humour is good like that.

We head down the laneways of Surry Hills. I tell Francine the story about my year as a boy. I kept my hair short and wore pants and duffle boots with a cowboy shirt, climbing trees, free to be ‘boisterous’. I wasn’t trying to be a boy, I was a boy, and a girl, but mostly a boy, at least for that year. I wanted to express my whole personality and fiercely resented any pressure to be typecast into one version. Like many kids, my expression of gender was not fixed. With boundless capacity for creative play, young children possess the secret to happiness. What happens? Until the great shame occurs, many kids are gender fluid. Young boys skip along, joyfully waving their arms about like the most flamboyant drag queen, whilst girls take charge. Boys exhibit the full emotional range. Girls construct, build, and compete. Have you ever seen a nine year old girl rock a skateboard? It is a pleasure to behold.

A couple of drag queens dazzle past as we approach Oxford Street. There are loads more of us on the street now. I relax and stay in stride with Francine, who has been listening closely but has kept quiet, not yet ready to reveal our true identity. Later he would share the story about being forced to wear ribbons and frilly dresses that made him grimace with discomfort. For now it was too painful. His yearning for gender reassignment was becoming more urgent, and soon he would find the strength to make it happen. Until then, like many dykes, Francine carefully cultivated a delectable boyish androgyny.

Crowds of queens and dykes pour onto Oxford street. I purchase a candle and a paper plate and light it for my dear friend Colin, whom I credit for rescuing me from suburban mediocrity. Colin was the cool older brother figure every young queer needs to help us realise the advantages of being a misfit. He took me to see films by John Waters, Les Girls drag shows and dancing in leather bars. He was an innovative landscape designer who once planted a ring of saplings, designed to eventually close and form a secret room, accessible only by climbing through the tangled branches above. Inside this circle, he told me about his first love, how the two lads believed they were the only teens in the world to fumble their way into gay sex. Colin told bittersweet stories like that so well. He would have loved the solemnity of this Candlelight vigil. He would have loved the internet. He would have loved.

I, too, aim for love. But love has a very different objective to the giggles of floating bubbles that rise through the body when we feel joy. Joy is the emotion of belonging. Joy is jiggly and girly and so easily smothered. The opposite of joy is not sadness, it is fear. In order to feel joy, we need to feel safe.

Francine grabs my waist, yanking me from my reverie, and points out a lone placard that reads “We are not gay as in happy; we are queer as in fuck you.” This procession does not have the glitz and glamour of Mardi Gras but it is just as political, maybe more so. Many of us are outraged. I was told by an aunty that AIDS was the ‘wrath of god’. That comment kept me from my family for a long time. Their judgement and condemnation fuelled my rejection of mainstream culture and their expectations that I, too, would want a white picket fence, big hair and Lady Di pearls. The way straight women use their femininity to vie for male attention made my stomach churn; their privilege, their racism and their condescension disgusted me.

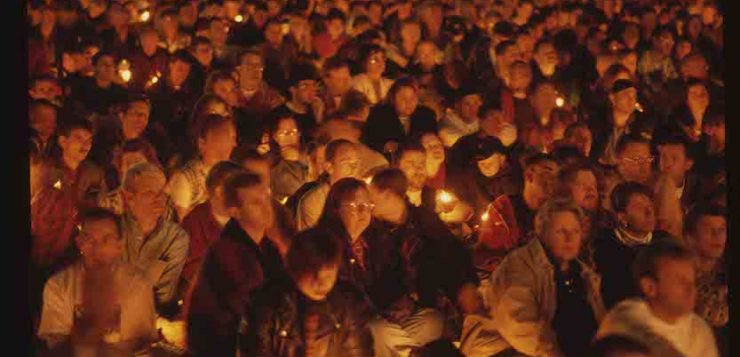

Thousands of us shuffle all the way down the hill in a beautiful dignified demonstration of respect for our loved ones lost. We reach Hyde Park to the dulcet sounds of the Solidarity Choir and settle into a field of candlelight. The misplaced religious tone is countered by the irreverent Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence antics. This year the list of names of loved ones lost goes for a really long time. When his name is read out, I whisper a prayer for my friend: “You matter. We all matter.”

Later we pound out our collective sadness with hundreds of sweaty drag queens, dykes, leather Marys and glittery gay men on a sprung dance floor. In the era of AIDs, this is how we grieve. We frolic freely because we get to live. We at least owe them that much. I reach over to Francine, who gives me a smile. A towering drag queen enters our orbit. She flicks her hair to reveal a pair of miniature fluffy dice that swing happily from her ear. The bolt of fear cast into my belly by the hooligans earlier that day dissolves into laughter and flitters up to join the twinkling disco ball lights above us. The drag queen shimmies around us mouthing the words to our anthem ‘Mighty Real’ by the Communards. Francine does her Billy Idol shuffle. My hips swing freely and a surge of joy pulses through my body.

(Note: Jasper’s former name and pronouns are used with his permission and at his request.)

Lisa Salmon is a queer writer and artist. Her memoir writing tracks her role as a provocateur in the early days of queer women’s sexual liberation when the pursuit of pleasure was a powerful political protest. She has recently been published in Archer Magazine.

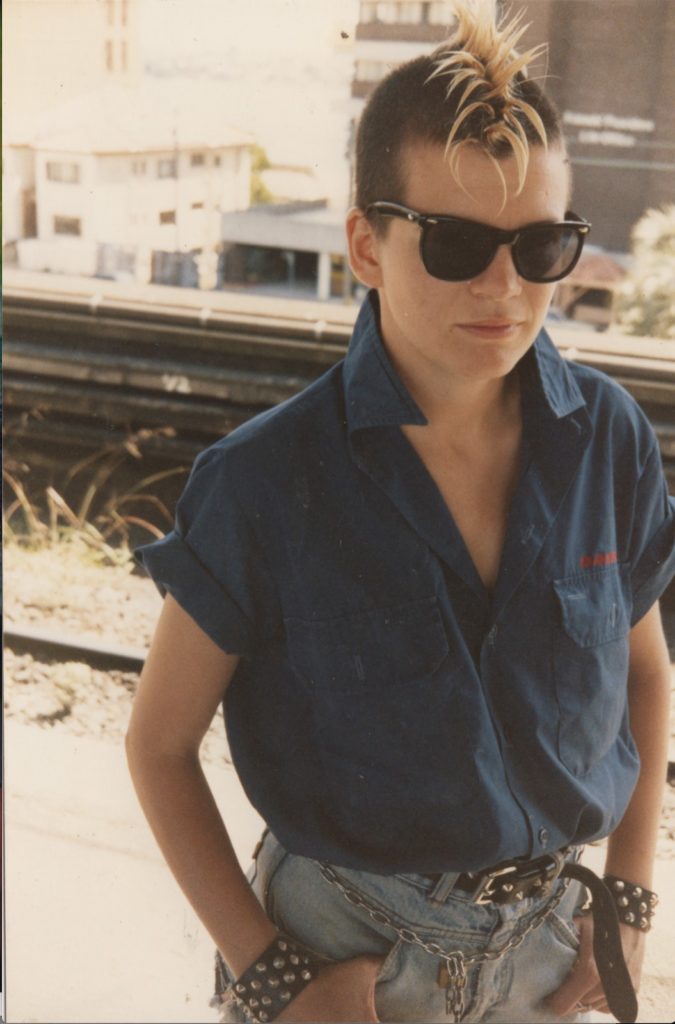

Photos are from the records of Wicked Women, courtesy Australian Queer Archives. The Australian Queer Archives (AQuA) collects, preserves and celebrates material from the lives and experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans and gender diverse, intersex, queer, Brotherboy and Sistergirl (LGBTIQ+) Australians.