STILL JETLAGGED from a late-night flight, I woke up early, had a cup of tea, and got ready to walk over to Joe’s place. I called first to let him know I was on my way. I hadn’t given any thought to how uncomfortable this might be for Joe or me, or how difficult it might be for him to open his door and allow me in. After several months of not seeing each other, I thought I would just be happy to see him, and he would be just as happy to see me.

I buzzed Joe’s suite. It took a bit of time for him to answer. I said “Hi, it’s me.”

He said, “Come on up,” in a weak voice and buzzed me in.

Stepping out of the elevator, knocking on his door, and waiting for Joe to answer was distressing—it was worse when I saw him for the first time. Mickey and Ray were right: Joe’s appearance was shocking. He was a rack of bones wrapped in his burgundy, terrycloth housecoat.

Joe said, “Scary, eh?”

I said, “No. But thin and sick looking? Yes.”

We moved onto his balcony with its million-dollar view. It was a nice enough day. Joe sat with his face to the wind. He said the wind helped him breathe more easily, that he was questioning his worth as a person while on this earth. He joked that at least he could proudly say, as a man he got to wear some really pretty dresses. In the end, we agreed that he should be proud, laughing together. He told his mother not to let the family refer to him as that fruit that died from that gay disease. He wanted her to tell them that he is her gay son who died of AIDS and it’s not a gay disease. He suggested his mother confide in those close to her so she has support when he passes. She said she had already done so.

Joe didn’t want to go home for a visit because he looked too thin and sickly. He would rather they remembered him the way he was. The only medication he took was a pill for the herpes sores that line the inside of his stomach and morphine for the pain. He knew exactly when his four hours were up and it was time to pop another morphine pill.

Before leaving, Joe wanted me to walk with him the few blocks over to Main Street so he could go to the bank. He was slow moving and unsteady on his feet. He did his best to hide his frailty. While at the bank, he snapped at someone for staring at him. He hated being stared at.

After the bank, we walked back toward his apartment, moving slowly but steadily. Halfway there, Joe became irritated with himself. He had wanted to stop in at the 7-Eleven to buy a popsicle.

Popsicles provided relief for the dry-mouth the morphine caused. I hurried back to the 7-Eleven while Joe waited on the sidewalk. When I returned, I handed the popsicle over and immediately regretted it. I should have first broken the popsicle in two. Now that Joe had it there was no way in hell he was giving it back to me. It was his opportunity to prove that he was stronger than he appeared and quite capable of breaking the damn popsicle in half. I had no choice but to stand back and watch. Joe put all his strength into breaking that popsicle in two but couldn’t do it. It ended up breaking into several pieces and fell onto the ground except for one small piece that remained on the one stick. Joe stood so vulnerable before me, and in the moment I sensed he absolutely hated me.

Watching him wrestle with the frozen popsicle took me back. I had been there before with Roger, but instead of a popsicle it was a balloon. Roger was sick and I was at his place decorating the house and blowing up balloons for his fortieth birthday. Roger sat at the kitchen table watching and decided he would help by blowing up a few balloons. I can still see him sitting at the end of the kitchen table trying with all his might to blow up a balloon. He didn’t have the lung power. Man versus kid’s party balloon and kid’s party balloon won. That failure confirmed how sick he was. He started crying and became angry, yelling, “Here I am a grown man and I can’t even blow up a fucking kid’s balloon.” That haunting memory came back to me as I watched Joe wrestle with a popsicle.

Joe and I slowly continued back to his apartment in silence. When I was leaving he demanded his house keys back and made his intentions quite clear to me: “And don’t you think you’re moving in here, Mrs. Hamilton, and taking over, because you’re not.” I showed him where I had placed his house keys on the counter, gave him a firm hug, and told him I’d be back tomorrow. I sensed he hated me even more at that moment and wished I would just stay away. Unlike with Roger, I wasn’t going to let Joe keep me at a distance. Not without a fight.

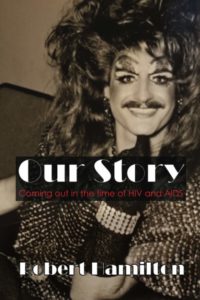

Robert Hamilton has called Vancouver home since 1982, but grew up in the small town of Northern, New Brunswick. As he reaches his golden years, it feels like he’s been writing forever – poetry, short stories, scripts for stage and film, and journaling his gay life since 1988. He is a past Canadian Film Centre Writer Resident, twice Praxis Fellow, and most recently a participant in the Playwright Theatre Centre’s Wrightspace Residency program, work shopping his current stage play, based on his memoir, OUR STORY: Coming Out in the Times of HIV and AIDS.

Robert Hamilton has called Vancouver home since 1982, but grew up in the small town of Northern, New Brunswick. As he reaches his golden years, it feels like he’s been writing forever – poetry, short stories, scripts for stage and film, and journaling his gay life since 1988. He is a past Canadian Film Centre Writer Resident, twice Praxis Fellow, and most recently a participant in the Playwright Theatre Centre’s Wrightspace Residency program, work shopping his current stage play, based on his memoir, OUR STORY: Coming Out in the Times of HIV and AIDS.

Discussion6 Comments

The popsicles reminded me of when I took care of my best friend. He had taken the back bedroom of my home and liked banana and orange popsicles so I would head out at all hours to get boxes and boxes of his popsicles. He didn’t want to go back to his apartment, maybe because he would have been alone. Even though I had a partner I’d sleep with him., after all he was my best since age 10. He died about a month later and I’m been grieving ever since, 29 years later.

How wonderful. He was lucky to have your friendship.

Thanks for this. The COVID epidemic has brought back a lot of memories of the early AIDS epidemic.

https://link.medium.com/nRRHYeMBndb

Wonderful story, bittersweet. I believe any gay man living today knows what it is like to see hell. We have watched, prayed, cried and buried our loved ones. I always think…..it could have been me. And now we have a pandemic….thank you for sharing your story. Wally Swanson, Monterey, California

Thank you for sharing such a heart -wrenching story – it’s important for the world to be reminded of what happened – to keep sharing stories and to bear witness to the devastation that was inflicted on so many lives.