Mark Merlis—author of four groundbreaking gay novels – died on August 15th 2017 in Philadelphia’s Pennsylvania Hospital. The cause of death was pneumonia, related to amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or Lou Gehrig’s disease, which he had been diagnosed with just a year ago. Aged 67, Merlis is survived by his life partner – and since 2014 husband – Robert Ashe, and two brothers.

Mark Merlis—author of four groundbreaking gay novels – died on August 15th 2017 in Philadelphia’s Pennsylvania Hospital. The cause of death was pneumonia, related to amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or Lou Gehrig’s disease, which he had been diagnosed with just a year ago. Aged 67, Merlis is survived by his life partner – and since 2014 husband – Robert Ashe, and two brothers.

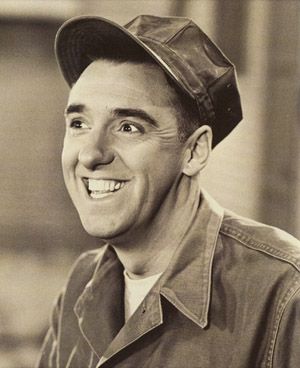

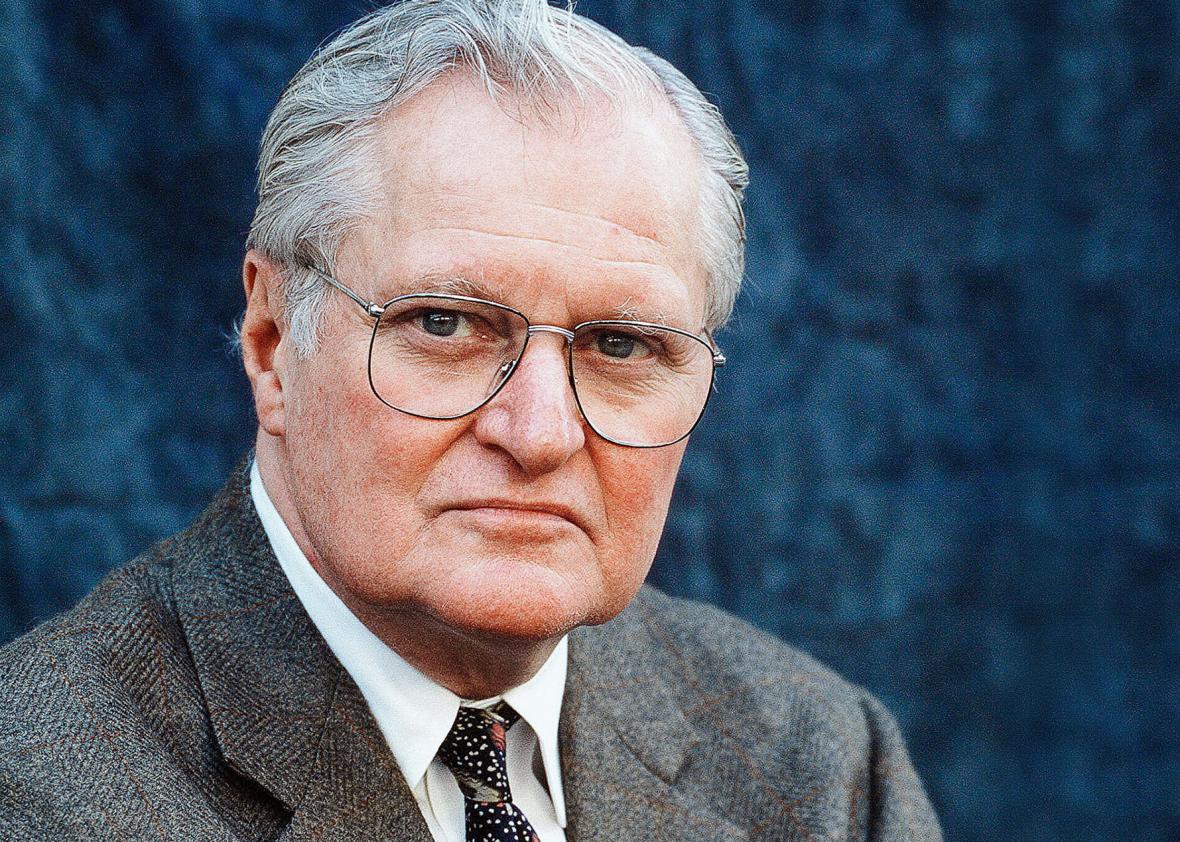

Born in 1950, he was raised in Baltimore by his Jewish father, a doctor, and Catholic mother. He earned a BA in English from Wesleyan University (1971) and an MA in American Studies from Brown University (1976). Alongside writing fiction, he had a long career in health policy consultancy which began in Maryland’s health department. Merlis moved on to the Library of Congress (1987-1995) and the Institute for Health Policy Solutions (1996-2001). Though he later referred to “tumbling into the bureaucratic life that ensnared me for the next 35 years’, he continued working freelance until he retired in 2012. He rose early, writing his fiction for two hours regularly every day, from 5:30 to 7:30am. He wrote four unpublished novels before the appearance of American Studies (1994) when he was in his mid-40s.

American Studies concerns aged narrator Reeve, bedbound in hospital after a hustler has beaten him up. He reflects on his adolescent affair with his closeted college tutor, Tom Slater, who killed himself during the McCarthyite witch hunts, and draws comparisons between their lives. Beautifully styled and structured, the novel announced the broad theme which is, to me, common to all Merlis’s output: the relationship between recent or contemporary American gay lives and values and those of preceding generations. That said, in interview in 1997, Merlis himself argued that his theme was “the conflation or confusion of sex and power. All the books try to get at something about gay sensibility that doesn’t directly have to do with sexual activity; a search for some ineffable thing which is other than sexual, and which I can’t articulate.” Merlis went on to cite Walt Whitman, America’s national poet, whose concept of male-male adhesiveness “was about something other than fucking’. American Studies won the Los Angeles Times’s Art Seidenbaum Award for First Fiction and the Ferro-Grumley Award for Distinction in Gay Writing.

His second novel An Arrow’s Flight (1998; in the UK, Pyrrhus) was his most elaborate and ambitious. It updated Sophocles’ Trojan War-era tragedy Philoctetes, relocating it—in part – to 1980s gay urban America. It stands among the most essential AIDS fictions, yet An Arrow’s Flight, Merlis himself argued, was “only really obliquely an AIDS book. One is expected to conclude that something like AIDS is going on. It’s really a “before” novel without the “after.” The novel won the Lambda Literary Award for Gay Fiction and was subsequently selected by the Publishing Triangle as one of the hundred best GLBTQ novels of all time.

Man about Town (2003), Merlis’s third, was certainly his most immediately autobiographical novel. Protagonist Joel, an advisor in healthcare on Capitol Hill, finds himself abandoned by his long-term lover and is made newly aware of the callousness, self-interest and corruption in American’s political infrastructure. As a mid-life crisis descends, Joel reverts to a childhood obsession with a seductive beachwear model, determining to trace the former object of his desires. Man about Town was widely and very well-reviewed, though its author – who held himself, like everyone else, to the very highest standards – would later dismiss it as “the novel nobody liked.”

Perhaps this disappointment informed the long gap before a fourth novel appeared. When it did, JD (2015)—standing for Juvenile Delinquent – once again showed that Merlis’s creative restlessness made him incapable of recycling anything, In each book, he delighted in taking on new forms and voices; JD is “double-narrated”. One narrator is Martha, the widow of sixties’ counterculture hero Jonathan Ascher. When approached by a would-be biographer of her husband, Martha returns to his papers. However, Ascher’s journals—which comprise the second narration—reveal her husband’s bisexual past in lurid detail. The two storylines complement each other, building a devastating portrait of marital dysfunction and deceit. The Wall Street Journal review was typical in summarizing JD as “beautifully controlled and heart-wrenching’.

I first met Mark when I interviewed him in 1997, and thereafter always sought him out whenever in the States. He was the wittiest dinner companion, and invariably happy to turn himself into the joke. I said, desperately in the interview: “It sounds as if you engage very closely with your reviews.’ Mark deadpanned: “There were so few reviews [of American Studies]that it is easy to remember them all.’

He could be artistically conservative; I don’t mean this negatively. He simply revered strong composition, craft, attention to detail and an awareness of tradition. New kids on the block and momentary fads couldn’t interest Mark. Moreover, his literary lodestars were often not in fiction. He argued in interview that “the really strong gay literary tradition is the poetic one’, by which he meant Whitman, Hopkins, Housman and Auden rather than anything recent. His “ideal fiction writer’, he offered, was George Eliot, adding: “I don’t have her scope, but I’d love to write something like Middlemarch.’

I remember vividly in 2005 suggesting a Jean-Michel Basquiat show in Brooklyn. What was I thinking? As we walked through the galleries, a long silence ensued. I felt my mistake keenly, and burbled an apology if I had wasted Mark’s time. “You didn’t,’ he responded sardonically. “This is fascinating. Every painting is bad in a different way.’

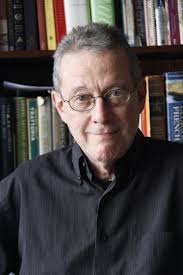

Richard Canning is the editor of Vital Signs: Essential AIDS Fiction (2007).