I often think back to a gentle statement Judith Butler makes in the 1999 preface to her influential and infamously challenging book, Gender Trouble. She reminds readers that, “there is a person here”—that person being her, whose lived experience and contexts shaped the book and its ideas. In Undoing Gender a few years later, she reveals a bit more about how she wrote that Gender Trouble, describing her younger self as “a bar dyke who spent her days reading Hegel and her evenings at a gay bar, which occasionally became a drag bar.”

I start with a reference to Butler not to be pretentious, nor to legitimate bars as foundation for queer theory. I recall these humanizing disclosures because they have shaped my own thinking about the conditions of academic thought and the labor of writing, which too often are overlooked.

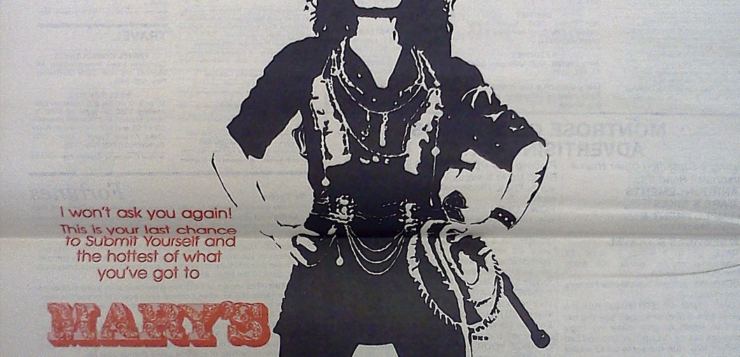

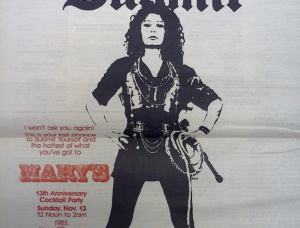

My book, The Bars Are Ours: Histories and Cultures of Gay Bars in America, 1960 and After (Duke University Press, 2023)— published after years in the works – is a book that I’ve lived with for a long time, and the way it makes contact with the past is indisputably shaped by my gay experiences and encounters. It was essential to me that book not be deadly dry, but that it find a way to convey gay histories as lived. I started work on this book because I missed the nightlife and saw the project as a kind of vicarious conjuring. I figured that we can’t understand the importance of gay bars and nightclubs without trying to understand how they made us feel, which music was playing, or what they smelled like. Because I was writing about the recent past, I knew that even if I hadn’t been to a particular bygone bar, one of my readers might have been, and they might have vivid memories of it.

Working on the book also meant going out into the world, traveling to different cities to mine archives and explore the nightlife. In the early years of working on the project, I was routinely told—while talking to someone at a gay bar—that gay bars are dying. People also regularly remarked that of course I would write about such and such a bar— whichever one seemed formative to them or loomed largely in their memory. The bars they named were rarely the same ones that the archives or back issues of gay presses pointed me toward. This mismatch reinforced that bar histories, and the sense of what venues or issues mattered, were highly personal and idiosyncratic.

Early on, strangers also often teased me, amused by the idea that going to gay bars was “research.” Almost imperceptibly, as the years went by, this shifted; people no longer thought historicizing gay bars seemed like a joke. Instead, it was something that needed doing.

Over the years, when traveling, I often took notes on my phone as a discreet way to document my observations. I figured it looked like I was texting, scrolling social media, or cruising hook-up apps like so many other people in bars. Then I would turn my typo-ridden notes into diaristic prose.

One night in Ft. Lauderdale, I went to the Alibi, a bustling burger restaurant-video/sports bar that anchors a shopping plaza. As my reflective notes explain, the venue “seems to be the kind of place where people start their night out, meeting up with friends. It has a casual feel and groups are deep in conversation. Although it’s relaxed, I can easily imagine that it’s also the kind of place where conversation and laughter get louder as the clients get progressively more drunk, and that it’s the kind of place where ‘another round’ seems like a good idea at the time.” This sort of observation-meets-speculation recurs across my travel notes.

At the Alibi, tourists from Columbus approached me and called me out for paying more attention to my phone than to them. One more gregarious person disputed my claim that I was writing notes on my phone because I wasn’t carrying a notebook. Later on, I made profiles on Grindr and Scruff, explaining in my bio that I was traveling for research. In Omaha, patrons who had seen me on the apps conspicuously talked about me within ear shot, and this provided an opening for me to engage more directly. I’m too much of an introvert to chat someone up normally, but this became a way to open the door and to learn from locals.

Whenever possible while traveling, I looked up local acquaintances for a night on the town to help me navigate the scene. Going out alone in an unfamiliar city often revealed how little I understood about the city’s geography and dynamics. I repeatedly found that Google and Yelp searches yielded outdated and unreliable information, including which bars are actually gay bars or what their peak nights are. Most online reviews of gay bars appeared to have been written by heterosexual patrons. In San Diego, I went to what I thought was a gay bar near a Naval base, but the small crowd there was straight. Another man apparently made the same mistake. It was the only time I’d ever been approached with the pick-up line, “Are you in the service?”

The most striking encounter during my research was also the most unexpected. On Super Bowl Sunday in 2017, I was midway between Dallas and Houston when was I pulled over by a highway patrolman. He asked what I was doing there, and I hesitated— calculating the risks— before responding that I was traveling to research a book on the history of gay bars in America. He called for back-up, and a stern superior officer oversaw a search of my vehicle. I was conscious that while white privilege offered me considerable protection, things would likely have gone differently if I was Black or perceived to be a person of color. But as the junior officer repacked my car, the superior officer came over and asked more questions about my research. He asked if gay bars still existed. He then told me that his young adult son is gay and that his ex-wife had left them because she could not accept their son’s sexuality. He told me that his son needed some direction but was a good kid. I think he was glad to have someone to talk to who might empathize. Amid the cognitive dissonance of the situation, I was reminded that we can’t know what other people are going through—or how many people still live without access to queer communities. Gay bars not only still exist, but we still need them.

Lucas Hilderbrand, the author of The Bars Are Ours: Histories and Cultures of Gay Bars in America, 1960 and After, is professor and chair of Film and Media Studies at the University of California, Irvine and the author of the previous books Inherent Vice: Bootleg Histories of Videotape and Copyright and Paris Is Burning: A Queer Film Classic.

Lucas Hilderbrand, the author of The Bars Are Ours: Histories and Cultures of Gay Bars in America, 1960 and After, is professor and chair of Film and Media Studies at the University of California, Irvine and the author of the previous books Inherent Vice: Bootleg Histories of Videotape and Copyright and Paris Is Burning: A Queer Film Classic.