The book flap of Notas de um filho da terra begins: “James Baldwin nasceu em Nova Iorque, em 1924, no bairro do Harlem, onde cresceu e estudou.” I purchased the European Portuguese translation of Notes of a Native Son on an impulse the day after New Year’s 2025, on my way out of Fnac, a store in Madeira. Shops had just reopened. Madeira is a small island in the Atlantic Ocean, an autonomous region of Portugal, closer to the coast of North Africa than mainland Portugal. Fnac didn’t have the toner cartridge for my European Brother printer, but I was thrilled to see a sepia book cover of Jimmy on a center aisle, his arm slender, his elbow positioned on top of a Royal typewriter, his ringed hand resting squarely on top of his head, gazing ever so slightly down, away from the photographer’s gaze. A pose, no doubt. Pensive. Almost sad, but not.

Translated by Pedro Rapoula, the edition of ten essays was published by Alfaguara “por ocasião do centenário do seu nascimento, celebrado em 2024.” Deservedly, the centennial of Baldwin’s birth was celebrated around the world, including a festival produced by La Maison Baldwin in Paris, and readings at The Library of Congress in DC, the Museum of the African Diaspora in San Francisco, among others. “Ativista, homem, negro, homossexual…” I thought Notas would be a good addition to my small collection of European Portuguese books; I purchased the book-length epic poem Omeros by Derek Wallcott in Lisbon two years ago.

My wife and I have been planning an escape to a more “neutral” environment for several years, given the MAGA movement’s overt attacks on trans kids and adults. From the resurgence of bathroom snoops, sports prohibition, government intervention of puberty blockers, to banning gender-affirming medication for trans adults altogether. Portugal continues to rank high as a friendly LGBT+ travel destination. In fact, discrimination against trans and intersex folk is illegal. Lei da Identidade de Género, the Law of Gender Identity was ratified in 2011. The chance discovery of Notas de um filho da terra felt serendipitous, given Baldwin’s lived experience, his activism, his fearlessness, and audacity to be his authentic self in life and on the page, in the United States and abroad.

What’s less well known is, James Baldwin was also a poet.

His poem Untitled begins with one word, one comma, a one-line monostitch: “Lord,”.

In her introductory essay to the collection Jimmy’s Blues and Other Poems, poet and National Book Award winner Nikky Finney speculates, “I believe he wrote poetry because poetry brought him back to the music, back to the rain.” In “Playing By Ear, Praying For Rain,” Finney makes several references to rain including, “His words fell on us like a good rain.” She also wrote, “I had needed Hansberry to set my determination forward for my journey. And I needed Baldwin to teach me about the power of rain.”

Analysis of the poem’s meaning can be found online, referencing an interview Baldwin gave about the challenges (i.e., pressure) African American artists confront daily, including the need to cater to a White cultural establishment. I haven’t read or seen the interview. But here, I am seeing and hearing something else from the poem’s narrator.

In fifteen short lines (including four monostiches), I hear a self-reflective prayer compared to Stagerlee wonders, a protest poem, also in the collection. In Stagerlee wonders, the poetic voice is justifiably outraged over the impacts of the Vietnam War, the school-to-prison pipeline, slavery… “Nigger, read this and run!”

From my point of view, the potential to change a future downpour of ponderous rain with a prayer-like spell is the poetic conceit of Untitled. The biblical connotation of rain cannot be overlooked (e.g., a symbol of God’s love), given Baldwin’s relationship to religion as a former preacher: But/And. Like all water—bad rain can damage, bad rain can sting, bad rain can flood, and bad rain can kill. Good rain heals, makes things grow, fills reservoirs. Good rain calms.

In his essay “We Are The Stars: Black Speculative Narratives and The History of the Future,” John Jennings wrote that Sheree Renée Thomas, editor of Dark Matter: A Century of Speculative Fiction from the African Diaspora “…reimagined Black literature as essentially speculative. By doing so, she posited a much earlier origin of Black speculative culture and science fiction that predated the term Afrofuturism.”

Which brings me back to Baldwin and Untitled. What of the falling water? What of the light? What of a different world Baldwin steadfastly conjured in his novels, essays, plays, and poems interrogating race, politics, and sexuality? Is that not the definition of worldbuilding?

My guess is neither Baldwin, Finney, nor previous readers of Untitled encountered a Black speculative poem. (Perhaps a non-prayer prayer.) As mentioned, the poem begins with Lord, as in have mercy, or as in Hmmpf, can you believe what girlfriend is wearing? On Instagram, you can watch a video of Billy Porter shimmering in a dress of rainbow sequins, their face fabulously made up in make-up, wearing nose jewelry, reading Untitled for their Instagram followers. Evidence Baldwin and Untitled will continue to reach new audiences.

I don’t talk to god—in prayer or poems. But I do listen to those who do.

Nikky Finney has discussed publicly Baldwin’s influence on her poetry. In an interview posted by LitHub’s The Quarantine Tapes with writer Walter Moseley (an avid supporter of the Black poetry organization Cave Canem), Finney reflects, “It is my responsibility, James Baldwin says, to tell us what it is like to love, what it is like to hate, what it is like to be loved, what it is like to feel hatred for someone, to feel the disillusionment of being whoever we are in the world. That’s where I’m going to stand for the rest of my life.”

In 2012 at Cave Canem’s summer poetry retreat, I eventually felt compelled to come out as a Black-Transman-Praying-I-Was-Passing to Nikky, an out Black lesbian and retreat faculty member at the time. Nikki Giovanni (not publicly out, but who reportedly died with her wife by her side December 9, 2024) was a visiting mentor that summer. Giovanni was another important influence on Finney’s poetry. Nikki slipped in late, but surefootedly sat down around the table with us; my poem was up for workshop. Nikki asked flatly about one word, was it the right choice? Did I mean what I wrote? I responded calmly, “yes.” After the day’s workshop, I realized from hearing several days of feedback and the great Nikki Giovanni’s question, that my work made no sense without context. Shyly, I approached Nikky Finney after a group reading. Told her my truth. “It’s all there,” she said with compassion and kindness in her eyes referring to my poems, sensing my fragility about outing myself. Her words to me—queer rain.

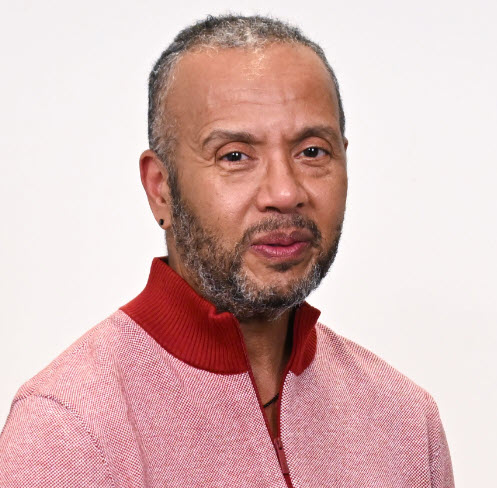

Stacy Nathaniel Jackson is a trans poet, playwright, and visual artist whose work has appeared in Callaloo, Electric Literature, and The Georgia Review, among other publications. His debut novel The Ephemera Collector was published by Liveright in 2025. More about Stacy can be found on his website.

Stacy Nathaniel Jackson is a trans poet, playwright, and visual artist whose work has appeared in Callaloo, Electric Literature, and The Georgia Review, among other publications. His debut novel The Ephemera Collector was published by Liveright in 2025. More about Stacy can be found on his website.