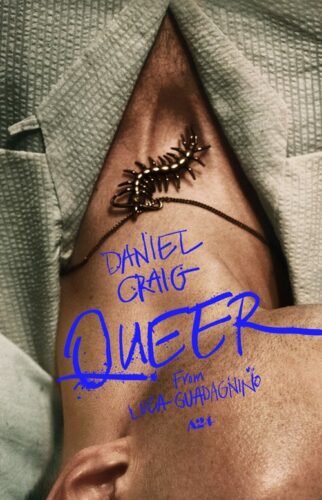

QUEER

QUEER

Directed by Luca Guadagnino

Released November 27, 2024

Like the novel by William S. Burroughs on which it is based, Luca Guadagnino’s film adaptation of Queer is less about homosexuality than about the agonies and ecstasies of being a soul trapped in an aging, alienated body. Written in the mid-1950s but not released until 1985, Queer is Burroughs’ partial sequel to 1953’s Junkie. The novel is semiautobiographical, like most of Burroughs’ works, and it centers on a group of American expatriates living in Mexico City in 1950. Among them is William Lee, who’s on the lam from American authorities after a drug bust in New Orleans. Lee, who’s addicted to alcohol, tobacco, and heroin, becomes infatuated with a recently discharged American Navy serviceman named Eugene Allerton, who is nearly thirty years his junior. Anguished by this fact, Lee is further tormented by Allerton’s ambivalence. One minute the stunning young man is unbridled in his lust, and the next he is inexplicably apathetic.

In Guadagnino’s quietly surreal and hauntingly romantic film, Lee is played by Daniel Craig, and Allerton is portrayed by Drew Starkey of the popular Netflix series Outer Banks. There are only a few sex scenes between the two men, but surely they are among the most explicit in any high-profile Hollywood production to date. There is undeniable chemistry between Craig and Starkey, and when Allerton turns cold, we can feel his cruelty as if firsthand. Guadagnino casts actors who are not just gifted but also possess an æsthetic sensibility that suits the story he is telling. This is evident in the way that Starkey looks a bit like a 25-years-younger version of Craig. Burroughs was not one for political correctness, so the fact that he perpetuates the stereotype of the narcissistic gay man should come as little surprise. Lee is undoubtedly struck by Allerton because he could be a more youthful version of himself, and Allerton knows this, which is perhaps why he cruelly toys with Lee, punishing him for his desire, until eventually we learn of his own fears, denial, confusion, and shared sense of alienation from his body. At different points in the film, both men confess to not being queer so much as “disembodied.”

Lee and Allerton travel to Quito, Ecuador, to track down yage, a key ingredient found in the drug ayahuasca, which Lee believes will provide him with a telepathic connection to Allerton. Lee hopes only to deepen their relationship and perhaps even to “become one” with him. The sublime Leslie Manville appears in the jungle as Dr. Cotter, an American physician conducting research deep in the Amazon rainforest. For Lee, yage offers the opportunity to communicate “without saying a word,” and to exorcise his loneliness and self-loathing. When Allerton downplays the hallucinogenic, spiritual experience he shared with Lee while on the drug, Dr. Cotter urges him to continue the journey and sagaciously tells him: “Now that the door is open. All you can do is look away, but why would you?”

Although Queer transcends sexuality, it is also very much about sex—sex as a distraction, as a tonic, as a form of aggression, as a mechanism by which to absorb the other. Aging is tough for everyone, and especially for gay men for whom so much of their value is found in their youth, vigor, and sex appeal. Gay men in the 1950s were clandestine creatures, having sex in the shadows, communicating in code, and concealing their identities with a life-or-death hypervigilance. Lee comes alive when Allerton is around, but when he is alone his suffering is painful to watch. His loneliness is panic-inducing.

Trent Reznor and Atticus Finch provide a sumptuous score that moves back and forth between sensuous and foreboding. Even the anachronistic use of music from Prince, Sinéad O’Connor, Nirvana, and New Order works beautifully, providing an unexpected depth and immediacy to many scenes in the film. Regarding the overall look of the film, Guadagnino cites Powell and Pressburger’s The Red Shoes as a visual inspiration. There is an intentional artificiality apparent in the sets and cinematography that only enhances the sense of living in Lee’s altered perceptions.

Exceptional supporting performances are delivered by Jason Schwartzman as Joe Guidry, a fellow expat barfly; Omar Apollo as a trick that Lee brings to a hotel early on; and Drew Droege as John Dumé, an American who organizes a gay underground circuit called the Green Lanterns. Droege captures a breed of catty gay men who take pleasure in diminishing their gay brothers with gossip, veiled insults, and subtle attempts to undermine their self-confidence.

Adapting Burroughs to film is not easy. David Cronenberg innovatively filmed his “unfilmable” concept novel Naked Lunch in 1991; and John Krokidas crafted an incisive character ensemble that’s partly about Burroughs with Kill Your Darlings (2013). But screenwriter Justin Kuritzkes (also known for the recent movie Challengers) has created a simultaneously visceral and plaintive love story with Queer. He has honored Burroughs’ complex material while also making it his own. He even furthers the morally questionable Burroughs mythology with two nods to the “William Tell act,” which resulted in the accidental shooting death of Joan Vollmer, Burroughs’ wife, in 1951, also in Mexico City.

Queer feels like a journey, even an adventure, not only to a different time and place—into the Amazon, along for a psychedelic trip—but further inward. If each person contains an entire universe, Guadagnino, like Burroughs, endeavors to chart a course for the stars, despite the deep holes that await him along the way.

Brian Alessandro co-edited Fever Spores: The Queer Reclamation of William S. Burroughs, an anthology of essays and interviews about Burroughs for Rebel Satori Press.

Brian Alessandro co-edited Fever Spores: The Queer Reclamation of William S. Burroughs, an anthology of essays and interviews about Burroughs for Rebel Satori Press.