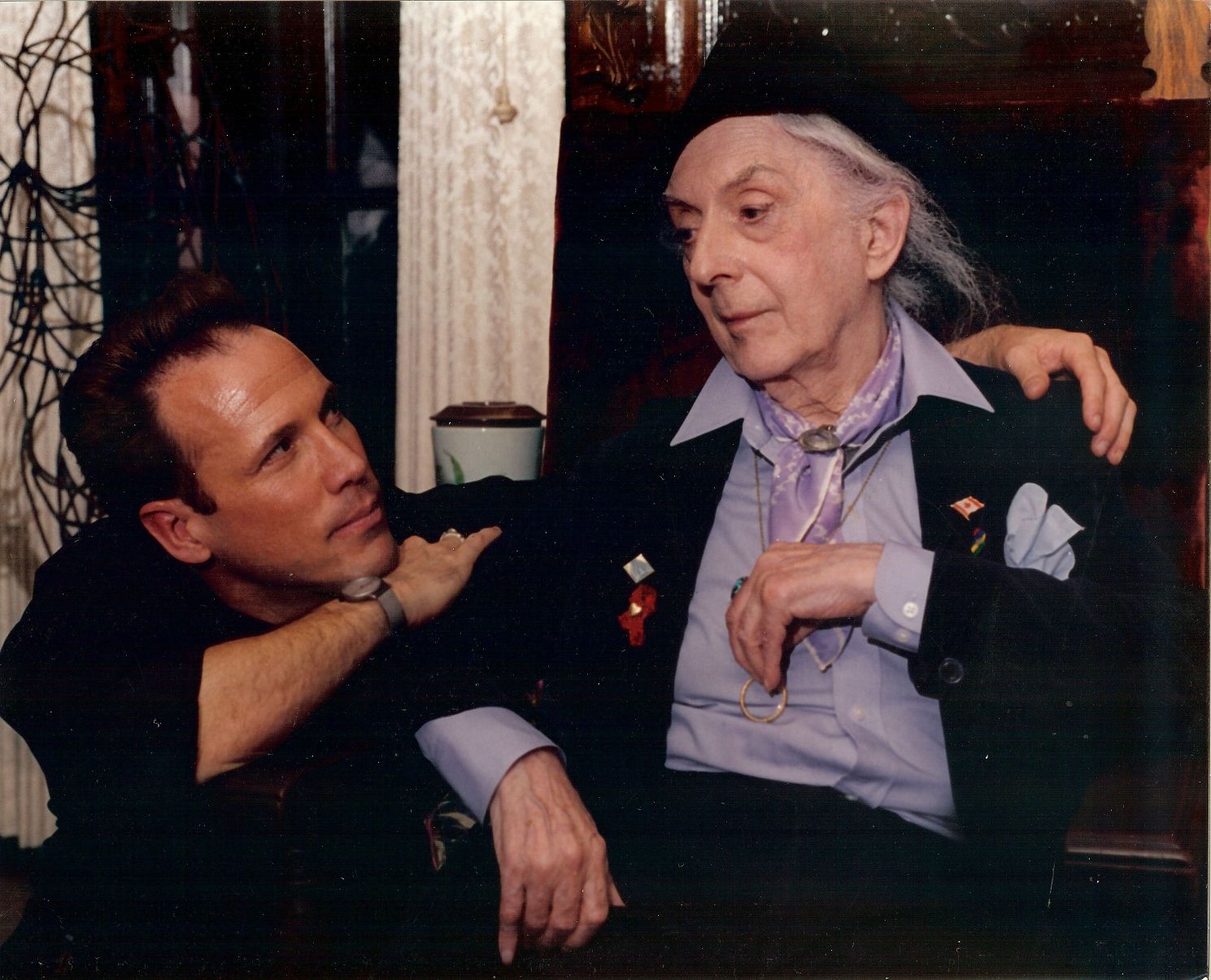

I first met Quentin Crisp in New York City in the mid ‘90s while I was on a promotional junket for my former publishing company. Mr. Crisp lived in a modest hovel on the east side of Manhattan, which he kept alarmingly unkempt for Britain’s “most famous fairy” (his words).

“After a few years, the dirt doesn’t get any worse,” was his explanation for the sordid squalor all about us when, with a colleague, I came to fetch him for lunch.

At the time, Quentin was arguably the world’s most celebrated gay author and raconteur, courtesy of his landmark autobiography The Naked Civil Servant, which had been published in 1968 and then made into a popular television drama broadcast on both British and U.S. television. His newfound fame and the film’s residuals inspired him to make the jump across the pond in 1981 to “the colonies” as he referred to them, and he promptly ensconced himself in a modest little flat in the East Village. By now, Quentin had launched a career of having other people treat him to lunch or dinner, and, like a fussy prom date, to pay for any trivial necessities he might require along the way. It was quite charming really and one did not take offense as Quentin made it seem quite the natural thing to do.

“I have always relied upon on the kindness of strangers,” he would plead by way of gratitude, unabashedly borrowing the line from Tennessee Williams.

Although most adept at inventing his own quips and one-liners, Quentin was not above borrowing phrases and witticisms from others and customizing them for his own purposes. He would twist some trite platitude inside out until it sounded original and, in so doing, breathed new life into it. “Life is a peculiar thing that happened to me on the way to my grave,” he declared to me during our premiere lunch, “and I suspect the very purpose of this unfortunate existence is to reconcile the very splendid opinion we have of ourselves with the rather appalling things that others think of us.”

In a sense, Quentin Crisp was a colossal gay cliché: a flagrant, flamboyant, theatrical old queen, complete with blue rinse, red rouge, and pink powder. He was witty, outrageous, pathetic, and perfectly glorious all at the same time! Although our maiden lunch was a thoroughly entertaining affair, I did not expect to see Quentin again but, some weeks later, I received a call from New York in that unmistakable British dowager voice informing me that he was coming to the West Coast on business and hoped I would be available to dine. Of course, I agreed and went about arranging lunches and dinners to fill the holes in his schedule and, at least meal-wise, keep him in the manner to which he had become accustomed.

A lot has been written about Quentin Crisp, and I have no desire to compare or compete with any of it. There is no question but that he caused great consternation and confusion in the gay community by calling AIDS “a fad” and homosexuality “a terrible disease,” but such was his outrageous nature, fanned by the bellows of predatory journalists seeking a provocative sound bite.

I knew Quentin in my own way for a brief moment, and our relationship was droll, endearing, poignant, sad, strictly platonic, and most enlightening—although not perhaps in the way he might have desired. I’m not sure what drew Quentin to our acquaintance other than my interest. “You have carriage and ask the right questions,” he once said by way of a compliment. “You’re irreverent but not vulgar; I like that,” he observed.

For my part, Quentin was hugely fascinating: larger than life yet authentic. He delighted in the perverse and naughty but abhorred crudity and rudeness. He accused me of knowing more than I would admit, which pleased him and amused me. “I suspect you know why the Mona Lisa is smiling,” he purred wickedly.

Above all, what I gleaned during the brief period I knew Quentin was his profound regret for those things that might have been but for his manner and circumstances. Chief among these was a true and enduring romantic bond with a kindred spirit, something he had desired his entire life and had long since given up hope of ever finding. “There is no White Knight,” Quentin declared bitterly one night after one too many cocktails. “This is an illusion you must surrender as soon as possible if you are to survive this mad and desperate existence.” He wept gently as his tears glistened in the table’s candlelight.

Fueled by alcohol, it was alarming how quickly Quentin could go from satirical and amusing to morose and bitter. My dinner guest was suddenly unleashing a lifetime of pain, abuse, humiliation, regret, and acrimony. “You must accept the inevitable, my dear; this worldly life is but a dismal and pointless enterprise of pithy lessons and earthly disappointments which are wrought by cruel and false hopes, grudgingly appointed with temporary and fleeting delusions of grandeur and triumph!”

For all his engaging anecdotes and flagrant fabulousness, it would seem that Quentin had actually existed all these years as a stranger in a strange land. “We are not friends or comrades so much as forlorn strangers passing in the night,” he wailed, “futilely searching for that gentle, romantic courtier who will lift us from our dark despair onto his noble steed and off to paradise.” By now, Quentin’s face was twisted into a tragic, haggard grimace. “No, no, my young adventurer, you must directly awaken and heed my warning,” he mourned emphatically, “There is no great White Knight!”

At that moment, looking into his sad, ancient eyes filled with vintage mascara, I realized that Quentin Crisp must be the loneliest man I had ever met. His deep melancholy was only exceeded by the abject bitterness he had learned to temper with acerbic wit and self-deprecating humor. Whether he intended to or not, Quentin instantly inspired me to ensure I would never end up with a similar outlook and, soon after, I took sober inventory of my relational worth. Quentin’s dinner rant had been a caveat.

A short time later, Quentin returned to his bohemian lifestyle in Manhattan where he continued to hold public court both there and abroad until, four years later, death took him abruptly one month before his 91st birthday.

After that fateful dinner, I vigorously dedicated myself to self-awareness. I did my homework thoroughly and discovered that the key to happiness with another individual is not about searching for an ideal relationship; it is about striving to become one—and I set about learning to do so. Now, after nearly two decades of a wonderfully intimate affiliation with a kindred soul which has weathered many a life crisis for both of us and yet filled me with endless hours of delight and contentment, I remain both grateful to and hopeful that, wherever he is now, darling old Quentin has finally found his great and elusive White Knight.

Discussion12 Comments

This was a wonderful and insightful article about Quentin who was enigmatic and outrageous in his witticism and philosophy.

He had a repertoire of monologues and sound bites he used when speaking with others.

He was sure to steer the conversation in relation to what he would reveal in a social setting. He always was an outsider and was determined to remain so.

Though he was celebrated as one of the most famous homosexuals of his era, I always felt he was transgender.

No matter, he was a unique and gifted person who got a bum steer in his early life and somehow he turned his bitterness and jaded outlook into an entertaining outlet for those who knew or tried to get to know him.

He could only engage with people at a distance, even when he was sitting across the dinner table.

I found him to be whimsical and amusingly observant in his commentary on the human condition.

I was enriched by his company.

I write to the Review in order to post an infuriated response to Tyler St Mark’s blog, “Quentin Crisp: The Loneliest Man…”. While the following observations will no doubt register as harsh, I mean to cast no aspersions generally on Mr. St. Mark as a writer. It’s how he’s handled this piece that seems to verge on the unconscionable.

.

I knew and worked with Quentin Crisp from March 1982 until his death in 1999, very nearly the complete tenure of his living in New York. I was one of his agents at Connie Clausen Associates, I did a book with him “The Wit and Wisdom of Quentin Crisp” published by Harper & Row and later Alyson Publishers (which at one memorable point involved rooming with him in a b&b in the French Quarter of New Orleans), appeared in the movie about his life in New York “Resident Alien,” wrote the foreword to Nigel Kelly’s biography of him, and have written and been interviewed about him profusely in various magazines and online venues. I reveal this merely to suggest why my claims here might be taken as credible. No one can say with any authority that he or she “knew” any human being as subtle and complex as Mr. Crisp even after an association as deep and wide as I believe mine was with him. But it’s at least credible that I may have a few more clues about the nature of the man than, on the basis of one meeting with him, Mr. St. Mark can have had. Less arguably, I can point out the screeching stylistic anomalies in the words Mr. St. Mark wants us to believe Quentin uttered.

.

Very little in Mr. St. Mark’s account of him here rings even remotely true. His alleged quotes would have choked the Quentin Crisp I knew had somebody tried to force him to say them: “You must accept the inevitable, my dear; this worldly life is but a dismal and pointless enterprise of pithy lessons and earthly disappointments which are wrought by cruel and false hopes, grudgingly appointed with temporary and fleeting delusions of grandeur and triumph!” It reads like a bad parody of some part thank heavens Greta Garbo wasn’t required to play. He never spoke in this terribly artificial way. It’s like Mr. St Mark tried to imagine what his idea of an over-articulate Royal drag queen would say on stage somewhere. Quentin was incredibly concise. Awkard, needless or imprecise adjectives and phrases such “grudgingly” and “pithy lessons” or the redundant “temporary and fleeting” just don’t add up to Quentin ever spoke or wrote. “You must accept the inevitable, my dear”? (I would stake my life on his having never vocally addressed anyone as “my dear” except perhaps in writing as a polite part of the formal address to someone in a letter.) And this speechy tract he is alleged to have “wailed”: “We are not friends or comrades so much as forlorn strangers passing in the night,” he wailed, “futilely searching for that gentle, romantic courtier who will lift us from our dark despair onto his noble steed and off to paradise.” By now, Quentin’s face was twisted into a tragic, haggard grimace.” The whole thing reads like a very bad bodice-ripper novel. The cliché “forlorn strangers passing in the night” is as un-Crispian as can be imagined. The awkwardness of the adverb “futilely” alone would have consigned it for Quentin to oblivion. “No, no, my young adventurer, you must directly awaken and heed my warning,” he mourned emphatically, “There is no great White Knight!” Quentin never addressed anyone with Victorian words like these: “my young adventurer”… “you must directly awaken and heed my warning?’” and certainly was unlikely to have mouthed “great White Knight?” Quentin’s far more subtle and powerful phrase for the sought-after paragon who did not exist was (as he than once wrote and said) “great dark man.”

I dare Mr. St. Marks to prove that Quentin said any of this. (I don’t even ask if he has it on tape, because he couldn’t possibly.) It’s speechifying of a kind that Quentin wouldn’t have stooped even to satirize because it was too badly done to pay attention to. And then to have the gall, on the basis of what I can most kindly imagine was Mr. St. Mark’s ill-remembered single evening with Quentin, to make this summary pronouncement: “Fueled by alcohol, it was alarming how quickly Quentin could go from satirical and amusing to morose and bitter. My dinner guest was suddenly unleashing a lifetime of pain, abuse, humiliation, regret, and acrimony.” This is bad pulp fiction. Since Mr. St. Mark hadn’t convinced Quentin had (or could have) said any single word he’s imputed to have said, how can I accept the summation? Especially because Quentin so often publicly and privately put the lie to it.

.

Quentin has been marvelously articulate about the nature of his own regret, pain, humiliation, etc. in his writing, always striking the note ultimately that he accepted it and had gone on. I’ve had untold lengthy conversations about his life with him. His observations were always starkly honest and (not least as a result of his unsentimental clarity) incredibly funny as well. But he was never bathetic. It wasn’t in him to be.

.

Maybe in reconstituting what he thought was true about Quentin Mr. St. Mark imagined (in some arch travesty of Victorian prose) that these words were what had Quentin had actually said. But they can’t have been. If Mr. St. Mark had made something up which underscored the remarkable truths about Quentin, not that he was any means a saint, but that he was direct and subtle and incredibly funny and precise and rolled out his stories because he’d worked on them very hard and they were as completely a part of him as his appearance: i.e., that there was very little difference between who you saw and who he was, I’d have applauded it. (As Quentin’s close reader and editor I would also easily have done what I just did here: to sort out what he was likely and not likely to have said.)

.

But sadly what Mr. St. Mark mostly misses is one of the most salient facts about Quentin: how happy he actually was. Not “happy” in a manner that would have erased Quentin’s very clear and unsentimental existential takes on life, including his own, but in the simplest and clearest ways: he liked the people and he liked where he lived and he liked the attention he got. It was better than he’d enjoyed anywhere else before. He was vibrantly glad to be in New York. (His first comment on arrival: “The moment I saw Manhattan, I wanted it!” And he got it.) More broadly, this was part of a message he proclaimed by his own words and example, that happiness was achievable, and sacrificing none of his complex self-awareness (which accepted darkness and death), Quentin Crisp demonstrated that to anyone who was paying attention.

.

But to use this supposed moment with Quentin as a means, by way of supposed contrast, to celebrate Mr. St Mark’s assessment of himself — the growth of his own wisdom and self-understanding and the wherewithal to become a worthy partner in a love relationship — is repellent, because the “contrast” part of the equation that Quentin is made to embody is so self-evidently false. By the evidence he gives, Mr. St. Mark never even saw the man across from him at that dinner. If he had, he might have been humbled by the experience. He’d certainly have been less likely to write anything as false and self-aggrandizing as this.

.

I can’t bear for the world to have this be the last word on Quentin. (Not, of course, that there will be ever a last word on him.) It is so alien to the true nature of the man.

.

Guy Kettelhack

September 18, 2019

New York, N.Y.

Bravo. Tyler St. Mark as he calls himself now uses the article to carve out a little place in a world that he didn’t have the courage to dwell in. He was willing to fabricate and distort a vague remembrance already steeped in inaccuracies hoping some of the notority would shine in his direction. Sadly none of these fabrications were conjured to focus light on the subject at hand but perpetrated in sad attempt to align himself as one of the cool kids.

Thank you Aaron. I don’t know what Mr. St. Mark’s intentions were, but the result as I’ve suggested in these pages is an egregiously inaccurate reflection of the man, both in the supposed quotes imputed to Quentin, which are unbelievable on grounds of style (an unforgivable lapse) as well as most of their content, and in Mr. St. Mark’s bathetic summation of him as a sad, drunk and lonely man at the end. In the last 18 or so years of his life (since coming to live in New York), Quentin was what he said and wrote he was: happier than he’d ever been, enormously the result of leaving England and coming to this country. I believe I can lay claim to having known him as well as anyone knew him, as friend, co-agent, collaborator and occasional editor for 17 years, virtually his entire tenure in New York. While Quentin was no stranger to irony (which of course he employed deliciously in his writing and talk) he was remarkably un-ironic in his self-assessment. What he was, was grateful to the world for having in some measure revised its initial negative opinion of him – a change of public response which flowered overall into a great and deserved esteem. But gratitude, arguably at the heart of happiness, was perhaps the most prevailing aspect of his character. I apologize for going on this long: but I stand by what I said initially in these pages, and thanks for being the only respondent herein so far to corroborate much of the reason for my response to Mr. St. Mark’s piece.

Guy Kettelhack, New York NY, May 17, 2021

Thank you for responding to the article. It doesn’t quite ring true, not just the hammy quotes but it contradicts Mr Crisps words in print and in interviews (plenty on YouTube), his thoughts on life and humanity. I wonder what Penny Arcade would think of this article.

This is a brilliant response, and I agree. I knew Quentin to some degree for the last 2 years of his life. The “my dear” and long-winded quotes of complete despair sound very contrived/ embellished. While he did utter a few hilarious observations here and there, he generally spoke normally in conversation. He drank casually, as most people do, and it is very unlikely he would weep in front of a stranger. He was British, for Christ’s sake! Ha! Above all, he certainly did not grieve the absence of a man in his life. He was far beyond that by the mid-1990s. Face to face, he would never give unsolicited advice about the subject, either. He would have found such a gesture to be presumptuous.

I am writing this article due to Mr. Kettelhack’s response to Tyler’s poignant article. I think it’s sad that some people have to throw in their opinion about other people’s experiences rather than just expressing their own but I believe Mr. Kettelhack’s true intentions were revealed in the second paragraph shamefully plugging his book while trying to discredit a fellow writer.

I believe Shakespeare said, “Thou dost protest too much,” and Mr. Kettleback certainly offered a barrage of protest. He has asked Tyler to prove what that he claims Mr. Crisp said is true. Well, Mr. Crisp was in fact speaking to me regarding my “waiting for a White Knight.” I was sitting next to him at the table that night. Tyler chose not to involve close friends in describing that dinner among several he set up during Mr. Crisp’s stay in Los Angeles but there were several witnesses to that particular conversation including myself.

It is sad when people like Mr. Kettlehack are so sure of his opinion even in the face of witnesses like me who have no book to peddle, no ax to grind, and no personal agenda here. I never met Quentin before that night or after, but his personal demons certainly flared after a few drinks and his bitterness practically glowed in the dark. I was there, sir!

It is nice that Mr. Kettleback worked with Mr. Crisp for so long on a professional level but maybe never at a level where Mr. Crisp was able to let his hair down fully and be comfortable around the company he was keeping which is what he did with us during that dinner. Or maybe Mr. Crisp was just showing off and being outrageous, I don’t know. I do know that Tyler’s interpretation of Mr. Crisp that night is spot-on, and it is sad that a fellow writer would treat a writing forum as this one and a fellow writer with less respect than Facebook. Tyler’s intentions were honorable in his story and maybe Mr. Kettelhack’s intentions are as well but maybe he was too close to Mr. Crisp professionally to have as insightful and honest a perspective as Mr. St. Mark provided in his article.

I think Mr. Kettleback owes Mr. St. Mark an apology.

Greg Money

September 23, 2019

San Luis Obispo, CA

Dear Greg Money —

My observations were written out of a deep sense of Quentin having been misrepresented. As for this being some sort of show-boating on my part, my book with him is out of print so I’m hardly plugging that. I have nothing to plug. I understand that my language was severe but when I reviewed (numerous times) what I said, I felt they needed to be heard.

I appreciate your responding to them.

Best wishes,

Guy Kettelhack

Mr. Kettelhack,

I too have to take issue with your harsh criticism of Mr. St. Mark.

I knew Quentin for his remaining years in life and having no reason other than friendship to have spent time with him, he was maybe more inclined to be vocal about some of his sorrows and regrets living as he did and feeling like an alien throughout his years in a world who made him a pariah! He was world weary when I knew him.

I think Tyler St.Mark was correct in describing Madame Crisp as a Victorian character! She was right out of a script of an Oscar Wilde play!

I am glad that Quentin lived long enough to finally get some notoriety and respect by the people who made him feel so unwelcome and freakish in his youth.

I was not fortunate enough to have met Mr. Crisp in person, but he—in his unabashed refusal to be other than himself at all times—inspired me in 1983 at age 15 to come out of the closet to my classmates, teachers and family. His integrity and genuineness have been traits I’ve tried to emulate, with varying success at times.

Despite the systemic abuse and homophobia that society had implemented to beat down people like Crisp, he always seemed to carry himself with a lightness and dignity that seem to me proof of his brilliance: Not many could land the role of Lady Bracknell on Broadway on sheer strength of character. But that’s what he had.

Thank you so much for writing this, it is wonderful to read this more intimate account of Crisp from somebody whom he obviously considered to be a trusted friend.

Alienating without intent

Was a time when Quentin Crisp,

Couldn’t sound his “R’s”,

And then developed a lisp,

Said he’d met a man from Mars….

Too many jars?

Hailed him with,

“I’m Quentin Cwithp”.

Interesting article, did Carol Bradshaw intend the bum steer pun?

Um: I never heard him lithp. And I knew and worked with and lived only a few blocks away from him pretty much nonstop in the 17 years of his New York existence. Of course I never heard him sing – more’s the pity! – “Put on your Sunday clothes when you feel down and out” either.

Guy Kettelhack

New York City