Queering the Crip, Cripping the Queer

Schwules Museum, Berlin, Germany

Kenny Fries, Curator

Sept. 2, 2022 – May 29, 2023

Queering the Crip, Cripping the Queer features art which showcases parallels in the experience of disabled and LGBT people, featuring the works of over twenty contemporary artists. The exhibit is currently being held in cooperation with a performance festival of the same name at the Berlin’s Sophiensaele Theater. The Disability studies scholar Carrie Sandahl originated the phrase used for the exhibit’s title.

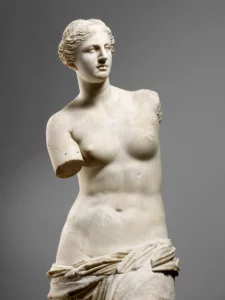

I. “The Ideal Body”

The exhibit is divided into eight sections, the first of which is “The Ideal Body,” a natural place to begin, since the disabled body is usually defined as the opposite. This section displays reproductions of the Venus de Milo and Torso of Doryphoros statue with head as disabled bodies missing arms, exploring how a body image ideal can inspire, but also stigmatize and cause psychic pain to those whose bodies do not conform to such an idealized standard; and notes how people with disabilities are seldom represented in art and literature, and the representation they are given might be metaphorical, intangible proof of their existence. Examples of this metaphorical use include characters like ancient Greece’s blind Tiresias, as well other blind figures who were believed to possess a kind of “second sight,” or special wisdom; and the blind priest singers of ancient Japan who helped forge Japanese culture while being segregated from the greater society.

II. Saints and Sinners

“Saints and Sinners,” examines how disability and same-sex romantic/sexual relationships were treated during Europe’s medieval period. Curator Kenny Fries comments, “The medieval view sees disabled people as totally evil or totally saintly and, as we know, no one is totally evil or totally saintly.” This section notes that, in non-Western cultures, disabled people were often stigmatized, for example the Hindu/Buddhist belief in karma meant disabilities were viewed as punishments for wrong-doings in past lives. As a result, disabled people tended to live in poverty and were often beggars. Disabled performance artist Claire Cunningham’s video installation “Give Me a Reason to Live,” is featured here. She was inspired by a series of drawings by medieval artist Hieronymus Bosch. “They were all of beggars, about thirty beggars, and all cripples,” she recalls. “For disabled people, being beggars or minstrels were about the only ways of surviving.” The person who showed these drawings to Cunningham suggested the disabled beggars might “symbolize sin.” Cunningham, who has osteoporosis, showcases various body movements with her crutches in her video.

The second section also discusses how medieval Europe enacted laws outlawing same-sex acts of PDA. Applying to women as well as men, medieval anti-sodomy laws, when prosecuted, were often punishable by death. As was true in medieval Europe, disabled people in today’s America may have to beg to survive.

III. The Power of Depiction

“The Power of Depiction,”explores disabled people depicted in art and literature as objects of ridicule, or figures of evil. For example, a villain might be given an eye patch or hook to symbolize a bitterness or wickedness. Disability studies scholar Vicki Lewis points out that this prejudiced tradition continues today, stating, “Introductory screenwriting manuals even recommend aspiring writers give their villain a limp or an amputated limb.” The art in this section includes a portrait series entitled Circle Stories by Reva Lehrer, an American painter born with spina bifida. She depicts disabled people who have explored body issues in their work as academics and artists. Lehrer’s self-portrait, 66 Degrees, a painting in which she is shown outdoors, with her back to the viewer is exhibited here. In this painting, Lehrer underlines “The Power of Depiction” to work positively as her disabled body is portrayed as a beautiful body at home in the beauty of nature.

IV. Perfecting…

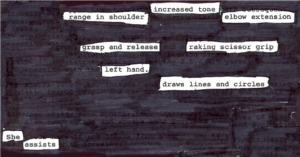

“Perfecting…,” explores body ideals in the time of Europe’s Enlightenment. The Enlightenment, also called the Age of Reason, popularized ideals of freedom and equality that inspired rebellion against traditions of monarchical rule, emphasizing the idea that we should solve problems through reason rather than cling to outmoded traditions. However, many of the prominent intellectuals of this time still clung to traditions of racism, sexism, ableism, and homophobia. The work of New Zealand’s Pelenakeke Brown, a disabled woman of Samoan/Pakeha ethnicity, is featured in this section, and showcases her hand-crafted prints entitled grasp + release, which incorporate her personal medical file from 2018. She blacked out everything from the report except for specific words, which express the feelings she wanted to convey. In a print titled, “her return,” the words left after others have been blacked out, state: “Her/return/is/to speak.” Within the “mostly foreign, cold medical terms” she draws forth “surprising glimpses” of humanity. Of this work, she has said, “Requesting this information about myself felt subversive.”

V. Enforcing/Resisting “Normalcy”

“Enforcing/Resisting ‘Normalcy’” showcases the work of Steven Solbrig, an artist born into the GDR (what was known in the United States as communist East Germany). Solbrig created a series of photographs entitled Unmatched Touch in which he demonstrates how, “the queer/disabled body resists such normalization.”

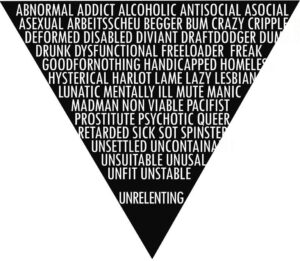

VI. Elimination

“Elimination,” addresses Nazi Germany’s mistreatment of disabled and LGBT people. Canadian artist Elizabeth Sweeney contributes The Unrelenting, which begins with a large, upside-down triangle hanging outside the museum. Against the triangle’s black background, stigmatizing words like “cripple” and “pansy” appear in white, followed by the word “unrelenting,” which describes the unrelenting persecution visited on many select groups in Nazi Germany, as well as the unrelenting will to survive among those persecuted. Perhaps what makes “Elimination” such an emotionally moving section is that it shows how this most hateful of tyrannies might be viewed as the murderous culmination of centuries of rejection of those human beings considered unacceptable by the larger society. The persecutions of disabled people committed in previous centuries — and dramatized in previous sections — found their horrendous ultimate end point in the policies of “The Final Soution” followed by Nazi Germany.

VII. Our Icons

“Our Icons” features works by Audre Lorde, Lorenza Bottner, and Raimund Hoghe. Bottner was armless and created art using her foot, including works re-imaging herself as Venus de Milo. In such works, she demonstrated how beautiful the “crip” body can be. Hoghe was born with scoliosis. A video shows Hoghe gracefully and confidently dancing with a partner to Swan Lake. Photographs and posters pay tribute to Lorde who proudly declared herself, “Black, lesbian, feminist, warrior, poet, mother,” and created powerful art out of blending these different identities. When she was diagnosed with cancer, she wrote the books The Cancer Journals (1980) and A Burst of Light (1988), in which she challenged the tendency to see someone battling a disease in terms of pathology. She wrote, “The struggle with cancer now informs all my days, but it is only another face of that continuing battle for self-determination that Black women fight daily, often in triumph.” These “icons” cleared the way for fresh approaches to our bodies. They challenged harmful perceptions of pathology and disability that led to a sense of community among the disabled, which led to demands that society make appropriate accommodations for disabled people so that the talents of all people can find full and free expression.

VIII. Freak Out

“Freak Out” is the final section of the exhibit, which as a whole shows how, over time, LGBT people have reclaimed the word “queer” and how disabled people have reclaimed “crip” and “freak,” transforming words intended to harm and ostracize them into terms of pride, strength, and community. It notes there is still much to be done so the website encourages people to “keep freaking out!”

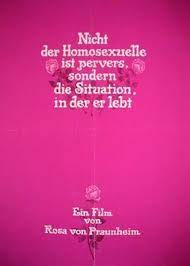

Rosa von Praunheim’s iconic 1971 film, It Is Not the Homosexual Who Is Perverse But the Society in which He Lives, that spurred West Germany’s gay liberation movement is highlighted here. Director Rosa von Praunheim is a gay man, and this film tells a story of fictional gay characters living their lives. The movie was a turning point in West Germany because many followed Daniel’s lead in organizing to demand an end to discrimination against gays.

Queering the Crip, Cripping the Queer is an enthralling art exhibit. It showcases the artistic talents and skills in the overlapping queer and crip communities. It brings to light shared histories of misunderstanding, bigotry, persecution, but most importantly, shared histories of resilience. What’s more, it underlines the special sense of alienation suffered by those who belong to both the disabled and LGBT communities as well as the special strengths that grow from making sense — making art — out of these identities.

Denise Noe is a severely and multiply disabled author. Her most recently published books are A Sheep in Wolf’s Clothing: The Life of Marie Windsor and I Spy, You Spy, They Spy. She believes some of her most powerful articles are in “The Bloodied and the Broken” and “Justice Gone Haywire.” She is interested in literature, movies, science, and social welfare issues. She is always looking for work as a writer or proofreader.