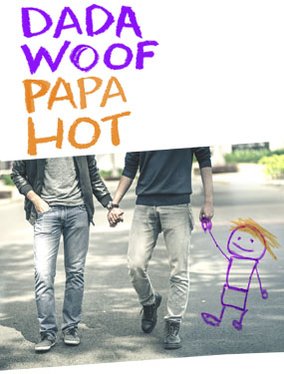

Dada Woof Papa Hot

Dada Woof Papa Hot

A play by Peter Parnell

Directed by Scott Ellis

At the Lincoln Center Theater

IN OUR AGE of same-sex marriage and parenting, a play titled Dada Woof Papa Hot seems sure to tap into the GLBT zeitgeist. Playwright Peter Parnell, as if to pick up where Terrence McNally left off, gives us a slice of gay life à la the haute bourgeoisie. This approach might grate on those who consider swank West Village living rooms and smug theatrical banter the height of white provincialism, but for those living in or near that world—which includes many subscribers to the Lincoln Center Theater—the play is an opportunity to examine how we live now, for better or worse. Parnell offers equal parts witty repartee and painful soul-searching—not a bad combination if he can pull it off. And he does.

Director Scott Ellis—Broadway’s ubiquitous Mr. Ellis—has assembled a pitch-perfect cast, led by John Benjamin Hickey, whose lanky, creased handsomeness and honey-warm voice are matched by Patrick Breen’s elfin demeanor and intellectual rigor. They play a married couple, Alan and Rob, with a three-year-old daughter who is occasionally heard off-stage but never seen. Her first words, though not blurted successively, were “papa” and “dada” to distinguish between her two fathers. “Woof” designated a dog, and “hot”—well, we can be sure it wasn’t about sex. Strung together as “papa woof dada hot,” Alan tells us that he and Rob realized they were the four words that every gay father wants to hear.

Alan is a successful freelance writer for A-list publications like The New Yorker who is trying to get a book proposal ready to sell. Rob is the steadier wage earner, a psychotherapist of some kind, and judging by the couple’s chic living space, created by veteran set designer John Lee Beatty, Rob’s hourly rate can’t be shabby.

The play is a series of sharply written scenes setting the pair up with other parenting couples: Alan’s best friend from college, Mike, and his wife Serena, whose solid marriage may be floundering; scenes with a younger gay couple in New York and on Fire Island. While the vicissitudes of raising children may bond Alan and Rob with these other couples, the difference for them as a gay couple in early middle age is that they took on parenting roles with different expectations and motives. While Alan was never a tomcat in the pre-AIDS gay scene, and while he accepted that the somewhat younger Rob would be the biological father of their child, his sharp turn into domesticity and filial devotion shakes his sense of gay identity and his self-confidence in general. He believes their little girl is fonder of Rob, but ashamed of his competitive feelings over the girl’s affections, he also suffers a sense of professional insecurity as a writer struggling to move forward on an ambitious project.

Their straight friends, Michael and Serena, seem solidly at home in their marriage—that is, until Michael reveals to Alan that he’s having an affair. While Alan disapproves and tries to set his old college friend “straight” about this ethical lapse, this revelation sets off an internal bell that encourages Alan’s own curiosity. He surprises himself by responding to an overture from a younger gay man. Meanwhile, Scott and Jason—newer friends who are younger than Alan and Rob by at least a decade—are a match of opposites: Scott is a Wall Street type with conservative politics, Jason a painter with a languid sexuality that’s barely kept in check.

Parnell is tackling the evolution of gay life from outlaw status to domestic middle-class “bliss,” from pre-AIDS experimentation to U.S. Supreme Court-approved marriage and, with children in the picture, the possibility of diminishing sexual activity over the long haul. The able cast fleshes out several recognizable urban types, straight and gay, with appropriate behavioral tics. This is a play of knowing apercus delivered by actors who’ve been around the block a few times. At one point, complimented on looking so marvelous thanks to a regular gym trainer, the maturing Alan admits that he never looked so good—or felt so old.

The social landscape here is a progression from the Terrence McNally universe of The Lisbon Traviata, Love! Valour! Compassion!, and Lips Together Teeth Apart. AIDS gave heft to McNally’s L!V!C!, even if the universe was mostly upscale white gay men. Here in Parnell’s Dada Woof Papa Hot, the verdict is out on whether or not assimilation—bourgeois marriage and fatherhood—will enrich gay experience and still allow it to remain recognizably “gay.” There is also a fleetingly acknowledged undercurrent that runs through the text: in New York City, parenting is an expensive proposition, and it may be that the experience of raising children is a privilege reserved only for gay men and women of means. After all, there’s still the rent or mortgage to pay, along with the bills for pre-K and private school.

Allen Ellenzweig is a regular contributor to The G&LR.