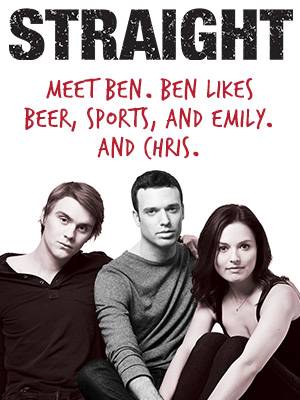

Straight.

Straight.

A play by Scott Elmegreen and Drew Fornarola.

Directed by Andy Sandberg.

At the Acorn Theatre, NYC.

THE SITUATION that confronts the central character of Straight could not be more straightforward, as it were, bordering as it does on cliché: Ben (played by Jake Epstein) is a man whose primary attraction is to other males, but he can’t bring himself to come out as gay, or at least to label himself as such, so he tries his best to live the life of a straight man. Like many men who’ve found themselves in this situation—both in literature and in the real world—Ben ends up living a double life, projecting a public persona that includes in his case a real-life girlfriend, Emily (Jenna Gavigan), even as he carries on a secret life of casual sexual encounters. The success of this strategy depends upon the brevity and anonymity of these engagements; what complicates things for Ben, who’s 26, is that he starts to have feelings for one of his tricks, a college kid named Chris (Thomas E. Sullivan). He and Chris start spending weekends together, which a) makes it much harder for Ben to keep the affair from Emily, and b) deeply challenges his self-image as a beer-drinking, sports-loving straight guy.

If the basic premise sounds a little dated—wasn’t this done in The Boys in the Band?—that is very much the point. Even in this age of same-sex marriage and openly gay celebrities, the act of coming out is still fraught and by no means inevitable for many people, while the closet endures in all its dark intrigue: the secret trysts, the lying that ensues, and the guilt that comes with it. This being not the 1970s but the 2010s, Ben is presented not as a tragic character who suffers in silence but instead a wisecracking dude whose ironic façade makes it hard to know when he’s kidding and when he’s serious. Indeed, at one point, amid much verbal foolishness, he utters the words “I’m gay” to Emily, who assumes he’s only clowning. And while Emily is an earnest microbiologist who rattles on about her experiments with mice, Chris is if anything even more ironically evasive than Ben, resulting in conversations that often leave both men confused about where they stand.

Eventually, though, the need to confront the reality of their situation forces Ben and Chris to drop the cool and talk about their future together, if any—and here they even get a bit philosophical in exploring what it means to be “gay” in our time. Chris is quite aware of Emily’s existence and grasps his precarious status as the secret lover. When he confronts Ben about the ongoing fiction of his straight identity, Ben doesn’t deny his same-sex orientation but refuses to accept the G-word as an identity. “Once you call yourself ‘gay,’” he protests, “you’re no longer Chris; now you’re ‘gay Chris’”—and all that this implies in terms of cultural commitments and social expectations. Ben is even familiar with the rather arcane debate over “behavior” versus “identity” and insists that what one does in bed should not be a person’s defining attribute. It’s a view that many young people seem to have embraced, and doubtless the whole idea of sexual identity has been slipping and sliding in this LGBTQETC age of ours. Nevertheless, Ben is surely not alone in his conviction that the choice is effectively binary as it presents itself in the real world of family members and coworkers. He will have to commit himself one way or the other and put his money where his mouth is, so to speak.

Whether Ben is in fact “gay” in the conventional (sexual) sense is initially open to question, and Straight takes its time in providing an answer. At first we’re led to believe that his loyalties are about equally divided between Chris and Emily—okay, so he’s bi—but in time we discover, along with Ben himself, that not only is the sex much better with Chris, he’s also falling in love with him. This being the case, the fact that Ben’s choice is not a no-brainer, that he refuses simply to end things with Emily, attests to the strength of his resistance to giving up his “straight” identity. That Ben is an investment banker with a lucrative career path may well be a factor, but the message of Straight—as its title suggests—is that the requirement to choose a label presents itself as an irrevocable turning point, a lady-or-the-tiger decision that cannot be avoided. Not to give the ending away, but suffice it to say there is really no satisfactory way for Ben to resolve this quandary. It may just be that the success of identity politics as a political strategy, as a path to equal rights, carries with it a subtle tyranny that its advocates never foresaw.

Whether Ben is in fact “gay” in the conventional (sexual) sense is initially open to question, and Straight takes its time in providing an answer. At first we’re led to believe that his loyalties are about equally divided between Chris and Emily—okay, so he’s bi—but in time we discover, along with Ben himself, that not only is the sex much better with Chris, he’s also falling in love with him. This being the case, the fact that Ben’s choice is not a no-brainer, that he refuses simply to end things with Emily, attests to the strength of his resistance to giving up his “straight” identity. That Ben is an investment banker with a lucrative career path may well be a factor, but the message of Straight—as its title suggests—is that the requirement to choose a label presents itself as an irrevocable turning point, a lady-or-the-tiger decision that cannot be avoided. Not to give the ending away, but suffice it to say there is really no satisfactory way for Ben to resolve this quandary. It may just be that the success of identity politics as a political strategy, as a path to equal rights, carries with it a subtle tyranny that its advocates never foresaw.

Discussion1 Comment

Funny how straight people never agonize over the “tyranny” of labels and the kvetch about “identity politics” – they have no qualms about such a label or identity, as long as its heterosexual. The only people who complain about being labelled gay are self-loathing closet cases, freshly out of the closet gaylings who still suffer from internalized homophobia and a few grad students who fell into the cult of queer theory in the 90s and have yet to be deprogrammed…Also, the tumblr loving, LGBTQAAS+_)(( special snowflakes are a different phenomenon that the non-gay gay men – if anything, they have overdosed on identity politics and keep reinventing the wheel in some bizarre identity arms race. But I think it is a stretch to infer this some sort of inexorable generational trend – these extra letters that keep multiplying like rabbits are just a tiny fraction although tumblr magnifies both their numbers and importance.