Tom said to just toss the pieces out with the trash. There were dozens of sharp shards too small to glue back together. I was pissed at the movers. This fragile plate had traveled halfway around the world safely, and now goddamn Mayflower Van Lines had destroyed it just by trucking it four miles across town.

I was determined to at least try to put the plate back together. I gathered what pieces were gatherable and laid them out on the workbench in the garage, the workbench Tom had bought us when we moved into a house together. It was already established in our relationship that I was the handy one and he was not, so the workbench was my turf, not his. We both assumed I would be the better one at repairing broken things, including this plate from the other side of the world.

In time, and never more than when our relationship began to fall apart, we learned I was not. I tried epoxy. I tried Elmer’s. I even tried the Krazy Glue I’d bought in Japan and had kept all these years. I still had the Krazy Glue but I no longer had Tadashi, my boyfriend in Japan long before I had Tom in America. Tadashi had given me the plate as a gift when I left both him and his country.

I did not tell Tom, but this plate from an earlier Japanese one would definitely have to be put together again, and for reasons that had nothing to do with him or the life we were embarking upon now in America. Tadashi had given me this plate, in our time together before Tom’s and mine, and its shattered remains were not going to be thrown out with other shattered possessions, useless things, or just things too painful to see and recall.

Tadashi and I had met in a Tokyo gay bar popular with both Japanese and foreigners. I do not recall who spoke to whom first. I don’t recall how quickly we were a couple, but it was quick. I do recall the silent decision I made to return to America, where I meant to make my career, and leave him behind without making the even the smallest effort to bring him with me. When I was young, job opportunities seemed rare but boyfriends were plentiful.

All other chores in Tom’s and my new house went unattended while I tried to make the plate whole again. I went online to learn how to fix broken pottery. I called my mother for help. I asked a guy at Home Depot. I went to the ceramics studio in the city park to see if someone there could advise me.

Tadashi took the news of my departure well, which is to say without protest. I was not the first American lover to walk out on him. The Madame Butterfly story is an old one. We were at a Tokyo party once, hosted by a wealthy white expatriate and his young Japanese boyfriend. Something made Tadashi uncomfortable from the start, and eventually I wanted to leave as well. Both of us felt guilted, if in opposite ways, by the sight of old and jowly white men accompanied by their geisha-boy paramours.

I put the pieces in a plastic garbage bag and carried them around in case someone wanted to see them before giving me advice. No one did.

Tom was older than me. He made more money than I did. But I doubt anyone thought of me as his geisha-boy.

The beautiful Japanese plate was gone and could not be restored. I put the plastic garbage bag underneath the workbench and it stayed there for years, long after Tom left me and our house as abruptly as I once had left Tadashi. If Tom were still in my life, I might have shared it with him by now, but probably not.

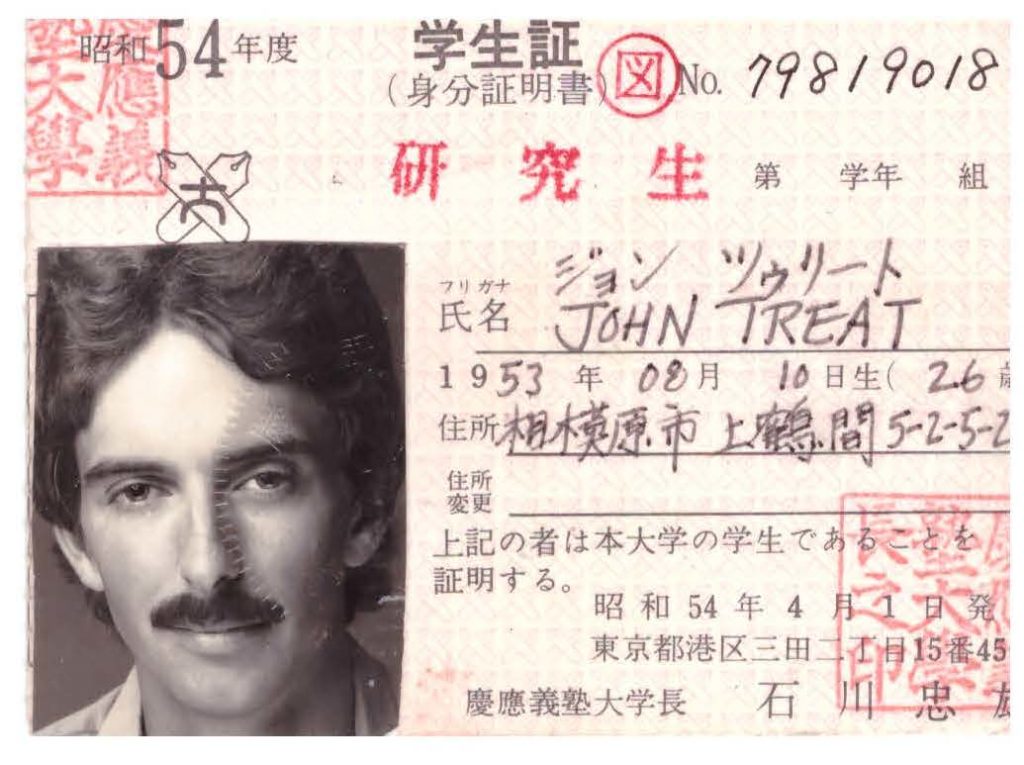

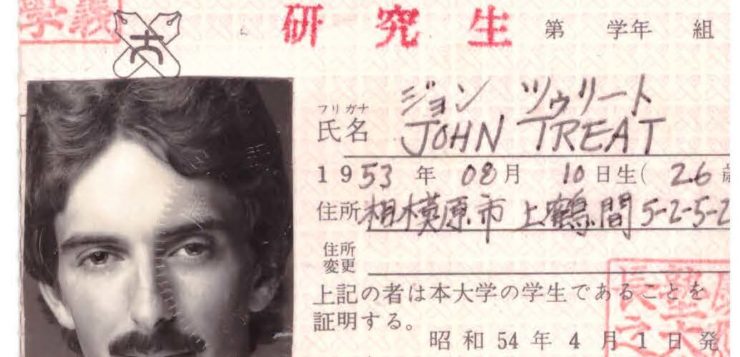

Tadashi was an artist. He had a gallery show once, that’s how good he was. He could sketch, and one day he did my portrait in pencil on a piece of fine paper. The drawing was accurate, which is, of course, why I did not like it. I thanked him and put the portrait away. It, like the plate, made it back safely to America when I left Japan. Sometimes I take it out of the box in which it remains stored and study it. So many decades later, I wish I looked today like what I did back then. I would be happy to look twenty-eight again, now that I am the age of those old and jowly white men myself.

One day I needed something heavy to weigh down one corner of a new rug I was unrolling. I used the bag with the broken plate pieces in it. They jingled and jangled as I carried the bag from the garage and into the living room. I thought: Tadashi and I haven’t spoken since I left Japan, but now here he is, and he’s talking to me. I talked back to him in equal gibberish. I imagined I was asking him to forgive me.

When I lowered the bag onto the rug’s curled corner to make it lie flat, the jingling and jangling stopped, and so did I. I might as well try to reassemble the plate again, I decided. Maybe they’ve invented a better glue since last time. Maybe the internet would have a better suggestion now. I left the bag there for a week to do its work on the rug’s edge, after which it went back to its place under the workbench, where it remains until I invent some use for it again, other than being whole.

John Whittier Treat lives in Seattle after many years in Japan, and is the author of the Lambda Prize finalist, The Rise and Fall of the Yellow House. His new novel, First Consonants, will be published this year by Jaded Ibis Press.

John Whittier Treat lives in Seattle after many years in Japan, and is the author of the Lambda Prize finalist, The Rise and Fall of the Yellow House. His new novel, First Consonants, will be published this year by Jaded Ibis Press.

Discussion1 Comment

Beautiful. Even in the broken there is value.