His beauty was hypnotic, his presence striking. My eyes went to him, there on the screen of the movie theater of my youth. His entrance into the film, sauntering up a narrow, walled walkway of the fourteenth-century Italian city, Verona, the movie’s setting, held my full attention. His features were accentuated by alluring period attire–fitted pants, and a ruffled shirt, and rounded nobleman’s cap.

I was sixteen in 1968, when I first saw him. I had remained silent in concealing my emerging and persistent-and terrifying-affection for the male form. Though I went home that afternoon enraptured by my first realized movie crush, I vigilantly guarded my feelings from others.

Meeting friends for a movie on Saturday afternoons was a ritual dating back to our elementary school years. Movies were a staple, a constant in our young lives. On a Saturday in the fall of my sixteenth year, my junior year of high school, I sat with friends in the darkened theater, transported back in time by a feature recently released to high acclaim – Director Franco Zeffirelli’s adaptation of Romeo and Juliet. Film critic Judith Crist gushed over it: “A beautiful picture sparing no lavish or literal detail. Ablaze with personal passions, the actors all lend character to the richly figured tapestry Zeffirelli has woven in brilliant color.”

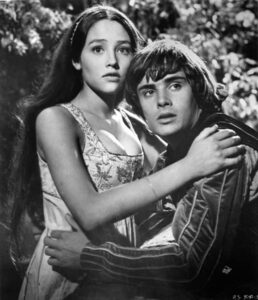

Selected for the leads were two unknowns, two teenagers who, under Zeffirelli’s watchful casting eye and adamant insistence, matched the youthful ages of the doomed lovers in Shakespeare’s play. Olivia Hussey had barely reached fifteen when she became Juliet; Leonard Whiting, the film’s Romeo, was two years older.

The newcomers were thrust into the public eye. Their acting prowess, vibrant and unspoiled, was widely applauded, though their physical virtues caught the preponderance of the glowing affirmation of moviegoers. My male peers were struck by Hussey’s features – her silken complexion, lively brown eyes, fully developed form. As we made our way home from the theater, they were vocal in their yearnings for young Juliet. I did nothing to counter their remarks, smiling and nodding in endorsement.

So, why was I so enraptured by Romeo? My affections should have been directed towards Juliet, congruent with my friends’ youthful, libidinous desires. Inwardly, though, I did not feel their pining. Outwardly, I could not share my own longings, disclosure a sure recipe for swift and adverse retribution. In 1968, in my small midwestern town, I had nothing within reach to attach my emerging feelings. I kept Romeo to myself.

The images of male homosexuals portrayed on television and film screens during my younger years are remembered for their blatant stereotypes, gay men depicted as weak, effeminate, predatory. They were mocked, held in utter contempt. Not fitting this projected image, I denied my true self, burying my feelings and hiding behind a straight façade of dates with female classmates and rugged games of street football. I had something to prove to my peers, but the real truth remained hidden away.

The jokes in the school locker room were abundant and the threats persisted. My peers’ cutting remarks warned of harsh reprisal if anyone leered at them in the wrong way. There was no worse fate than to be labeled a faggot. I tried not to look, learning the tricks of catching quick glances of developing male bodies. I could not yet put a name to what I was experiencing, nor could I risk revealing such feelings to anyone. No one would understand. I was convinced no one felt the way I did. It was a lonely, vulnerable existence.

Condemnations of homosexuality came from the pulpit of the Protestant Church on Sunday mornings, an abomination, an affliction cursed as nothing more sinful, nothing more damned. The minister’s readings came from the Bible, citing the repulsive truth of same-sex attraction. That truth could not be me, I concluded. I tried to be faithful to these biblical messages, but the preached idea of normal was not in my DNA. These suppressed damnatory feelings resurfaced time and time again, following me, haunting me.

Years passed with little resolution. As I reached adulthood, I cautiously sought out a mostly hidden community of gay men. I drove past the sole gay bar in my town many times on many weekend nights before venturing inside. Initially, interactions in the bar were rare, sometimes only minutes spent before a hasty retreat out the exit. I stayed longer with each visit. Connections were guardedly established, ranging from awkward conversations to my first, equally awkward, one-nighter.

These tentative moments eventually led to more meaningful connections beyond the bar scene, a deeper sense of friendship and community. And this awakening was cemented later by an employment opportunity— an offer to become the first paid employee with the local HIV/AIDS support organization. It was the early ‘90s, prior to the introduction of life-saving medications. We lost many good souls during my tenure, among them the gay men whose faces I recall from our shared and shielded bar scene. They, like me, had been looking for connection, seeking affirmation. They allowed me into their world. I heard stories of love and commitment, grief and regret. There were stories of mothers and fathers who had rejected their gay sons long before an AIDS diagnosis, and parents now just as detached in their sons’ final days. Some were embraced by family, but such narratives were the exception.

The gay men whose bodies and spirits had been ravaged by the disease and an often-hostile world became my backbone. Their strength and courage exhibited to the end, inspired me to remove the veil between concealment and truth. The shame evaporated, and was replaced by pride, evolving into advocacy. I co-founded a LGBTQ+ community support group, became faculty advisor for the first GSA at the college where I taught, and facilitated workshop presentations. All became an undertaking fueled by a newborn conviction.

Returning to my initial emergence into the truth, I remember a young man looking back at me from the theater screen of my youth, arousing passions repressed by the judgement of others. That afternoon – in my sixteenth year – became a defining moment in a new life. Through many cautious steps, it became a life divorced from lies. From shame. A life no longer hidden away, transformed into a life of pride, strength, and accomplishment.

Thank you, Romeo. Thank you, Leonard Whiting.

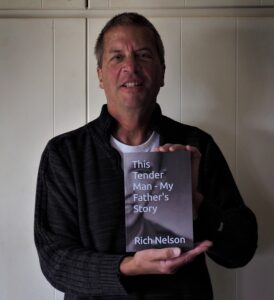

Rich Nelson is a retired college instructor and social worker. He resides in Muskegon, Michigan, along the shores of Lake Michigan. He dabbles in photography, kayaks Michigan rivers, and hikes in the plentiful dunes and woods of his native state. He is the author of the bookThis Tender Man – My Father’s Story and has contributed essays to the American Humanist Association and The Keaton Chronicle, a publication of the International Buster Keaton Society.

Rich Nelson is a retired college instructor and social worker. He resides in Muskegon, Michigan, along the shores of Lake Michigan. He dabbles in photography, kayaks Michigan rivers, and hikes in the plentiful dunes and woods of his native state. He is the author of the bookThis Tender Man – My Father’s Story and has contributed essays to the American Humanist Association and The Keaton Chronicle, a publication of the International Buster Keaton Society.