EVERY YEAR AFTER my friend Bill died by suicide, his mother and I exchanged Christmas cards. In my annual holiday letter of 1997, I announced that after years of hiding the truth even from myself, I had finally come to terms with being gay.

Just after Christmas, I moved. I had vowed to weed things out. If I was never going to read that book or wear that shirt again, I’d donate it.

I was unpacking in a hurry and slit open a box that I moved time and again without having ever opened it. Inside were all of the things that reminded me of Bill: photos, music, books, clothes, gifts he had given me. Shortly after Bill’s death, unable to deal with my guilt and sadness, I had sealed all remembrances of him away and had no intention of opening that box, either before or after the move.

I’ve lost friends to cancer and felt terrible, but I never felt guilty. I can’t cure cancer. Suicide feels different. I couldn’t have done anything to avoid the car accidents that claimed other friends’ lives. Suicide, rightly or wrongly, feels preventable. If I had listened better, been a better friend, maybe it wouldn’t have happened. Bill’s death by suicide haunted me so badly that I couldn’t bear to think about him without it causing days of depression.

When I opened that box, on top was a shirt Bill had given me. It made my heart sink. I hadn’t planned to deal with this box now or ever, but the shirt wouldn’t release my stare.

I remembered my self-imposed dictum to get rid of anything I would never wear again. But the shirt was one of my last tangible reminders of Bill. I couldn’t give it away. I should just seal the box and deal with it another time. I should just throw it out. I was spinning in a mental circle as I faced what I had avoided for years.

After at least an hour, maybe two, I grew tired of my stupid indecision. I needed to go pick up my mail from my P.O. Box before they closed. I decided, screw it, it’s just a shirt. Put it on and get the mail.

In the mail was a padded envelope with Bill’s mother’s return address. In it was a gold ring. I recognized it immediately as Bill’s. He treasured that ring. It had been made for him by his great-uncle who since had died. After one trip to England to visit his mother’s family, Bill came back heartbroken. He had been helping his mother’s brother work in the garden and apparently the ring had slipped off his wet finger. They searched the garden with no luck.

With Bill’s ring was a note from his mother saying her brother had been working in his garden and found the ring. She received the ring the same day she got my coming out letter. She wanted me to have the ring by proxy for Bill. She was happy that I’d finally found the self-acceptance that Bill never had.

Suddenly everything fell into place. The real reason Bill had killed himself. I sat in the car and cried until I calmed down enough to drive.

Bill’s death had always been a scab for me. Not an open wound, but a barely-healed scab I was afraid to go anywhere near. I had a hard time remembering the good times with Bill since the ending was so horrible. Now, I felt like he had forgiven me (if there was ever anything to forgive) and I knew I could think of him again without going to the bad places.

When I got home, I called a friend of Bill’s and asked how soon I could see him. He and Bill had gone to high school together and lived together in Belgium for a year. I figured if anyone knew if Bill was secretly gay, he would. He said that even in high school, Bill’s friends had assured him that it was okay to come out, but Bill always vehemently denied being gay.

I asked why he thought Bill was gay and he ran through a list of stereotypical gay interests, the way he dressed, held his cigarette. I had attributed the mannerisms to being half-English and spending so much time in Europe. (There is the old joke: Is he gay? No, just European.) The friend also said he wondered about Bill at times saying things about me that crossed the line from friendship to crush. In my mind I replayed many of the moments I’d had with Bill and they made so much more sense now.

I wrote to his mother and told her that far more than his ring, she had given me back Bill. I could think of him now and not be sad.

I was able to unpack the rest of the box of Bill’s things. It seemed beyond coincidence that for the first time since he died, I was wearing his shirt, while I was holding his ring. If I needed a final endorsement that I was doing the right thing by choosing to be happy for the first time in my life, this was it. It put one more piece of my old life behind me, to be happy out of the closet. I wish Bill could have found the same happiness.

I’ve had many people ask about the ring. Sometimes just handing my credit card to a store clerk, she has grabbed my hand to look at the ring. Some people seemed to sense the magic in it and asked if it had a story. Once, I was telling the story to the clerk then I realized a line was forming at the register. I apologized to the other customers and stepped aside, but they all protested, “No, this is good. Go on. Finish the story. Please tell us the rest.” And I told them the story of Bill and the ring.

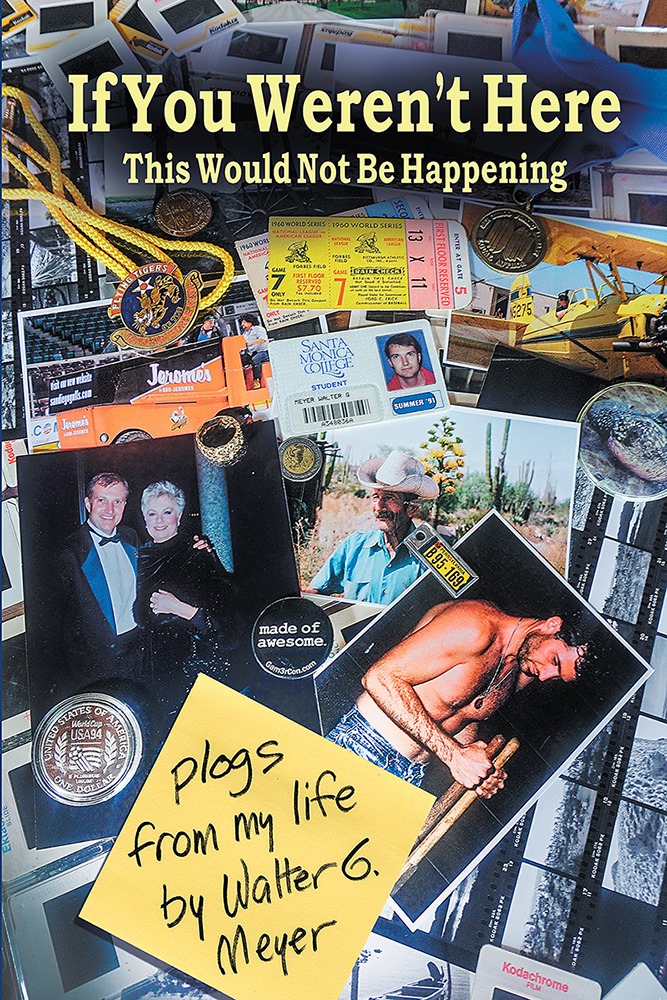

This story has been abridged and adapted from If You Weren’t Here, This Would Not Be Happening: Plogs from My Life.

Walter G. Meyer is the author of the gay-themed novel Rounding Third and has written for Out, Advocate, and other LGBT periodicals and has also written on LGBT topics for the mainstream media.

Walter G. Meyer is the author of the gay-themed novel Rounding Third and has written for Out, Advocate, and other LGBT periodicals and has also written on LGBT topics for the mainstream media.